Shale Daily | E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Montney Shale: Winning Combo of Reserves and Markets

While activity slows in almost all the shale plays across North America, growth is reaching warp speed in Canada’s Montney tight sands formation, which looks to be developing into the western version of the Marcellus Shale.

In the last few years numerous major pipeline and development projects have been announced, while the largest of all, a C$36 billion Asian-backed chain of investments awaits regulatory approval. The investment would include LNG export terminal construction on the British Columbia coast along with drilling and pipeline construction in the nearby Montney.

The Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency (CEAA) is expected to approve the proposal for Pacific NorthWest LNG, the Asian entry in the lineup of liquefied natural gas (LNG) export schemes proposed for the BC coast,

If CEAA avoids imposing costly conditions, the project’s leader — Progress Energy, a Calgary subsidiary of Malaysian state-owned Petronas — and partners Sinopec, Japex, Indian Oil Corp. and Petroleum Brunei are committed to starting big spending. The group has been a pioneer of global-scale gas supply development from scratch.

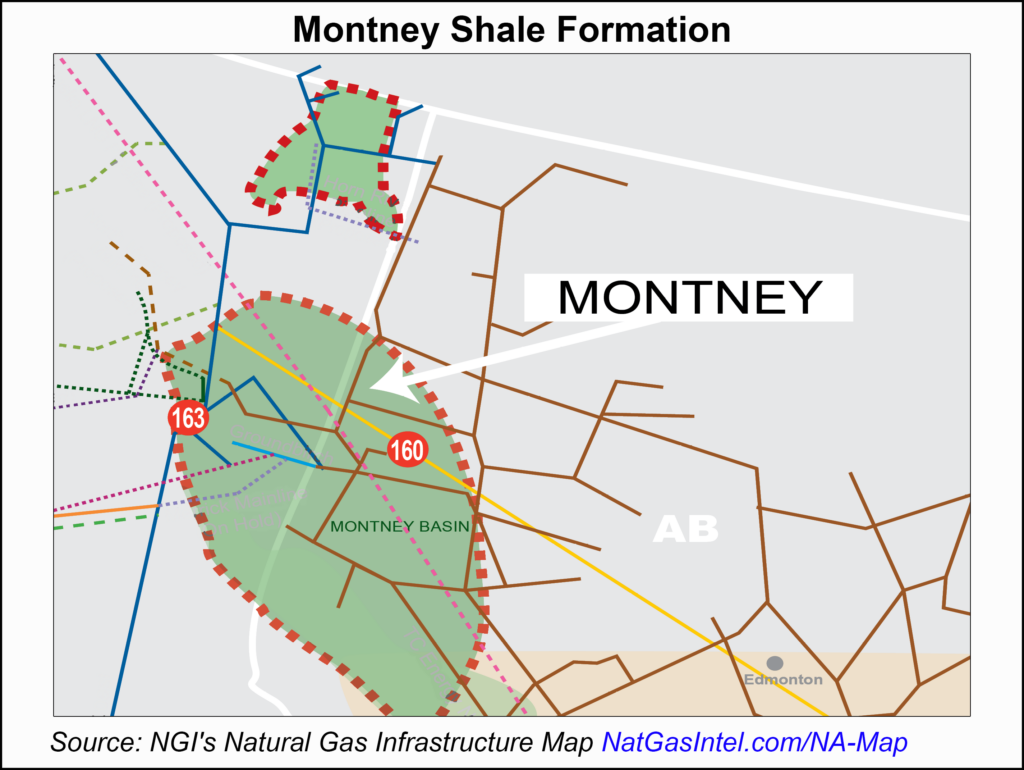

What they will be scratching in Canada is a 52,000 square mile geological layer with 60- to 180-feet productive zones that straddles the BC-Alberta border. A conservative assessment in 2013 by various provincial and Canadian federal regulatory bodies came up with astronomical numbers for “marketable” parts of the Montney resources: 449 Tcf of gas, 14.5 billion barrels of gas liquids, and 1.1 billion barrels of oil. More than half of the gas and liquids are in BC. (see Shale Daily, Aug. 15, 2015)

The most recent conservative estimate of recoverable resources from the Marcellus Shale is 141 Tcf.

Industry, financial and government forecasters expect the Montney to keep on cooking as Canada’s most active drilling area even if the Asian export project to the west waits for oil prices to rise again, lifting LNG in overseas energy value indexes.

That’s because to the east the area supplies the nation’s largest and fastest-growing industrial gas user: Alberta thermal oil sands complexes.Counting associated steam heat and power cogeneration stations, the bitumen extraction and synthetic crude upgrading operations use an average 1 Mcf of gas per barrel of output. An industry survey by the National Energy Board (NEB) reports that 800,000 b/d of new production capacity is still under construction. As of 2024 the current annual provincial reserves report by the Alberta Energy Regulator forecasts oil sands plus cogeneration gas use will hit 5 Bcf/d.

Bitumen belt plants have 50- to 60-year lifespans and the corporate giants that dominate the multibillion-dollar investments continue to follow strategies that look beyond current market gyrations. None have cut delivery contracts that drive Kinder Morgan Canada’s plan to triple capacity to 890,000 b/d on the Trans Mountain Pipeline from Edmonton to tanker docks in Vancouver, the project reported as the NEB began hearing final arguments on the construction application shortly before the end of 2015.

Bitumen development gives gas producers a double incentive. In addition to buying fuel, oil sands projects create demand for light liquid byproducts used as “diluent” for pipeline transport. The thinner is up to 30% of the shipments.

The Montney formation stands out as the current primary gas and liquids warehouse for evolving LNG and oil sands markets. Current projects that tap and connect the deposit to markets include:

How big can the Canada’s most accessible and best known natural gas and liquid byproducts formation become? Canadian industry analysts compare the Florida-sized Montney formation to the Marcellus shale colossus in the eastern United States.

The Montney geology differs as tightly compressed sand- and siltstone. But production employs northern adaptations of the horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing used in American shale formations. Early development has followed the U.S. pattern of improving output and falling costs as experience is gained with the technology, observe reports by agencies including the NEB and the Canadian Energy Research Institute.

A 2013 assessment by the AER, NEB, BC Oil and Gas Commission and B.C. Ministry of Natural Gas Development came up with astronomical numbers for “marketable” parts of the Montney resources: 449 Tcf of gas, 14.5 billion barrels of gas liquids, and 1.1 billion barrels of oil. More than half of the gas and liquids are in BC.

The earth sciences appraisal deliberately erred on the conservative side. The agencies emphasized that the forecast uses only limited experience gained with a minority of the deposit since industry began using the advanced well technology in 2005. The estimates of marketable supplies are only about 10% of the natural resources rated as physically “in place” in the formation for industry to tackle with improving knowledge and techniques.

On both sides of the BC-Alberta boundary, the Montney stands out as the only Canadian “tight” or shale formation where there is enough experience and information to attempt commercial evaluation. The layer underlies a century old forest products, agricultural, mining and oil and gas frontier.

The Montney region is laced with roads, bridges and public and industrial services connecting a network of settlements and three sizeable centers: Grande Prairie in Alberta, and Dawson Creek and Fort St. John in BC Southern legs of the Alaska Highway create a transportation artery through the remotest northern reaches of the drilling zones.

The service network is expected to improve as a result of a C$8-billion (US$5.8-billion) dam project that provincial government-owned BC Hydro is beginning to build on the Peace River near Fort St. John, titled Site C. Construction is moving ahead after fending off aboriginal, environmental and landowner protest lawsuits. The verdicts keep open a legal path for development that makes serious efforts to consult communities, respect claims, settle disputes, and accept approval conditions of minimizing and repairing damage.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |