NGI Archives | LNG Insight | NGI All News Access

Argentina’s Vaca Muerta, LNG Ambitions Face Uncertainty as New Government Settles In

Argentina’s prolific Vaca Muerta shale play is going through a period of uncertainty as the new leftwing government in Buenos Aires devises plans for its energy sector, according to analysts.

“There is uncertainty in the short term,” the vice president of the Argentine Energy Institute, Gerardo Rabinovich, told NGI. “Right now, the focus of the government is on the renegotiation of its foreign debt, and they are throwing everything into that. And that means that in other activities, there isn’t as much certainty.”

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) recently called Argentina’s foreign debt obligations “unsustainable” given the depreciation of the local peso against the dollar, high inflation, and plummeting reserves of foreign currency. The government is currently engaged in talks with the IMF to revamp around $100 billion in debt, but so far nothing has come of it.

As a result of the uncertainty, production of natural gas and oil from Vaca Muerta could take a hit, according to Wood Mackenzie’s Ignacio Rooney.

“If you look at the numbers, there is nothing surprising, production has not gone down in oil or gas, and if it has it’s because of seasonality, and not something to worry about,” Rooney told NGI. “But if you look at levels of activity, you will see a drop since August of last year. After the primary elections, investors and operators were reluctant to make long term commitments knowing that the administration was about to change.”

Business friendly Mauricio Macri lost primary elections in August, signaling an end to an administration that did much to turn around the energy sector. After these elections, which occurred two months before the general elections won by left-wing Peronist rival Alberto Fernandez, the Argentine government froze energy prices, leading to less attractive market conditions.

Activity in Vaca Muerta declined from 43 rigs in August to 29 rigs in December. The number of monthly hydraulic fracturing stages in Vaca Muerta fell from 676 in August to 346 in January, according to official data. Still, overall gas production rose 5% in 2019 to 135.2 million cubic meters per day (MMm3/d), or 4.7 Bcf/d, from 128.8 MMm3/d in 2018.

“The hypothesis is that production won’t be impacted this year, but then at the end of this year or 2021 decline from production in Vaca Muerta might be felt,” Rooney said.

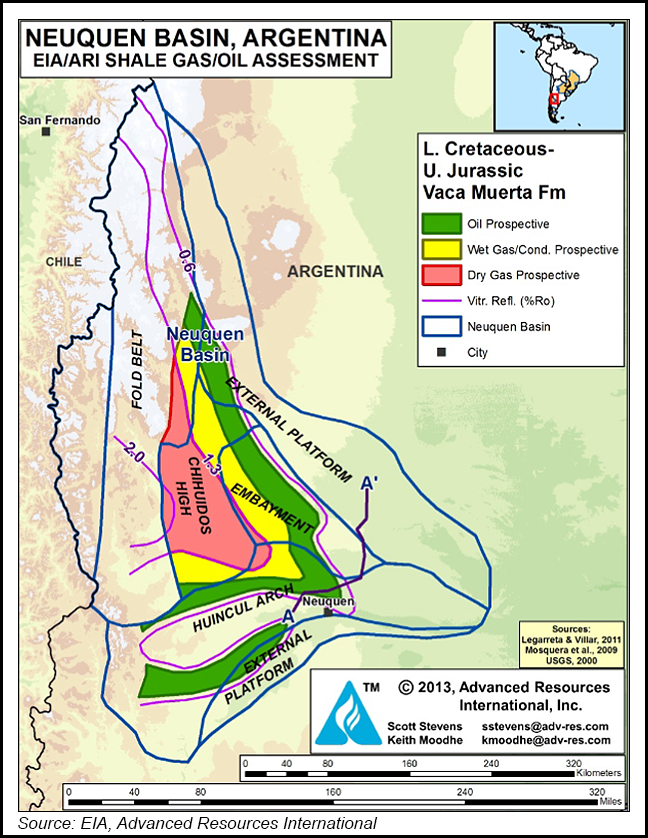

Vaca Muerta, one of the largest resources of unconventional natural gas in the world, has been seen as a cure to Argentina’s economic ills, which makes the slowness to action frustrating, according to Rooney.

“During campaigning the new government said energy would be a star, a real foreign direct investment opportunity, so there is criticism that there has not been a clear north for the energy area, that energy regulation has taken some time to be disclosed or discussed.”

Crucial projects for the natural gas sector, such as a billion-dollar natural gas pipeline from Vaca Muerta to Buenos Aires have also been put on hold. Originally, a tender was set for the pipeline on Oct. 31, but the new government scrapped it and has not made mention of it since.

The lack of the pipeline would seriously dent Argentina’s liquefied natural gas (LNG) export plans. The country started shipping out small scale LNG exports last June, the first of its kind. The LNG was produced on Exmar NV’s Tango floating LNG production barge, at the Bahía Blanca port, and using natural gas piped in from Vaca Muerta. The vessel has production capacity of 500,000 metric tons, or about 0.07 Bcf/d, and could produce up to eight LNG export cargoes per year, according to the U.S. Energy Information Agency.

McDermott International Inc. in July was also awarded a “sizeable contract” by Argentina’s YPF SA to provide pre-Front End Engineering Design services for a 5-10 million metric ton/year (mmty) liquefaction facility to serve producers developing the Vaca Muerta.

Wood Mackenzie last year saw Argentina LNG ramping in 2024 with LNG production volumes reaching 6 mmty which could grow to 10 mmty by 2030.

“But if you want large scale LNG sendout, you need a pipeline,” Rooney said.

There is also some discussion about whether Argentina will continue to send out natural gas to its neighbors. In late 2018 and amid much fanfare the first molecule of Argentine gas for electric power generation in more than a decade was sent across the border via the GasAndes pipeline to Chilean power generator Colbún.

One month later, the Gasoducto del Pacífico SA pipeline was reopened after being shut in 2008 with gas flowing from Vaca Muerta, including from ExxonMobil Corp., to LDC Innergy in Chile’s central-southern Biobío region.

“LNG exports have been symbolic, and I didn’t take it as something important,” Rabinovich said, “but lower production could also affect exports to Chile and other places.”

Still, while Rabinovich sees activity continuing to fall over the next few months as “internal conflicts and a lack of articulation of policy” from the energy secretariat continue, there is little sign that foreign companies are going to pull out. Almost all the majors are in Vaca Muerta and have established solid positions in the formation.

In January, Norway’s Equinor SA and Royal Dutch Shell plc jointly purchased a 49% interest held by Schlumberger Ltd. in the Bandurria Sur onshore block covering around 56,000 gross acres in the central area of the prolific Vaca Muerta play.

“These companies wouldn’t increase their exposure if they were thinking of pulling out,” Rooney said. “There is uncertainty, but I don’t see an exit of the country.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |