Chevron Looking for More LNG Buyers as Gorgon Ramps Up

Chevron Corp. expects to begin shipping natural gas next week from the massive Gorgon Project offshore Western Australia to buyers that are more concerned about reliability of supply than chasing short-term price cycles, executives said Tuesday.

CEO John Watson outlined capital spending plans and reviewed major projects in the queue during the annual analyst meeting, including the now completed Gorgon liquefied natural gas (LNG) project.

Gorgon, considered one of the largest gas export facilities ever built, is designed to export up to 15.6 million metric tons/year of LNG from Barrow Island; some contracts have been secured with Asia Pacific buyers (seeDaily GPI, Jan. 29; Jan. 19). A carbon dioxide injection project and a domestic gas plant with the capacity to supply up to 300 terajoules/day to Western Australia also are part of the project.

“We expect legacy assets such as Gorgon will drive long-term growth and create shareholder value for decades to come,” Watson said. “The long-term fundamentals for LNG are attractive, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region, and this is a significant milestone for all involved.”

Chevron operates and is majority stakeholder (47.3%) with joint venture partners ExxonMobil Corp. (25%), Royal Dutch Shell plc (25%), Osaka Gas (1.25%), Tokyo Gas (1%) and Chubu Electric Power (0.417%).

By 2020, Chevron has its sights set on becoming a major LNG supplier. Along with Gorgon, it also is spearheading the Wheatstone LNG export project in Australia, which should ramp up shipments in 2017.

More than 80% of Chevron’s Australian subsidiary equity LNG from Gorgon and Wheatstone is covered through sales/purchase agreements, or heads of agreements (HOA), said Executive Vice President Mike Wirth.

However, “on LNG sales, we are still in the market for contracts,” he said. “The initial tranche on 80% is with really good buyers that have been in the market for decades…We have a broader suite of people we are talking to today, HOAs announced…It is a little bit different today,” as some customers want shorter-term contracts. “People have different ideas now how they’d like to structure pricing. We still have oil-indexed [contracts] but also other hybrids and other [types] of pricing that are more prevalent today” and want to execute contracts “that we think are good for us and that buyers find acceptable…Or we will sell into the spot market…”

Wirth said he realizes that some potential customers want to see Gorgon established as a “reliable supplier,” which would then help firm up more contracts. He said “more news is expected in the coming quarters as we progress negotiations.”

The contracts now in place are “long-term oil indexed…We are relatively well covered for the ramp-up period,” Wirth said. More contracts should be finalized as more trains are online. The second Gorgon train is scheduled to start up between April and June.

“We have good buyers who understand these markets,” Wirth said. “They are not prone to chase short-term prices…They are looking for reliability of supply.”

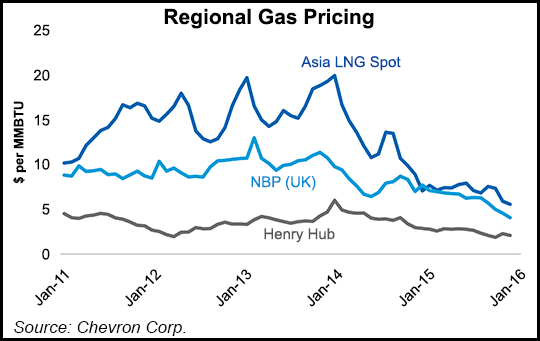

Until prices collapsed, Chevron, like its peers had concentrated most of its exploration and development efforts on long-term, expensive endeavors like LNG export facilities and the deepwater. Those high-end ideas seemed viable, price-wise, at the start of the decade, Watson said.

“When we were starting up this big queue of projects, we knew there was a downside in the process, but we didn’t expect to see prices drop to where they are today,” he said. “The reality is, the LNG market is different from what we expected, and we don’t expect to see many more projects moving in the near-term. As we complete the ones we have under construction, we will live within our means in this period.”

That doesn’t mean that all investments are off the table. For instance, the Tengiz Field being developed in Kazakhstan by Chevron and partners “is not premised on $40 oil. It needs a higher price.” But development continues because “once it’s online, it’s a good project.”

The same goes for the longer-term Gulf of Mexico deepwater projects. Chevron has delayed some promising moneymakers but it still plans to drill “three or so” exploration wells this year, which “are not cycled at $40 oil either, but we are making some moves that are counter cyclical…

“We are making choices,” said the CEO. “We have to bring costs down, but we are not abandoning other asset classes. We will need them.”

At the top of the list in the U.S. onshore in the Permian Basin, where Chevron has a two million net legacy leasehold. Commodity prices have forced a course correction, Watson said.

Last year, Chevron’s global oil and gas production rose 2% from 2014, but from its shale/tight sands portfolio, output jumped 33%. The Permian offers the best “shorter cycle opportunity,” said the CEO.

“We will see higher spending in the Permian as we increase rigs over time. As we continue to make progress in other shales, we’ll see growth as well. By the middle of the next decade, 20-25% of production could be in short-cycle shale and tight activity…”

One of the Permian’s drawing cards for Chevron is its “royalty advantage,” upstream chief Jay Johnson told analysts. About 85% of the legacy leasehold has no or low royalties associated with it with an estimated 9 billion boe of resources. An estimated 1,300 drilling locations across the Permian make a 10% return at $40/bbl crude oil, Johnson said. Another 4,000 locations turn a profit at $50, while 5,500 can make money at $60. And that’s only an an assessment of about one-third of the portfolio, he added.

Chevron plans to drill 175 wells this year using seven operated rigs and nine other rigs. By 2020, up to 350,000 b/d could be pumped from the massive basin, versus 125,000 b/d today.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |