Barnett Shale Water Contaminants Point to Need for More Study, Say Researchers

Samples taken from drinking water sources within or near active natural gas wells in the Barnett Shale contain metals and chemical compounds at levels exceeding federal limits, according to a peer reviewed study that expands on findings made in 2013.

Researchers from the University of Texas at Arlington (UTA) published their findings in the American Chemical Society scientific journal Environmental Science & Technology. Natural gas drilling was not singled out as the source of contamination, but the findings should be “an impetus for further monitoring and analysis of groundwater quality,” the co-authors said.

The newly published work is a followup to a report in 2013 regarding sampling of 100 water wells, which indicated there were elevated levels of potential contaminants such as arsenic and selenium in groundwater near Barnett gas sites (see Shale Daily, July 30, 2013).

In the new study, groundwater samples were analyzed from water wells that draw mostly (83%) from the Trinity and Woodbine aquifers, which are above the Barnett. Researchers conducted analytical chemical tests on 550 samples from 350 water wells serving residences, 59 from agricultural water wells and 141 from municipal/public water supply wells that service communities in the Dallas-Fort Worth area.

Ten different metals found in the samples exceeded U.S. Environmental Protection Agency maximum levels. Also detected in 381 of 550 samples were 19 different chemical compounds, including BTEX — benzene, toluene, ethyl benzene and xylene. In addition, levels exceeding the federal maximum for methanol and ethanol were found. In the 2013 report, researchers did not detect BTEX.

“These data do not necessarily identify unconventional oil and gas (UOG) activities as the source of contamination; however, they do provide a strong impetus for further monitoring and analysis of groundwater quality in this region as many of the compounds we detected are known to be associated with UOG techniques,” researchers said.

Researchers “can’t definitely say” that gas drilling affected the water “but we can’t rule out that it was not the culprit,” said co-author Zacariah Hildenbrand. He owns Inform Environmental LLC, which helped coordinate the study and conduct the sample collection. “It is more likely that it has had an effect on water quality.”

Researchers are on “the ground floor…trying to understand” the source of the contamination, he said. “We’re not trying to shut down drilling.”

The Barnett extends across about 5,000 square miles. The samples, taken without prior knowledge of drilling activity, were from 13 counties: Montague, Wise, Parker, Hood, Tarrant, Somervell, Johnson, Hill, Ellis, Dallas, Denton, Collin and Cooke. Sites were selected on the basis of well owner participation and the researchers’ ability to collect untreated water representing the underlying aquifers.

UTA’s Kevin Schug, Shimadzu Distinguished Professor of Analytical Chemistry, led the research.

“I hope our data can serve as a springboard for studies that use detailed chemical signatures to pinpoint the impact of various aspects of unconventional drilling processes on groundwater quality,” he said. That way changes in drilling processes could be made if they are needed.

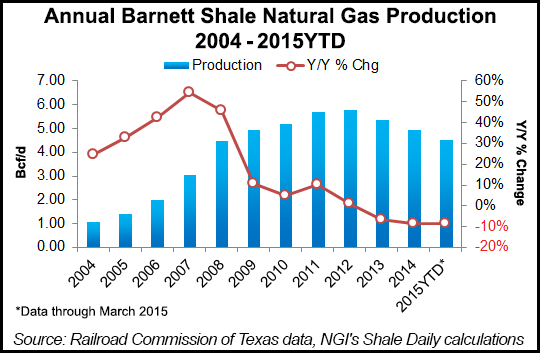

The Barnett, considered the granddaddy of the U.S. shales, is home to more than 200,000 unconventional wells. Since the gas boom began in the Dallas-Fort Worth area almost a decade ago, many have questioned whether potentially harmful chemicals used during various phases of gas extraction and related activities could make their way into the area’s aquifers.

Also contributing to the new study were researchers from University of North Texas, University of Houston, Tarleton State University and SWCA Environmental Consultants.

The study was criticized by some industry groups, including the Barnett Shale Energy Education Council. Executive Director Ed Ireland noted that some of the chemical levels reported could be from agricultural sources, not from drilling. “You need to do a more comprehensive study” to link the groundwater to drilling sources, he said.

Energy In Depth also disputed the findings, noting that the researchers admitted they could not link contamination to unconventional drilling.

However, Earthworks spokesman Alan Septoff said, “I would argue that 550 wells over many square miles meets any reasonable definition of ‘widespread.’ It is not pollution from one well but it is pollution from many wells.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |