Opponent of Trans-Pecos Pipeline to Mexico Vows to Fight

A Texan opposed to the Trans-Pecos Pipeline, which would carry 1.4 Bcf/d of natural gas from the Eagle Ford Shale to Mexico, believes developers will ultimately get their project — but not without a fight.

“In stopping the pipeline, I have truthfully very little hope,” Coyne Gibson told NGI. “In making it as difficult and expensive for Energy Transfer Partners [ETP] and the consortium as is humanly possible, I will do everything I can.”

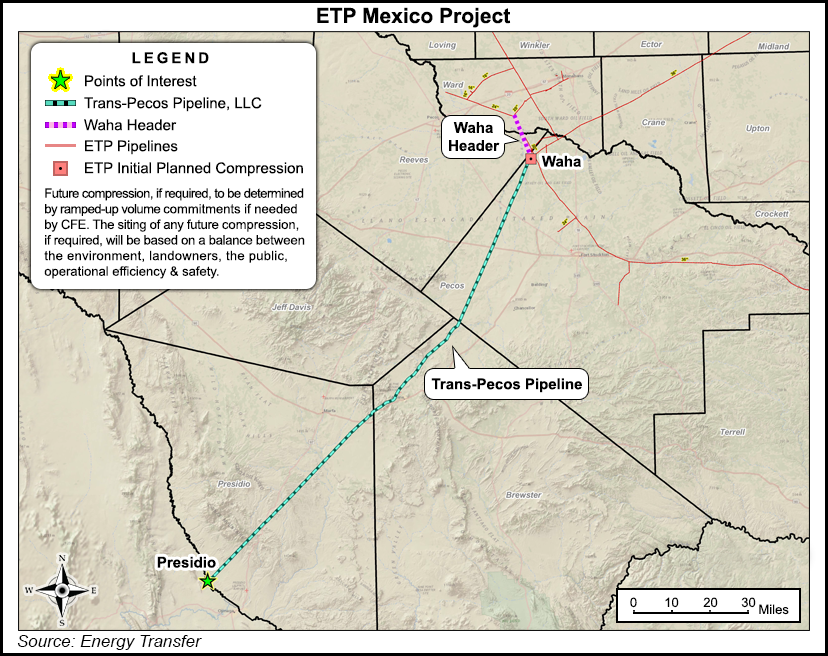

However, pipe and equipment are showing up for the job now. Trans-Pecos, proposed by ETP and Mexico’s Carso in response to a solicitation from Mexico’s federal electricity commission, would be 42 inches in diameter and run 143 miles from the Waha Hub outside Fort Stockton, TX, in northern Pecos County.

The intrastate pipeline, which has been permitted by the Railroad Commission of Texas, would deliver some gas to Texas towns on its way to the international boundary at the Rio Grande. The rest would be carried through a Mexican pipeline connecting at the border to supply power plants. Construction is to begin by the first quarter for completion about a year later by the end of the first quarter of 2017.

It’s the region the pipeline will traverse that has angered Gibson and other activists, some with the Big Bend Conservation Alliance (BBCA), which has a website opposing the project.

A retired engineer, technology entrepreneur, environmentalist and stargazer, Gibson worked on some pipeline projects during the 1970s, he says. He now is a research engineer and scientist associate at the McDonald Observatory of The University of Texas at Austin. He speaks only for himself, he says, when he speaks out against the pipeline, although he does volunteer with the BBCA.

Texas’ Big Bend National Park, covering more than 800,000 acres, is the country’s largest protected area of Chihuahuan Desert. Overall, the desert is the largest in North America, the majority of it lying south of the international border. The park gets its name from a bend in the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo, which forms the boundary between the United States and Mexico. It’s the state’s last wild frontier, has a sensitive ecology and, so far, only one natural gas pipeline: a six-inch diameter distribution line serving area towns, Gibson says.

That has raised the ire of some in Fort Stockton, Presidio and Alpine, where ETP has held public education events, Gibson says. He faulted the company for scheduling the Presidio meeting at 9:30 a.m. on a weekday. Attendance was about 100 over a three-hour period, he says. The meetings “were handled pretty poorly is the general consensus of opinion of those who attended out here.”

Gibson opposes the pipeline for several reasons. When his concerns were relayed to ETP, company spokeswoman Vicki Granado provided a two-page fact sheet on the project and said in an email that “there has been both false and unsubstantiated information put forth by individuals that do not have detailed knowledge of the project or the mechanics of how pipeline systems operate.”

Area fire and emergency personnel would be unable to cope with a pipeline rupture and fire, Gibson worries. “We’re in really rugged territory,” he says. “We’re also an all-volunteer force…minimally equipped…under-served, just because of the low population density out here, so when we have to fight something like a wild land fire, it’s a major problem.”

Granado did not respond when asked if ETP would do anything to bolster the capabilities of emergency responders. The project’s fact sheet, however, says, “Our top priority is to provide safe and reliable transportation of natural gas” and describes weld inspections and hydrostatic testing during construction. “All safety valves along the mainline will be remotely controlled and monitored for pressure at all times — 24 hours a day/seven days a week,” it says.

Gibson also worries about construction impacts on the environment. ETP plans to have 50-foot easements along the pipeline route with an additional 75 feet of easement during construction. “They’ll do the best they can to restore it,” Gibson concedes, “but the issue we have here is we’re a relatively fragile ecosystem; it’s arid, dry. When you disturb the ground out here, what happens is we see invasive species take over instead of what the native cover was.”

And then there’s dark sky tourism, not least of which that stimulated by the area’s McDonald Observatory. Light pollution won’t be a problem during construction, Gibson has been told, because there won’t be construction activities at night, he says.

“Any safety lighting required along the route will comply with all outdoor lighting ordinances,” ETP says.

Another worry for Gibson is that he’s heard — despite statements from ETP to the contrary — that there could be a compressor station placed mid-route along the pipeline. “Initial plans do not include compression beyond the point of origination, resulting in no noise or odors along the route,” ETP says in its fact sheet. Gibson says he’s heard otherwise.

Talk around a local recreational vehicle park by workers said to be engaged for the project is that they’re working on a compressor station downstream of the head of Tres-Pecos, Gibson says. The engineer in him doesn’t believe the project will work with compression only at the beginning of the pipeline as the company has proposed.

“The suspicion is that there needs to be a mid-route compressor station somewhere, which is most likely in the Alpine region,” Gibson says. “We’ve had representatives of ETP tell us no, but we’re hearing rumors…There are people at an RV park in Alpine that are telling us that they’re working on a compressor station.”

Granado did not respond to a question about siting of compressor stations beyond what is said in the fact sheet.

“There are things like that that just don’t add up,” Gibson says of the compressor question.

Granado also did not respond when asked how many area landowners have signed easements for the project. “ETP is telling us that they’ve already obtained agreements from 50% of the landowners in the route,” Gibson says. “We have no means of verifying that number.” He says that surveys by BBCA have yet to identify a landowner who has granted an easement or is considering doing so.

Some of what Gibson fears about the pipeline — issues related to construction in particular — will be temporary. Other things can be mitigated by, for instance, compliance by the pipeline operator with International Dark Sky Association guidelines for lighting, environmental restoration and other measures.

“We would like to see this thing classified as a private pipeline — which in reality is what it is — and that would at least take away the company’s access to eminent domain condemnation,” Gibson says. “That would give the landowners who aren’t interested a fear-free way of simply saying ‘no.’

“To the extent that I will tell you what we’re doing, there is a head-on challenge at the Railroad Commission relative to the permit itself, the T4 [permit],” Gibson says. A “flanking strategy” involves challenging the pipeline on an environmental basis, and then there’s lobbying and networking with area politicians and tax commissioners.

“The toughest part of all this is the company representatives have come out here telling us that they want to be a good neighbor. Pretty much at every turn there are things that are happening that tell us something vastly different,” Gibson says, citing laydown yards for pipe and equipment that are next to residential areas, “which is just astonishing.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |