E&P | NGI All News Access | Regulatory

Gunnison Sage Grouse Listing May Impact E&Ps in Utah, Colorado

The Obama administration is weighing whether to list as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) the Gunnison sage grouse, which could pose problems for oil and natural gas development in parts of Utah and Colorado. The Interior Department’s Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) is set to make the decision Wednesday.

Colorado officials said they are expecting that a notification from Interior will be made Wednesday, followed by publication of the details in the Federal Register a few days later. A listing likely will prompt legal challenges from the states and local governments, state officials indicated.

Under the ESA, a species is listed as “threatened” if it is likely to become an endangered species within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range. It can take years to be removed from a threatened listing by the FWS. The most perilous listing of “endangered” is given if a species is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range. It may take decades to be removed from the endangered list.

Since being proposed last year for listing, estimates on the annual cost of conservation of the Gunnison sage grouse found in parts of a 1.7 million-acre area in the two states is $290 million (see Daily GPI, Sept. 20, 2013). The Gunnison variety of sage grouse is impactful on oil/gas operations, but to a much lesser extent than the Greater sage grouse.

“There have been signals about a lot of different things [coming out of the FWS decision],” John Swartout, a senior policy adviser to Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper told NGI, adding that the state was working up to the eleventh hour trying to get the federal agency to back off the need for a listing. “You never know until you see it what the decision might be.”

Swartout said Colorado has spent more than $50 million on land conservancy and on the science surrounding the gunnison sage grouse. “The experts on the Gunnison sage grouse are all state of Colorado biologists who have been studying it for well over 20 years,” he said. “We have the best available science on the subject.”

Given the science and the fact that Colorado has gotten private landowners to implement voluntary safeguards for the sage grouse, the state is arguing vociferously with federal officials that imposing an endangered or threatened listing will hurt more than it will help.

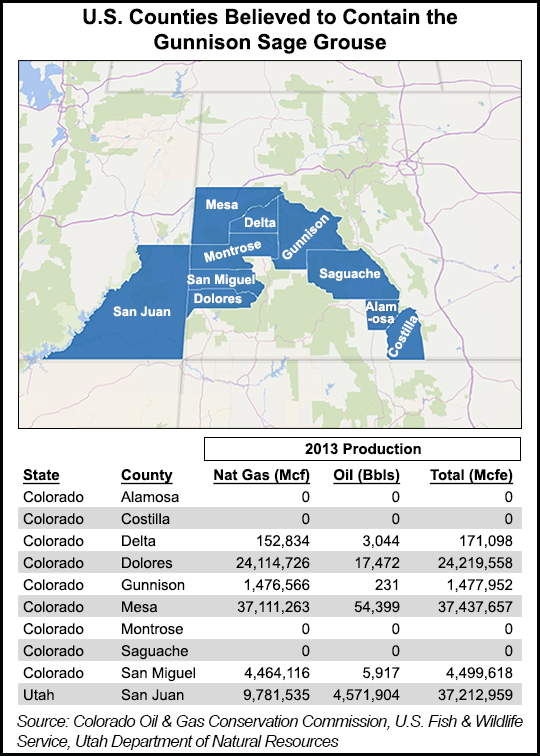

Unlike the Greater sage grouse, there is not as much exploration and production (E&P) activity in Colorado or Utah in the Gunnison sage grouse range, Swartout said.

“There are some coal mines and limited oil and gas activity within its range, but it is not the same level of conflict that exists with the Greater sage grouse in [south-central] Colorado, and there is only one county involved in [southeast] Utah,” he said. More than 80% of the Gunnison bird population does not has as much E&P conflict as the greater sage grouse, which is in the northwest portion of Colorado.

“In the Gunnison range, 97% of the private land [more than half of the Gunnison range area] has some form of protection — either protection agreements or regulatory measures by counties — for the bird,” said Swartout, noting that the counties enforce this by requiring mitigation measures before any development can take place on the property.

“They’ve done a lot [voluntarily], and more than a decade ago in negotiations the FWS told us what the state needed to focus on [to avoid a listing], and we have gotten it, doing what was asked of us, but in the last few years other issues keep being brought up,” Swartout said. “They [federal officials] are sort of moving the goal posts as the game goes along.”

A listing by the federal government on Wednesday will sour state-federal relationships, and the state’s relationships in turn with counties and landowners, Swartout said.

“So much of Colorado’s efforts over the past 20 years has been about partnership, collaboration and getting our private landowners to go the extra mile, and now this pending listing is a signal to Colorado landowners that have a very vibrant land protection program that it doesn’t do any good,” said Swartout, alleging that the prospective FWS listing will undo a lot of efforts from over the past decade to get more collaboration and cooperation from the states.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |