Marcellus | E&P | Haynesville Shale | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Utica Shale

Both Haynesville, Appalachia Seen as Marginal Sources of U.S. NatGas Production

The Haynesville Shale may be competing with Marcellus/Utica shale gas in the not-too-distant future, lifted by its solid reserves, infrastructure and its proximity to liquefied natural gas (LNG) export facilities, according to research by NGI’s Shale Daily.

Appalachia “is certainly here to stay,” but there are several reasons the Haynesville is drawing renewed interest by exploration and production companies, said Patrick Rau, NGI director of strategy and research. He discussed the outlook for the two big gas basins during a webinar on Tuesday. Areplay is available.

The Northeast basin is “a major structural part of the U.S. natural gas production industry going forward.” However, the trajectory of its gas production growth should slow over the next few years. Meanwhile, with “basin-on-basin competition from the Haynesville, we expect that natural gas production growth rate from the Appalachia will start to slow more toward the national average as we get to the end of the decade.

“Said differently, we expect that both the Appalachia and the Haynesville will be the marginal sources of production going forward. And since the Henry Hub is a proxy for Haynesville pricing, we think that Appalachia and Henry Hub will both serve as the price of marginal production in the years ahead.”

A big reason that the Haynesville will give Appalachia a run for its money is its location, which straddles a broad swath of North Louisiana and East Texas. That puts it close to four prospective LNG export terminals planned along the Texas and Louisiana coasts.

“We believe the Haynesville is particularly well positioned to take advantage of LNG exports from the United States at the end of this decade,” Rau said. “By the end of 2020, we think that LNG exports could account for up to 10% of U.S. demand…”

Rau noted that BG Group plc, a big-time LNG exporter, has some big-time opportunities in the Haynesville. The company is merging with LNG expert Royal Dutch Shell plc (see Shale Daily, April 8).

BG has a 50-50 joint venture in the Haynesville with explorer Exco Resources Inc. (see Shale Daily, Aug. 8, 2013a) BG also has a “major presence in at least two of the export facilities” planned for the Gulf Coast: the Sabine Pass LNG Terminal and Lake Charles Exports LLC (see Shale Daily, Aug. 8, 2013b; Daily GPI, May 15, 2013).

“I certainly can’t speak for what BG plans to do, but given what they do for a living and their big presence there, it wouldn’t surprise me at all if they start to ramp up their presence in the next couple of years.”

The Haynesville, which was just roaring along until natural gas prices first slumped, leasehold positions became held by production and Appalachia began lighting up the screen, still has a lot of life left in it. Among other things, it’s scalable, Rau said.

The Haynesville currently is producing about 7 Bcf/d, but at its peak “it was more like 11 Bcf/d…There are a lot of wells still to be drilled there,” anywhere from 35,000-50,000 wells.

The Haynesville also “has plenty of takeaway capacity. It’s already dry gas, so it doesn’t need to be processed before it’s shipped overseas.”

Operators also have more room to recomplete and add more fractures (fracks) to Haynesville drilling locations — things that would cost less than drilling a new well. Chesapeake Energy Corp., the first to make the Haynesville a household name, sees more value in the Haynesville today than in the Marcellus (see Shale Daily, Feb. 25). Encana Corp. last year reported that recompletions in the Haynesville were recovering 1-2 MMcf/d at a cost of about $1 million per well (see Shale Daily,Aug. 22, 2014).

“We think the Haynesville has potential for quite a few more recompletions of wells than does the Marcellus,” Rau said. “Certain companies now are starting to experience some success by going back and refracking some of the wells that were originally drilled in the Haynesville to hold acreage there back in 2008, ’09, ’10, back when technology hadn’t advanced quite as much as it has today.

“There have been a lot more wells drilled in the Marcellus with the newer technology. So we think there’s an opportunity to recomplete wells in the Haynesville a little bit more than in the Marcellus.”

The chances that Appalachia may overtake the Henry Hub as the national pricing point are “virtually nil,” Rau said. Some pundits have suggested that overwhelming gas production has made Appalachia the price proxy. However, for all its growth, Appalachia produces about 20% of the natural gas in the country compared to the 40% contribution from the Gulf Coast region, which encompasses all of Texas and Louisiana and the Gulf of Mexico.

And with Henry Hub already positioned to handle future U.S. LNG activity, it’s “likely to be a pricing point for international pricing by the end of the decade.”

A big handicap for Appalachia is that it remains “on the “lower end of pricing.” The Appalachia is the one area that’s consistently been the lowest priced area of gas in the U.S. According to forward curves, it should continue to be on the lower end of pricing of natural gas…

“To say that the Appalachia is representative of the entire country from a production or a pricing standpoint, it certainly isn’t.”

The crux of the argument about whether Appalachia has become the price-setter centers around the big switch in where gas is produced in the United States. Appalachian gas output grew from less than 6% of domestic production in 2006 to more than 20% in 2014. The Gulf of Mexico (GOM) in the 1990s represented around 25% of total U.S. gas production; today it’s about 5%.

That turnaround “certainly legitimizes the question,” about Appalachia market strength, Rau said. To determine the answer, Rau and his team combined Gulf Coast gas production — all of Texas and Louisiana — with GOM gas output “because I still believe that the Henry Hub serves as a reasonable proxy for the price of production for the entire area. There is a basis differential between northern Louisiana [and Texas] and the Henry Hub, but the emergence of…the Haynesville Shale, the Barnett Shale, the Eagle Ford and the Permian is what’s kept the Gulf Coast relevant.

“But even when you add in all those increases in unconventional sources, Appalachia still is growing and the Gulf Coast still has declined in terms of total production.” Combined Gulf Coast/GOM gas output has fallen from about 50% of gas output in 2006 to about 40% in 2014.

The analysts used spot market trading data taken from NGI’s bidweek survey since 2006. Appalachia in 2006 represented a little more than 6% of total traded volumes. It was up to 26% last year. The combined Gulf Coast/GOM area has fallen from about 45% of reported volumes in 2006 to around 30% in 2014.

With the unconventional revolution and the resulting increase in 3P reserves — proved, probable and possible — a lot of the risk factor that the United States is going to run out of gas has been priced out of the market, Rau said.

Appalachia has overtaken Henry in one big respect: it is the marginal production area in the United States.

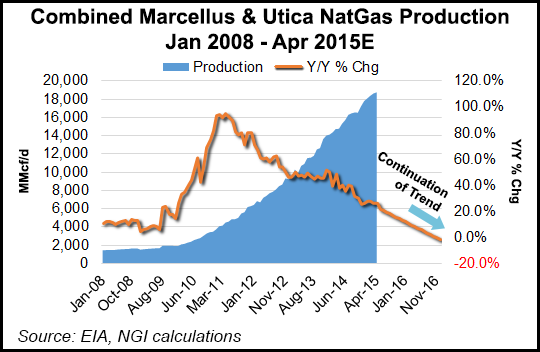

“I think, clearly, the answer to that is yes, it has,” Rau said. “Marcellus/Utica gas production has grown by very, very high rates lately. It’s the fastest growth that we’ve seen in this country, so it is the marginal production area.”

However, Appalachia production growth is declining — not turning negative, just slowing down. “Large numbers problems” loom for the Northeast, Rau said. “The faster and more that absolute production in the Marcellus and Utica grows, simply the more difficult it’s going to be to grow it year over year.”

Year-over-year gas production growth actually began declining in the Northeast basin in 2011. Extending the Appalachia production trend line out, Rau determined that negative year/year production growth may occur after 2016.

But “this is a very simplistic argument,” he said. Appalachia gas output won’t be at a loss after 2016. “We don’t believe that. We expect it to continue to grow. But it’s not going to continue to grow at the historical rate that it has.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |