Infrastructure | LNG | Markets | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

‘Armada’ of U.S. LNG Export Projects Readied as Global Markets Evolve

The natural gas export market is on the cusp of transforming in size and scope, with the United States in ascendency as it climbs from pauper to king in a race to carry its supple supplies overseas.

A panel of gas experts last Monday rhapsodized about the stunning makeover for liquefied natural gas (LNG) markets at the Weather & Price Tealeaves IV conference in Houston. Capra Energy Group Managing Director Tamir Druz discussed the outlook for LNG with EBW Analytics CEO Andy Weissman and IntercontinentalExchange Inc.’s JC Kneale, vice president of North American power and natural gas liquids sales.

“What’s happening now is truly transformational, both in size and scope,” Druz said of global LNG expansion. This is the second year in a row for the “biggest ever growth spurt,” both percentage-wise and in absolute terms.

At least 140 million metric tons/year (mmty) of LNG capacity is forecast to come onstream worldwide over a five-year period from 2016 through 2020, versus a base of 250 mmty at the end of 2015, Druz said.

Adding more than 50% of LNG capacity over a relatively short period of time is the “likes of which we have never seen before,” he said. “To my knowledge, there’s only one year prior to this period where more than 20 mmty was added in a single year.”

About half of the new LNG capacity, nearly 70 mmty, is slated to be cargoes from U.S. shores. At that level, the United States would be propelled “from a position of really producing trivial amount of LNG” via the ConocoPhillips Kenai project in Alaska, “to a situation where it will become the No. 2 or No. 3 producer,” Druz said.

Kenai LNG, which is set to be mothballed this fall, was the first and for a long time the only export plant in the United States.

U.S. ascendency, joining in step Australia’s surging export capacity, will become “real rivals” to long-time world global leader Qatar.

The question is, will worldwide LNG demand keep pace?

“Yes, it can, a resounding yes, it can,” Druz told the audience. There are about 40 import markets, with the top five — Japan, South Korea, China, India and Taiwan — collectively consuming about 70% of LNG worldwide today.

“South Korea may pose a much larger bullish risk than almost anyone expects,” Druz said. South Korean President Moon Jae-in “hates nuclear and coal, and he’s done more than anyone expected to reduce reliance on both. Natural gas is the only place to go, and if his plans materialize, we could see a major spurt in South Korean demand growth…We see that as a real upside risk for demand and pricing.”

The demand worldwide also is broader, and “very deep with the involvement of big players,” Druz said. Pricing is better, too with the fundamentals “perhaps rosier than people expected coming into the LNG supply wave.”

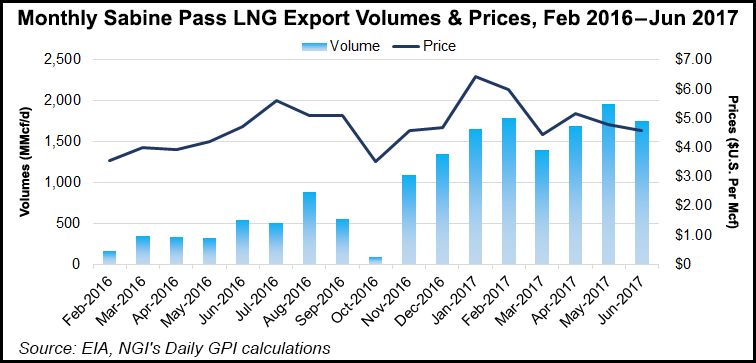

LNG prices appeared unable to find a floor following the sharp price declines in 2014 and 2015, but a $5.00/MMBtu level has served as a soft floor since 2016, Druz said.

“Seasonality has intensified, with winter premiums exceeding the levels seen in recent years,” and longer term structural contango has continued to strengthen.

LNG may be a global commodity, but customers increasingly are sourcing cargoes closer to home, according to Capra research. For example, Australia is building substantial market share in northeastern Asia from Qatar and other Persian Gulf suppliers. The United States quickly is becoming a supplier of choice to Latin America.

“This dynamic should intensify as existing long-term contracts expire, and as destination clauses begin to disappear,” Druz said. “No one disputed that LNG cargoes could be sent from one end of the world to another. Now the question is, should LNG cargoes be sent from one end of the world to another?”

Domestic gas exports likely will have a “transformational impact on global gas and electricity markets,” according to Weissman. “Over the next three to four years, more often than not, the impact will be to drive natural gas and electricity prices lower, but volatility could be extreme, starting almost immediately.”

Weissman “profoundly” believes the global markets are on the “cusp of one of the most significant impacts on gas and electricity markets.” U.S. gas prices today are driven by weather and “more important, pipeline infrastructure, which is critically important. It affects decisions made by U.S. producers as to how rapidly to grow production…”

However, what’s apparent to Weissman is that over the next few years demand for U.S. LNG exports “will rival and surpass weather as the core driver of electricity and U.S. gas prices.”

Export capacity “is about to explode.”

No LNG was traded in the United States during 2016, he noted. “We now trade for 2.8 Bcf/d currently. That’s now, that wasn’t true three weeks ago. If you go back four months ago or so, it was more like 1.4 Bcf/d. We’re in the very early stages of a very steep ramp-up to 12 Bcf/d by the beginning of 2020…

“This isn’t theoretical, like ”maybe’ it could happen. These are projects being built now, fully subscribed, fully funded and money is sitting in the bank. All the projects will be finished…We’ve never added that kind of capability.”

Domestic exports face competition, but U.S. gas can be delivered at a lower cost than about anywhere in the world. And appetites are huge.

“U.S. developers are chomping at the bit to build another 24-plus trains,” Weissman said. “We will be the future supplier of natural gas to the world. The bottom line is, the United States is one of the potentially lowest sources of incremental gas supply.”

Domestic projects are structured with tolling agreements, making it a more attractive place to build. U.S. LNG developers have less risk, as they build the liquefaction plans and the docks, then secure LNG buyers.

To illustrate how much more viable domestic projects are, Weissman noted that outside the United States, no final investment decisions for LNG export terminals have been issued since 2015. In the United States, however, “there’s been an armada of additional export projects looking to go forward.”

On the contracting side, ICE has seen a “pretty incredible growth curve this year, which frankly has been a long time coming,” said Kneale. “The first contract was in 2010 and it then spent six years languishing…

“It was not a successful contract to our mind. It was proving pricing, but as an exchange, we make money when it trades rather than being a free pricing service.” Last year, however, ICE “saw something was up.”

New participants not considered traditional LNG players “began taking positions, buying cargoes without production, selling without production,” Kneale said. “It’s a healthy feature of this new market.”

This year the market has embraced LNG futures trading, with growth in overall LNG trade, particularly spot and short-term transactions, and heightened interest in protecting margins and managing price risks. The competition is growing and the spreads are narrowing.

The Gulf Coast still has an element of a “lot of hurry up and wait,” Kneale said. “We can get accurate prices responsibly, but we just need more activity in the Gulf Coast to mirror what’s happening globally.”

Kneale is working on expanding the global outlook as gas increasingly leaves U.S. shores.

“What we do see happening more and more is customers thinking about the front end of the curve. There are big reactions to price moves…because certain folks are putting bets in the options market…”

Longer term decisions about LNG cargoes are being made, and new infrastructure is changing the way hedges historically have been built. “But anecdotally speaking, production zones are shifting.”

Dominion has become “the largest location for regional gas now in the United States, even challenging AECO in North America,” Kneale said. The Houston Ship Channel also “has seen massive growth this year, and that wasn’t immediately obvious.”

The Mexico gas export market also is evolving, and “over time, that will grow out with pricing points.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |