U.S. NatGas Pipeline Capacity A Match For EPA Clean Power Plan, ICF Says

The nation’s expanding natural gas pipeline system will be up to the task for the evolving power generation needs that result from implementing federal mandates under the proposed Clean Power Plan (CPP), according to an analysis.

The Advanced Energy Economy (AEE) Institute contracted with ICF International to assess the potential impacts of U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) proposed CPP on required gas pipeline capacity. The CPP, still in draft form, would establish state-by-state carbon emissions rate targets to reduce by 2030 U.S. power sector emissions by 30% below 2005 levels (see Daily GPI, May 22). A federal court in early June tossed a lawsuit by 14 states and several coal companies that attempted to block the plan before it is finalized by EPA (see Daily GPI, June 9).

AEE undertook the analysis because some stakeholders, including the North American Electric Reliability Corp., have raised concerns that states would have to rely on increased gas-fired generation for CPP compliance, which might stress natural gas pipeline capacity and ultimately affect system reliability. The ICF research used three scenarios to assess CPP’s potential impact:

ICF researchers found that even with low gas prices, no significant increase in gas pipelines would be required if CPP were implemented. Compliance “even under an unlikely ‘stress test’ scenario of unexpectedly high gas usage would only modestly increase the gas infrastructure needs, in the range of 3% to 7%,” the report said.

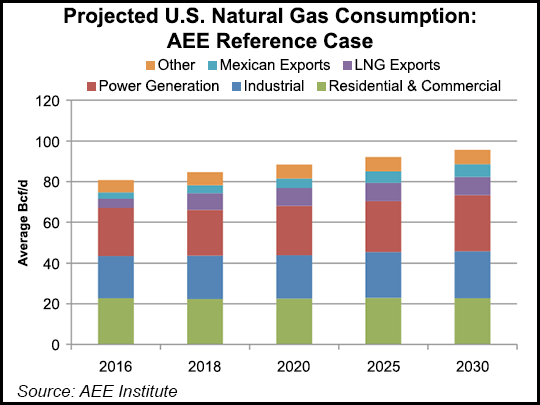

The big reason for the lack of stress on U.S. gas infrastructure is the increasing number of pipeline projects already being planned to expand capacity over the next three to five years. Power sector gas consumption in the reference case grows steadily, in part on more than 40 GW of projected coal unit retirements between 2016 and 2020. Demand growth already is projected to be met increasingly by increased use of existing gas-fired units and new gas-fired capacity, with gas the dominant fuel source for generation through 2030.

“The largest projected driver of gas demand growth through 2020 in the reference case is exports” to Mexico and from liquefied natural gas terminals, with more than 10 Bcf/d of incremental pipeline takeaway capacity recently completed or under construction from Texas and Arizona to Mexico. In addition, more than 40 announced pipeline capacity projects — either new, flow reversals or a combination — are proposed for Appalachia’s Marcellus and Utica shales, driven by growth in production. The total proposed pipeline capacity out of the Marcellus/Utica exceeds 34 Bcf/d by 2020, ICF estimated.

“These ?planned projects are sufficient to meet both the anticipated growth in gas demand in the reference case (that is, demand growth not related to the CPP) as well as the incremental demand in the CPP cases,” the researchers said.

Less stress on capacity also would follow assumed increases in energy efficiencies, which would reduce power load growth relative to the reference case.

“Because electric load growth is lower, power sector gas demand in the Northeast and West regions is actually lower in the CPP case in 2030 than in the reference case, and only slightly higher than the…low gas price case.”

In addition, the Midwest and South power sector gas consumption is projected to increase in both CPP cases, but these areas are “relatively close to incremental gas supplies,” principally the Marcellus and Utica shales.

“The proximity of the incremental gas demand from Marcellus/Utica to the Midwest and South on existing pipelines reduces the amount of new pipeline and capital expenditures required,” ICF said.

With or without CPP, the amount of investment in new gas pipeline capacity over the past decade suggests that projected investments in the future “are well within the capabilities of the industry…Furthermore, this analysis does not capture the evolution of certain technologies (e.g., gas demand response) and electricity grid operational techniques,” such as ISO New England’s pay for performance rules, “which are changing and will continue to change the relationship between gas demand and infrastructure needs.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |