Marcellus | E&P | NGI All News Access

With Wolf’s Inauguration, Questions Loom For Pennsylvania NatGas Industry

When Democrat Tom Wolf is inaugurated as Pennsylvania’s 47th governor Tuesday, it could mark a new, if uncertain, beginning for the state’s natural gas producers.

The political landscape is poised for a serious shift with the arrival of Wolf and a new administration. The Pennsylvania that gave rise to the modern shale gas era with the drilling of Range Resources Corp.’s Renz 1 well in Washington County in 2004 is not the same. And Wolf, sources unanimously agree, is not likely to be the same kind of governor as the two before him that oversaw the Marcellus Shale’s breakneck evolution.

Wolf will enter office at a time when much of the nation’s politics, including Pennsylvania’s, have been gripped by polarization. The state’s Independent Fiscal Office is forecasting a $1.85 billion budget shortfall for fiscal year 2015-2016, with the public, Democrats and Republicans torn about how to resolve its cost drivers and tired of the one-time fixes that have led to similar holes in the past.

Despite a rich history of natural resource extraction in Pennsylvania, observers say that never before has there been a juggernaut such as the Marcellus Shale in the state’s backyard. The political shift and the challenges both the gas industry and Wolf will face come mainly with the question of whether the play and its leaders can be a golden goose for the state. Many are wondering if the industry will be singled out to solve the budget crisis and related issues.

“We’ve seen three governors, counting Wolf, that have had a substantial role since the emergence of the Marcellus Shale play, or at least since it became attainable. [Gov.-elect Wolf] is the first since [Democrat Ed Rendell], who served during the emergence of the play,” said Christopher Borick, director of the Muhlenberg College Institute of Public Opinion in Allentown, PA. “[Rendell] didn’t go very hard for an extraction tax. He didn’t necessarily say he didn’t want one, but he let it play out. [Gov. Tom Corbett] was directly opposed to it. This will be the first governor that has pledged, in a very-high profile way, to support and call for an extraction tax.

“He’s not going to be the same governor as Corbett was for the industry,” Borick added. “He is, in many ways, the front-runner on this — the public face of this push.”

He doesn’t necessarily have a clear field, however. Wolf took the governor’s office with more than 50% of the vote, but state Republicans also increased their majorities in both chambers of the general assembly. With a 35-seat majority in the House and a 10-seat majority in the Senate, Wolf will likely have to compromise if he wants to win a severance tax, sources said.

Wolf, 65, a businessman from York County, campaigned aggressively on a platform to reform the natural gas industry, primarily with a pledge to enact a 5% severance tax on production that he says could raise up to $1 billion annually (see Shale Daily, Nov. 5, 2014; May 21, 2014). He’s also indicated that he’s opposed to natural gas development on state-owned land, in favor of a more transparent industry and stronger regulations.

Despite repeated attempts, Wolf’s transition team did not answer questions for this story. Considered a pragmatist by many, Wolf has also praised the natural gas industry’s economic benefits. Educated at Dartmouth University, the University of London and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he ultimately earned a doctorate, Wolf knows a thing or two about doing business.

After buying his family business, the Wolf Organization Inc., he helped transform it into one of the nation’s largest suppliers of kitchen cabinets and specialty building products.

“I don’t think he’s one you might call an adversary of shale gas either,” Borick said. “He’s never called for a moratorium. He’s praised the broad effects on the state economy, but he’s very much in line with Pennsylvania attitudes about shale gas — he generally supports it. Polls have shown that voters believe the industry has had a net benefit, that oil and gas development is a good thing overall. But they also want it taxed, and Wolf has really settled in with public opinion on these kinds of issues.”

The Big Question

For years now, Republican- and Democratic-controlled legislatures in the state have failed to agree on a severance tax (see Shale Daily, Jan. 28, 2014). It’s become increasingly difficult to ignore the prospect, though.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, natural gas production in the Marcellus Shale has soared, going from less than 1.7 Bcf/d in 2010 to more than 16 Bcf/d this month. In 2013, the state produced 3.3 Tcf of natural gas and it likely surpassed that total last year, with operators reporting 2 Tcf through the first six months of 2014 (see Shale Daily, Sept. 19, 2014; Feb. 20, 2014).

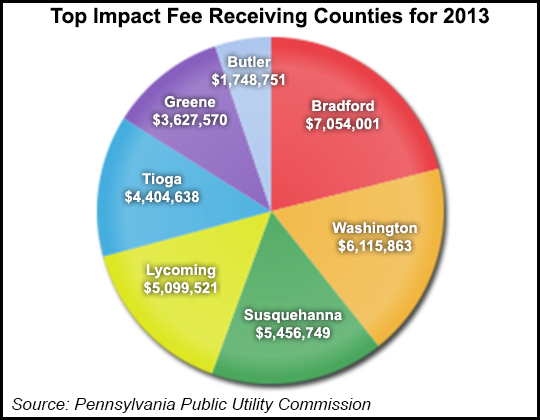

The fate of any severance tax legislation, however, also depends on the state’s impact fee, which was a compromise with a governor who had taken the Tea Party’s “no new taxes” pledge, and public and legislative forces which wanted to see a government benefit from the burgeoning industry. Passed in 2012, it charges a flat rate for all unconventional wells drilled in the state no matter how much gas is produced (see Shale Daily, Feb. 15, 2012). The fee has generated more than $630 million in revenue since its inception, with the funds distributed to counties, municipalities and state agencies (see Shale Daily, April 4, 2014)

“You have a legislature who was rightfully proud of the impact fee,” said Patrick Henderson, Corbett’s energy executive and deputy chief of staff. “There are many influential legislators who are tired of having endured for the last six to nine months claims that they have not regulated the industry, or called upon it to contribute to the Commonwealth. I think they’d point to the impact fee and the environmental standards in this state to say indeed we have.

“The way the law is written now, if you enact a severance tax, the impact fee goes away. There are 67 counties that receive annual checks from the Commonwealth for the impact fee,” Henderson continued. “Forty counties that are located in the heart of the Marcellus Shale or have some development going on within their borders receive separate checks. That’s an awful lot of township supervisors, borough officials and leaders that rely on that money.”

Borick said the impact fee will be a “major problem” for Wolf’s severance tax proposal. Other sources said it will boil down to politics, noting that any severance tax would have to include some sort of allocation to townships and counties if the impact fee is replaced.

“At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter what you call it. The point is, at the local level, the revenue allows local elected officials to address and deal with the impacts of oil and gas development,” said David Sanko, executive director of the Pennsylvania State Association of Township Supervisors (PSATS), which represents 1,454 townships, where most natural gas is produced in the state. “Frankly, if that money wasn’t there, it would result in property tax increases. No one went off and said ”this is Christmas’ and went on a wild spending spree when that law passed. In many instances, it went into a capital reserve fund,” to deal with the costs associated with drilling.

Sanko said his organization is pleased with the funding that the impact fee currently provides for its members. He added that state lawmakers often look to local elected officials for input on legislative affairs and said PSATS is ready to work with them on preserving the impact fee or ensuring that communities across the state continue to receive a significant portion of revenue generated through the natural gas industry.

Old Problems

Budget shortfalls are nothing new for Pennsylvania. In recent history, gaps going back to the 1990s have led to some of the state’s largest tax increases. Some of the cost drivers and arguments for filling those voids have been consistent, such as state pension reform and Republicans’ insistence that Pennsylvania’s state-run wine and spirits stores should be done away with and privatized.

According to the state budget office, Pennsylvania’s pension system for state workers and public school employees has an unfunded liability of $47 billion. Republicans also argue that privatizing the state liquor stores could bring in about $1.5 billion. Pundits have suggested that Wolf stands a better chance of enacting a severance tax through a compromise on one or both of these issues.

“No one wants to increase taxes anywhere else, and if you’re not going to do that, a lot of attention will have to be given to pensions,” Borick said. “Ultimately, where the bargain comes and how much Wolf will give on pensions or liquor privatization depends on how much Republicans give on a shale gas tax, The bargain will come in the interest of both sides because they have to solve this.”

The state House of Representatives is where Wolf is expected to face the most resistance on a severance tax. A spokesman for Speaker of the House Mike Turzai didn’t dismiss a compromise, but said more thought needs to be given to the other issues.

“When you’re talking about the budget, you need to look at all the cost drivers, like the public pension system, look at the revenues that can be generated,” said Turzai spokesman Stephen Miskin. “We think that privatization has an ability to bring in more than a billion dollars up front and it can help us grow revenue into the future by saving the $240 million in lost sales and taxes from border bleed.”

An argument also exists that the state’s natural gas producers already pay their fair share with the impact fee, the corporate net income tax and a capital stock and franchise tax. Producers have paid more than $2 billion in taxes alone since development began. As a result, industry representatives have said there can be no compromise on a severance tax.

“While we appreciate Mr. Wolf’s support of the state’s growing natural gas industry — which is generating huge amounts of revenue, boosting manufacturing and creating thousands of good jobs, especially for small businesses and our region’s labor and building trades — differences certainly exist as it relates to policies that would harm job growth and discourage investment in the Commonwealth,” said Marcellus Shale Coalition President Dave Spigelmyer.

The Pennsylvania Budget and Policy Center (PBPC), a nonpartisan think-tank, released a report over the summer that found even as gas production has boomed, corporate net income tax payments by drilling companies are falling. The report found that natural gas producers paid just $10.3 million in corporate taxes in 2013, compared to about $19 million in 2008.

“If you look at it over time — the taxes paid by drillers in this state — there hasn’t been a big increase in things like corporate and sales tax payments since drilling began, compared to before,” said PBPC Research Director Mike Wood. “There hasn’t been this bonanza of tax dollars that’s been talked about. From our standpoint, if you look at what drillers receive in federal incentives to promote development, they get a lot of tax breaks that flow down to individual states that affect their taxable income.”

Wood said the PBPC backs Wolf’s severance tax proposal. He suggested that it is one of the only viable ways to solve both the state’s immediate and long-term budget woes. He added that privatizing the state’s liquor stores is the kind of one-time fix that Pennsylvania has relied on too much in the past. He also said pension reform won’t solve the state’s near-term revenue problems.

Beyond the Budget

Questions remain about how Wolf will deal with other thorny energy-related issues. In May, Corbett lifted a moratorium on subsurface leases in state-owned forests that was enacted by Rendell (see Shale Daily, May 23, 2014). In doing so, he hoped to raise $95 million for the state. That order was challenged by an environmental group, but a commonwealth court judge recently upheld it and noted that future leasing decisions are ultimately up to the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR) (see Shale Daily, Jan. 8) .

The state has conducted just three lease sales in state forests, in 2008 and in 2010, but Wolf has said he’s not in favor of further development.

“An interesting thing about this court ruling is that if DCNR does decide to lease, it will not be up to the governor’s office,” Henderson said. “I’ve said we’ve never been in the business of issuing or directing leases. That works both ways from a legal perspective. If a governor says ‘no leases, I don’t like them,’ it works the other way too. The decision is with DCNR, not the governor. As a practical matter, DCNR will have a secretary that’s philosophically aligned with the governor.

“I’m not suggesting DCNR would go ahead with leases when Wolf takes office, but as a legal matter, the governor can not come in and say leasing is barred.”

Wolf has appointed Cindy Dunn to lead DCNR (see Shale Daily, Jan. 14). Dunn has served as the president of the environmental advocacy group PennFuture since 2013, an organization that’s been highly critical of the state’s oil and gas industry. Henderson went further to say if the $95 million included in Corbett’s 2014-2015 budget is not generated, the state will have to find another way to plug that gap.

Earlier this month, a group of a state and national environmental groups, including PennFuture, called for Wolf to address methane emissions from Marcellus natural gas operations, imploring him to adopt “leading-edge” practices to prevent pollution and further protect the environment. Following an announcement from the Obama administration to curb oil and gas emissions by 45% over the next decade, PennFuture officials said that effort misses the mark because it includes only new sources and provides little mitigation for existing ones (see Shale Daily, Jan. 14). Wolf has acknowledged in the past that the state needs to get “clean air and clean water regulations” that could help further prevent methane leaks from happening.

Also complicating matters for the industry is a series of legal challenges that have cropped up in at least six counties across the state. After a landmark court decision in 2013 that struck down parts of Act 13 and gave municipalities more power to change or enforce zoning laws, drilling opponents have stepped forward to challenge development in residential and agricultural zones (see Shale Daily, Dec. 20, 2013). The areas are home to much of the state’s Marcellus Shale wells, and opponents argue that well pads are violating their environmental rights and threatening their safety (see Shale Daily, Dec. 1, 2014).

The Wolf administration could intervene to support or oppose those challenges.

“Ultimately, the fallout from the Act 13 court decision is going to continue,” Henderson said. “I believe there are a lot of proponents of that decision, who are, quite frankly, out there raising a lot of mischief. We in the Corbett administration are cognizant of this stuff. There have also been occasions in the past where the Commonwealth has entered briefs in courts on the compatibility of oil and gas activity in agricultural zones, where we have weighed in on why we think they’re compatible.”

Many agree that it’s difficult to make predictions about what will happen in the next four years. One thing is clear, though, Wolf will have to act fast on some of his key policy proposals, such as a severance tax, which is widely expected to be included in his first budget due in March.

“There’s a number of things that are going to happen because I know legislators have a number of things they want to look at,” Wood said. “I think, at least traditionally, the first budget is when big things happen.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |