NGI Archives | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Winter 2014-2015 May Land Another Punch, Forecaster Says

Rumors of the demise of winter 2014-2015 are premature, according to Michael Schlacter, chief meteorologist at Weather 2000.

“People should not underestimate what is possible in late March, the first half of April, with regards to snow and ice and heating degree days [HDD],” Schlacter told NGI.

“Sometimes people, being tired of a long winter or frustrated by oversupply and prices not reacting, write off the very end of the season, but based on our climate research and a seasonal shift, and based on this particular winter season showing a lot of ferocity still in Canada, with delivery mechanisms in place, there’s no reason why the next two or three weeks couldn’t produce the kind of weather that’s on par with what you might see the last week of November and the first two weeks of December. Other than in the deep South, April is a full fledged heating degree day month.”

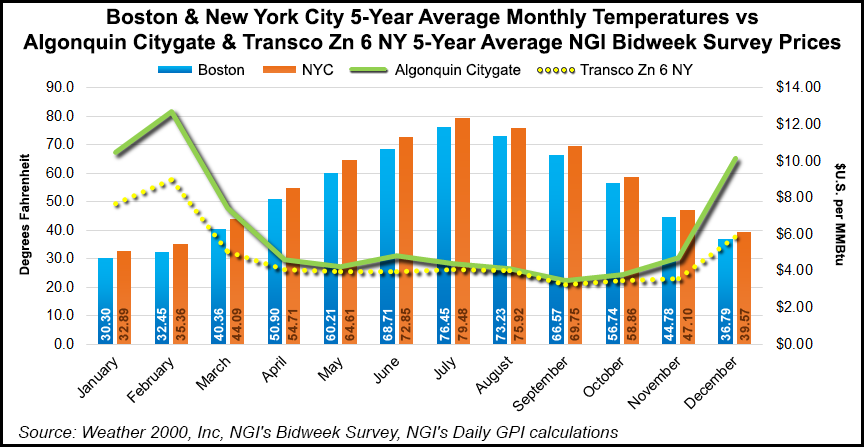

Forecasters at Weather Services International (WSI) this week said they expect temperatures will average cooler than normal across the Northeast in April, keeping the pedal on energy consumption in some of the nation’s major population centers (see Daily GPI, March 23). But the WSI forecasters also expect warmer-than-normal temperatures to dominate the region in May and June.

One commonly held belief — that winter 2013-2014 was colder than this winter — is incorrect, Schlacter said. A brief spell of relatively warm weather in December distorted the image of what has actually been an “extremely cold” winter, he said.

“Factually, as the winter is measured by most of the weather industry, the five months November 1 through March 31 were fundamentally much colder for a lot of key hubs than last winter was. And for the Midwest, while it fell a little bit shy of last winter — which was record — if you start the clock on January 1, we’re actually beating last winter for places like Chicago and Detroit and Cincinnati and St. Louis and some of the midwestern hubs…

“Last winter was very cold and harsh for all five months, and then this winter took that up a notch and went from very cold and harsh to extremely cold and harsh, relative to monthly normals for November, January, February and March, but it put back some into the pot for December.”

It may be time for weather observers in the energy industry and elsewhere to reconsider some long-held assumptions about temperature forecasting, including the timing and length of seasons, the impact of El Nino events and more, according to Schlacter.

“Our long-term climate research has been showing that our seasons have been shifting deeper into the calendar year, and what that means is that the old time paradigm that people had, that ‘oh, maybe we’ll get some excitement in November, and then December is kind of the make or break month, and then once we get to New Year’s we’re at the halfway point, and if it’s not a super exciting winter, then it’s basically destined to be a dud’…

“That might have been the case way back in the day with some of the climate patterns, [but] our research is showing that especially in the past decade, really our winters have become January through March, and there is even occasional bleed over into the first half of April, with occasional snow or ice storms and some impactful HDD tallies anywhere from the Midwest to the Northeast. The reason why that’s important is that if people view the winter as being in the fifth inning by Christmas, then they’re going to be shocked to learn that they’re really only in the second or third inning by Christmas, and there’s a lot yet to come.”

A decade’s worth of research also indicates that shoulder seasons have been shrinking, Schlacter said.

“Our autumns and our springs aren’t dealing with this placid, 90-day energy neutral period that may have been the case back in the day,” he said. “Because of the extended winter season, and because of sometimes early onset summer conditions, sometimes it’s only a month…March is a full-fledged, intense winter month, and in extreme seasons like this year, it can bleed into the first half of April and, especially if there’s a little drought or a little high pressure ridging, especially for the South, you could start getting summer impacts in late May or early June. So that shoulder season has shrunk…it has greatly been reduced over the last 10 years.”

Even some basic concepts and analogs like El Nino events — warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures in the central Pacific Ocean near the equator — staples of many short-term forecasts, may not be the best indicators of seasonal trends, he said. The El Nino events of the 1990s were different than those of the past several years.

“El Nino has been misforecast. Basically, it’s been a flop. It really hasn’t materialized the last five winter seasons in a row…This past winter, a major El Nino was forecast and what transpired was a neutral event that perhaps in the recent couple of months may have reached bare minimum government standards of what a very, very bare minimum weak El Nino is classified at, which is based on sea surface temperature anomalies in the equatorial Pacific. But essentially it was a bust again.”

The long-awaited El Nino event arrived last month, but unlike some of its predecessors, it is likely to remain weak and exert little influence on global weather and climate, according to a recent forecast from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (see Daily GPI, March 6).

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |