Regulatory | NGI All News Access

BP Argues U.S. Operations Threatened by Excess Macondo Fines

Federal officials urged the court overseeing the Macondo well blowout litigation to slam BP plc and Anadarko Petroleum Corp. with substantial Clean Water Act (CWA) fines to send a message to the entire exploration industry.

Subsidiary BP Exploration & Production Co. (BPXP) was majority owner and operator of the doomed well in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico, while Anadarko was a 10% stakeholder. Neither company is entitled to a significant reduction of its mitigation activities following the April 2010 explosion and massive oil spill, the federal government told U.S. District Court Judge Carl Barbier. The case in the Eastern District of Louisiana is In re: Oil Spill by the Oil Rig “Deepwater Horizon” in the Gulf of Mexico on April 20, 2010, No. 2:10-md-02179.

In early 2012, Barbier ruled that BPXP and Anadarko were liable for civil penalties under the CWA (see Daily GPI, Feb. 24, 2012). At that time he also ruled that BP and Anadarko were the responsible parties under the Oil Pollution Act for oil that flowed from beneath the surface of the water.

Barbier, who is presiding over a three-phase trial, has ruled that BPXP was grossly negligent for its actions before the blowout but determined that BPXP’s response efforts following the blowout were not negligent. Using the amount of oil calculated to have been spilled, minus some cleaned up by BP, in January Barbier said BPXP should be fined up to $13.7 billion under the CWA, far less than had been predicted (see Daily GPI, Jan. 16). The U.S. Justice Department is arguing for the maximum for BPXP and said Anadarko should pay less than a $3.5 billion maximum but more than $1 billion paid by Deepwater Horizon owner Transocean Ltd.

“Given the defendants’ large size and extensive resources, very high penalties for BPXP and Anadarko are warranted — for BPXP, near the statutory maximum — otherwise the penalties will amount to a write off for the cost of drilling in the Gulf,” Justice argued. The Justice Department claims that BPXP had $25 billion in assets as of March 2014, with leases and reserves that could be worth up to $18 billion in new production after 2015. Prosecutors noted that $3.5 billion already is set aside to pay CWA fines.

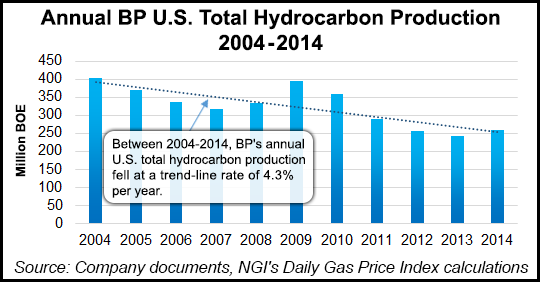

In its 287-page rebuttal, BPXP argued that a multi-billion fine could negatively impact the company. The producer also argues that its response minimized and mitigated the spill’s effect. BPXP already has paid billions for spill-related liabilities. BPXP argued that the London-based parent isn’t legally obligated to pay the debts of subsidiaries and would “pierce the corporate veil.” Also, penalties above $2.3 billion could threaten the solvency of the U.S. business, even if crude prices jumped to $100/bbl, the brief argued.

“Imposing a penalty on BPXP anywhere near the amount suggested by the United States would disincentivize future operators from engaging in a robust and sustained response like that mounted by BPXP,” BP spokesman Geoff Morrell said. “Furthermore, a CWA penalty above the low end of the statutory range would threaten BPXP’s solvency and have a significant negative impact on BPXP’s expenditures in the Gulf region.”

If it were to face the stiffest penalties BPXP may be required to eliminate up to 2,300 U.S. jobs, cut annual spending by $5 billion and reduce Gulf Coast operations, the company claimed.

“The United States incorrectly suggest that BPXP’s past borrowing from affiliates allows one to assume future funding to pay” the penalties, the brief stated. The circumstances were “materially different” when other BP affiliates backed BPXP’s efforts to respond to the spill and $14 billion in costs were incurred “at a blistering pace at a critical time.”

Meanwhile, June 8 has been established as the deadline to submit a claim for economic and property damages (E&PD) related to Macondo. The E&PD settlement class includes “people, businesses, other entities and properties in the states of Louisiana, Alabama and Mississippi, and certain counties in Texas and Florida.” The EP&D website provides detailed descriptions and maps of the included geographic locations to assist class members determine whether they are a part of the settlement class.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |