NGI Archives | NGI All News Access

Huge Natural Gas Hydrate Reserves In Cold Storage — For Now

Natural gas hydrates hold the potential to contribute to future energy systems worldwide within the next 10 to 20 years, according to an arm of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE).

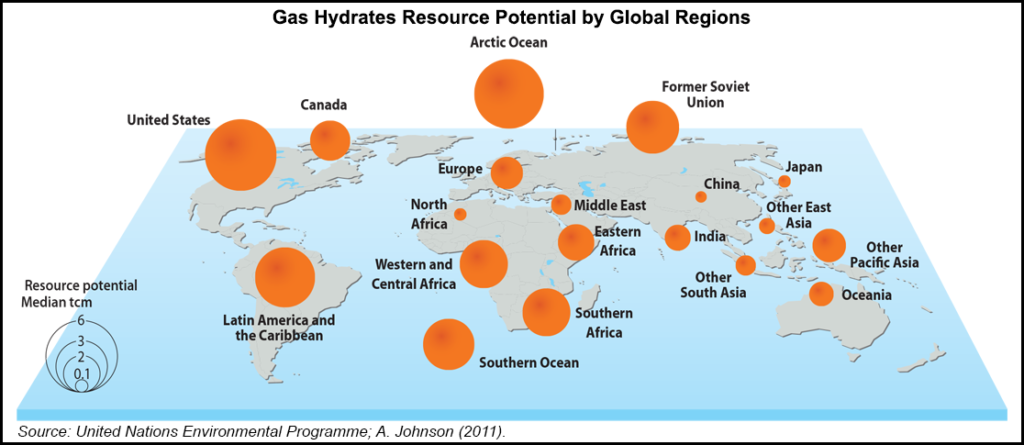

Researchers for the National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL), housed within the Office of Fossil Energy, contributed to a new report that outlines prospects for gas hydrates as a worldwide energy resource. The team participated as part of the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP), which resulted in a two-volume assessment, “Frozen Heat: A Global Outlook on Methane Hydrates.”

Gas hydrates are combinations of methane and water that form naturally in geologic environments where there are low temperatures and relatively high pressures. Most marine gas hydrate deposits found so far have been in continental margin and slope sediments, often with deposits of other hydrocarbons, such as oil and natural gas.

“Gas hydrates generally occur in relatively inaccessible polar and marine environments, which is why they have not been extensively studied until recently,” said UNEP Executive Director Achim Steiner. “Research about naturally occurring gas hydrates has increased markedly over the past two decades, however, and understanding about where hydrates occur and how they might be exploited is growing rapidly. Japan has recently tested offshore production of natural gas from a hydrate reservoir located more than 1,300 meters below the sea’s surface, and other countries are also actively exploring production potentials.”

The global inventory of gas hydrates “appears to be very large,” the researchers said. “Recent estimates of the total amount of methane contained in the world’s gas hydrates range from 1,500 to 15,000 gigatonnes of carbon. At standard temperature and pressure, this represents 3,000-30,000 Tcm (trillion cubic meters) or 0.1 to 1 million Tcf, and has an energy equivalent of 0.1-1.1 million exajoules.”

Within the global inventory, a smaller subset of gas hydrate is “technically recoverable or suitable for production using existing extraction technologies. At present, the widespread but low concentrations of gas hydrates in fine-grained marine sediments are not seen as candidates for economic development. However, concentrated gas hydrates occur in marine and permafrost sands in some locations, particularly the Alaska North Slope, northwestern Canada, the Gulf of Mexico, and offshore Japan. These deposits have physical properties and reservoir settings that appear conducive to production using adaptations of conventional hydrocarbon recovery methods.”

In North America’s Barkley Canyon offshore Vancouver Island and in the Gulf of Mexico (GOM), methane seeps have formed “massive mounds of gas hydrate…that lie exposed on the seafloor, often covered by thin drapes of sediment.” Gas hydrates have been confirmed on Alaska’s North Slope (see Daily GPI, Feb. 21, 2007). In the GOM, more than 6,000 Tcf is estimated to occur within the most promising gas hydrate accumulations, based on recent estimates by the U.S. Department of Interior’s Bureau of Offshore Energy Management (BOEM). The BOEM estimates were supported by a 2009 scientific drilling program conducted by DOE (see Daily GPI, May 15, 2013; April 1, 2010; May 15, 2009).

The UNEP report “stresses the need for a stronger foundation in science to assess mitigation of any environmental impact from development,” according to NETL. “The report’s findings also complement NETL’s current priorities for hydrate science and technology development, which include establishing a long-term field testing site in Alaska and conducting further scientific evaluation and sampling of gas hydrates in the U.S. offshore.”

Substantial investments would be required to realize hydrates’ potential, the researchers noted. In addition, “methane is still a fossil fuel that emits greenhouse gases…The key for each geographic region is to determine where gas hydrates fit in a larger development framework and whether the extraction, processing and marketing of natural gas from gas hydrates provides a net advance in achieving its goals. With commercial production of methane from gas hydrates still years away, there is time for regions and nations to make those determinations.”

UNEP and contributors to the research intend for the research “to enable sound policy discourse and choices that take into account a number of important perspectives.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |