Seven Utah Counties Form Coalition to Advance Uinta Basin Railroad

A coalition of seven counties in eastern Utah has secured $55 million in state funding toward the possible construction of a 100-mile freight railroad into the Uinta Basin, a line that could also be used for oil and natural gas producers in the region.

The Seven County Infrastructure Coalition (7CIC) — which includes Carbon, Daggett, Duchesne, Emery, Grand, San Juan and Uintah counties — was formally assembled this summer, pursuant to the state’s Interlocal Cooperation Act. Althoughdocuments show the group will focus on joint project planning and improving the region’s “health, welfare and prosperity,” one project already stands out: the proposed Uinta Basin Railroad (UBRR).

According to the Utah Department of Transportation (UDOT), the state legislature allocated $3 million to initiate an environmental impact study on the UBRR in 2013. This year, the Utah Transportation Commission apportioned $5.2 million to continue the study.

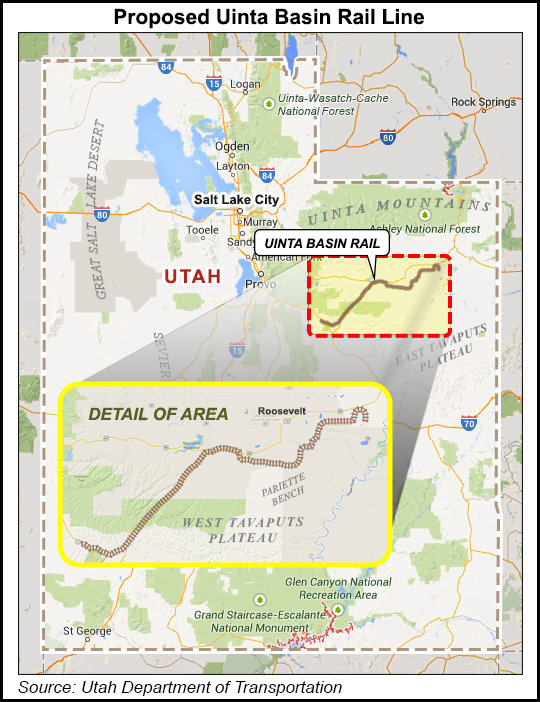

UDOT said it considered 26 possible corridors for the railroad but had to disqualify several of them because they would have had a slope greater than 2.4%, which is the operational limit for certain large trains. The corridor eventually chosen follows three existing roadways — U.S. Routes 40 and 191, and Emma Park Road — and connects with two national freight rail lines, the BNSF Railway and the Union Pacific Railroad.

Although the initial cost estimate for construction of the UBRR ranged from $2 billion to $3 billion, UDOT spokeswoman Eileen Barron told NGI’s Shale Daily that those were preliminary estimates based on national averages for rail lines and tunnels.

“There will tunneling involved in order to maintain the grade for rail,” Barron said Thursday. “There’s some really challenging terrain. We’re talking about a pretty lengthy tunnel, and we also need to consider the soil and rock type there. UDOT is actually in the process of getting a more refined cost estimate developed, and that’s expected to be shared with the public in the next six months.”

Barron added that 7CIC has submitted an application to the federal Surface Transportation Board (STB), the lead agency in evaluating the environmental impacts for the project. STB will in turn prepare an environmental impact statement for the project.

“At this point, it is too early for any decisions to be made about the financing, construction or ownership of a potential rail line,” UDOT said in a statement. “UDOT and [7CIC] are evaluating the feasibility of constructing the rail line and are exploring possible alternative routes, how the rail line would operate, and potential future funding opportunities.

“Formal decisions about the actual construction, maintenance and operation of the rail line would be made at a later date if it is determined that a feasible route can be approved through NEPA [the National Environmental Policy Act] and other permitting processes.”

A UDOT map outlining the preferred corridor shows the rail line would actually begin in Utah County, which is not a 7CIC member. It would cross briefly into Carbon County to the south before curving to the northeast and entering Duchesne County. The line would end further to the northeast, in Uintah County.

Candace Powers, fund manager with the state’s Permanent Community Impact Fund Board (CIB), confirmed to NGI’s Shale Daily on Thursday that 7CIC has applied for and received two grants totaling $55 million — a $5 million grant “for a rail study to determine rights of way, easements and feasibility of municipal rail in Eastern Utah,” and a $50 million grant “which has been placed in a trust fund for the purpose of leveraging federal municipal funding set aside for municipal rail.”

Eric Johnson — an attorney with the Salt Lake City-based firm Blaisdell, Church & Johnson LLC, and general counsel to 7CIC — said the proposal to build the UBRR was just one of several factors for the seven counties deciding to band together.

“These are rural, sparsely populated counties, and the feeling was they were getting ignored when they tried to do something as individuals,” Johnson said Friday. “Politically they will have a lot more clout when they link arms and do stuff together.

“One of the reasons that the counties are interested in this is because the benefit goes well beyond the petroleum industry. This will have a benefit to everyone in the basin. They’ve been living out there for 150-plus years, and the railroads have gone to a lot places in the world but never to them…the railroad was a convenient project that maybe helped the coalition gel right at this moment, but there’s a bigger picture of political solidarity, mutual cooperation and support. It’s a huge plus. It isn’t always easy to get disparate areas of the state to join forces.”

Johnson agreed with UDOT’s statement that it was too early to tell who would build the railroad, how it would be financed and what entity would ultimately own and operate it. But he was certain it would be a public-private partnership (P3).

“Things are still the infant stages here,” Johnson said. “Different people have different ideas about just how things are going to come together. There are a number of municipal railroads around the nation. This will certainly be a P3 project, where the public bodies own it, but I’m sure that they will look to partner with a private entity to help operate it and to run it when it’s under way. Everyone envisions it that way.

“The majority of rail lines are not owned by municipalities, but I think there are some things that the public bodies can bring to the table that help make this happen that a private rail could not, or it would be more difficult for a private rail company to do it.”

Grand County was the last to join 7CIC, it’s county council voting 6-1 to do so last Tuesday.

“Grand County tends to want to stand on its own,” Council Member Patricia Holyoak told NGI’s Shale Daily. “It’s not that we would have a big influence [in 7CIC], but at least we would know what is happening. Having a seat at the table is better than having none whatsoever — that they tell us what they’re doing rather than we know what they’re doing.”

According to 7CIC documents, the coalition is set to expire at the end of 50 years, or five years after it has either paid off all of its debts; abandoned, decommissioned, conveyed or transferred all of its interests in any projects; or after any of its projects are deemed no longer useful, whichever is later.

Under the terms of governance, a seven-member board will lead the coalition — one member for each county. The terms also stipulate that for projects that either cross county boundaries, are in more than one county or are outside the member counties, the board will “have the authority to approve the acquisition, development, construction, ownership of control of such projects by a majority vote of a simple majority of board members.”

For projects that lie entirely within a member county, the coalition’s rules also require “a majority vote of a simple majority of board members,” but the coalition must also “obtain approval from a majority of the legislative body of the subject member county” in order to proceed.

“We assume that if it’s just a single county, that the county can take care of it itself,” Johnson said. “But if a single county were to ask the coalition for help on a project, then the coalition would consider that.”

Holyoak denied that the decision to join 7CIC was divisive. “We have a really diverse community,” she said. “We have people that are far to the left, environmental, and we have those that are far to the right who are conservative. Representation from all of the community is something that we have to evaluate and try to make it work. I feel like Grand County has listened and done the best they could.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |