Big Oil in Need of Big Overhaul to Sustain Growth, Says Report

Big Oil has been a big bust for the past several years, and without a major overhaul, sustaining efforts in stagnant natural gas and oil environment are going to be a challenge, according to Morgan Stanley Research and the Boston Consulting Group (BCG).

The two firms combined their global research efforts to jointly address how and why the majors should shake up their operations. The report issued Tuesday, “Big Oil: Toughen it Out, Or Business Model Reboot?” concentrates on seven integrated oil and gas companies based in the United States and Europe: BP plc, Chevron Corp., Eni SpA, ExxonMobil Corp., Royal Dutch Shell plc, Statoil ASA and Total SA. For research purposes, 63 smaller exploration and production (E&P) companies were used for some of the comparisons.

Declines in overall earnings and reserves growth among the majors have been documented, and criticized, for years, and perhaps are more relevant today as the forward curve suggests that oil prices won’t rebound above $72 for the next three years. “The urgency to improve is greater than ever,” said Martun Rats of Morgan Stanley and BCG’s Maurice Berns, who oversaw the 32-page report.

Exploration success by the majors “has been particularly disappointing in recent years,” despite increasing E&P spending. For instance, Wood Mackenzie Ltd. “estimates that the value created by pure exploration has been close to zero for the majors in aggregate over the last five years.”

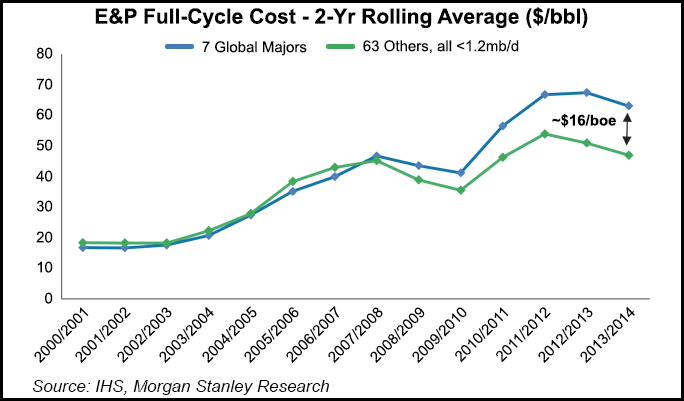

Beginning around 2008, the majors began to experience more cost inflation than the rest of the industry, particularly among the smaller E&Ps. Costs accelerated after 2010, when the U.S. unconventional revolution began to spread, and many of the smaller E&Ps came into the cost curve to the left of the majors.

“In the cost environment of 2013/14, the full-cycle cost of the majors was $63/boe, which compares with $47/boe for the 63 smaller companies, a $16/boe difference. This is partly offset by high price realizations: during those two years, the majors generated upstream revenues of $65/boe compared to $61/boe for the other 63. Still, this left the majors with full-cycle FCF of $2/boe versus $9/boe for the ‘group of 63’.

“In a commodity industry where profitability is primarily a function of relative cost positions, these differences are large.” The majors were found to be at a cost disadvantage among the 63 E&Ps for taxes, as well as development costs and exploration costs:

“During 2013/14, 55% of the majors’ reserve additions came from new discoveries, with the remaining 45% coming from upwards revisions of the reserves in existing fields,” noted the authors. “For the ‘group of 63’, 90% of reserve additions came from discoveries, and only 10% from revisions.”

Because of its volatile nature, exploration has to be measured and compared over a several years. Still, with capital increasingly constrained, rethink exploration efforts and find other ways to add resources, noted the authors. For example, they suggested using more discovered resource opportunities or DROs, which are known reserves that can be added to the portfolio not via the drillbit but through business development and negotiations with government. As well, the price downturns often provide opportunities to make acquisitions, both for assets and entire companies.

Even before the collapse in commodity prices, the returns on capital for Big Oil had come under pressure, and often, organic free cash flow (FCF) wasn’t enough to fund dividends.

“Many are now questioning the sustainability of the integrated business model,” noted the authors. And in fact, some majors already have taken that route, splitting their refining arms from exploration and production, including ConocoPhillips and Marathon Oil Corp. (see Daily GPI, July 5, 2011; Jan. 14, 2011).

Operating models also need to evolve, researchers found.

“The model of the broad generalist is under pressure, and specialization is on the rise,” said the report. “An upstream world that is fragmenting into multiple niche oil and gas sources no longer suits a ‘one size fits all’ model. Big Oil must better connect a portfolio of focused businesses in a network that harnesses their collective scale — rather than trammeling them with complexity and overhead.”

As well, the culture has to change. “Big Oil still lacks a truly cost-conscious culture,” said researchers. “The focus has long been skewed toward safety, volumes and reliability. Without some rebalance, efficiency programs are likely to fail to deliver their potential — and Big Oil can no longer afford a period of incremental cost adjustment. The challenges are far greater, and 2015 may present the best opportunity for some firms to shape a competitive future.”

There is a clear precedent for the evolution, noted the authors. In the aftermath of the 1986 oil price collapse, the majors “dramatically lowered cost and improved efficiency, which allowed strong earnings and share performance in subsequent years, despite an extended period of oil price weakness.”Since early 2012, however, it’s been a different story, even with rising oil prices. Over the past three years, the European-based majors have lagged the overall market by 40%, the sharpest underperformance of any three-year period since 1973.”

A revamp of operating practices, if done successfully, would be worth the effort as “the size of the prize” is considerable.

“We conclude that the days of Big Oil are by no means over,” said the authors. “Big Oil’s unique blend of technical capability, financial strength, risk capacity and global reach will remain relevant in the years ahead — and will not be entirely displaced by either service companies or smaller independents. But the model must evolve.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |