NGI Archives | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Rocks Are Only Part of What Sets Monterey Shale Apart, Operators Say

Today’s fast-advancing technology for well design, drilling and completion on other shale plays, are not applicable to California’s Monterey Shale, a panel of local operators last week told the Oil and Gas Awards’ West Coast Energy Summit in Bakersfield, CA.

While speakers agreed there is “huge dormant” potential in the Monterey, particularly in existing fields, they said transferring drilling and completion technologies that are pushing record production in places like the Bakken/Three Forks in North Dakota is not necessarily possible in California.

In part, that’s due to the severely different geology in California (see Shale Daily, Aug. 14), and in part it is because of the different rules applied to oil/natural gas activity in the state and a different approach historically that has resulted in extremely dense drilling areas.

Ramon Elias, a co-founder of Santa Maria Energy and now its vice president for reservoir engineering, said operators in California are becoming more aware of the need to reduce the industry’s footprint. “So we’re looking at ways to modularize our rigs and make them more compact so we don’t disturb as much surface area while we are working, and that brings up the strong tendency for more multi-well pads,” said Elias, who described himself as both an oilman and environmentalist.

Steve Johnson, senior drilling engineer for E&B Natural Resources, and Jeff Prude, a representative from the federal Bureau of Land Management’s (BLM) Bakersfield office, noted that technology and endangered species issues can also play a part of the increased emphasis on smaller drilling footprints.

“California has the highest number of endangered species anywhere in the country,” Prude said. “And we also have the highest density oilfields anywhere, too.” As a result, multi-well pads are the norm everywhere in California, according to the panelists.

With California implementing its new well stimulation (hydraulic fracturing) law (SB 4), acid use in fracking is being cut and a drive to develop “clean acid” is underway, according to Son Tran, technical advisor at MTS Solutions. And Johnson said there is no use of maximum rate drilling, noting his company wants to drill at the “optimal rate.”

“We have found, particularly in Kern County, if you drill too fast you can reduce fracking and drive up costs, so we purposely slow down the run-rate, so we don’t cause [down-hole] problems,” said Johnson. “We want to do it properly and optimally — not the fastest way.”

Elias said when he started in the oil/gas exploration and production business 43 years ago, everything was vertical; now two-thirds of the jobs are directionally drilled.

Many of the drilling techniques that are used successfully in the Bakken and Eagle Ford are not applicable in California because the formations are much different and the rocks in the West are much younger.

“Another difference is the massiveness of the California formations as opposed to the thin intervals in other parts of the country,” Santa Maria Energy’s Elias said. “And we have many more options available to use that are less demanding than other parts of the country.

“Of the parts of the Monterey that have been drilled the recovery rates have been less than 10%, so there is a tremendous potential remaining even if we only drilled on the existing fields that we are going after right now. In addition to that there is all the potential that exists in the more traditional shale-like Monterey accumulations, and I don’t think we have put together the right combination of things to tap those resources.”

While the financial community is often asking about what techniques are transferable from other successful shale plays to California, Elias reiterated that there aren’t any, necessarily. But he thinks that should not take away from a “huge dormant potential in California” found in deposits like the shallow opal-A dolomite, that are several times larger in potential than Prudhoe Bay in Alaska.

Prude said the reason that the potential for the Monterey Shale was slashed earlier (see Shale Daily, May 21) was that only a small part of the acreage has been tested by the industry and most of its has shown poor economic potential without cutting the cost of production in half or doubling production.

Undaunted, Elias talked about California having multiple alternatives, including offshore resources, shale and the opal-A dolomite. He said California could be the top reserve state in the nation if state officials permit it to happen.

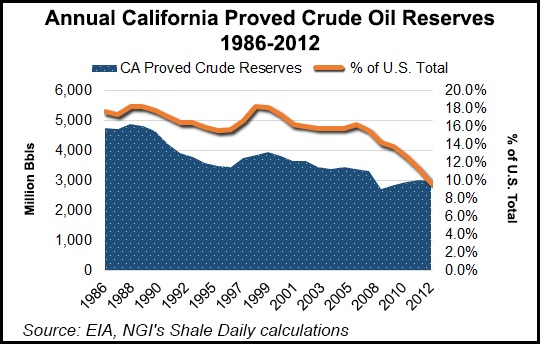

California represented as much as 18.3% of total U.S. proved crude oil reserves in 1998, but a combination of the emergence of unconventional production areas such as the Bakken and Eagle Ford shales, along with tougher environmental standards in California that have likely limited the amount of exploration and production capital spent in the state, have combined to push that figure below 10%.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |