E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Amid Turbulent Times In Mexico, Is Pemex IPO a Bridge Too Far?

As a wave of economic liberalism lapped on the shores of Latin America in the early years of the 21st century, energy reforms were enacted in Colombia and Brazil, where the state-owned oil and natural gas companies were floated on stock markets with remarkable success. In fact, the $70 billion offering Brazil’s Petroleo Brasileiro (Petrobras) in 2010 was at the time the world’s biggest ever initial public offering (IPO).

Mexican President Enrique Pena Nieto resisted the siren songs of many in the business community who had wanted him to follow suit with the 2013-14 reform of state-owned Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex), a symbol of national sovereignty for generations following the 1938 takeover of the U.S. and British oil companies.

Pena Nieto instead firmly voiced opposition to any “privatization” of Pemex, whose monopoly of oil and gas was removed under the sweeping reforms. However, after faltering in the first of the country’s two upstream auctions, the first in almost eight decades, the reform has confounded many of its critics, netting more than $200 billion of investment, according to Energy Secretary Pedro Joaquin Coldwell.

Now, with a presidential election looming on July 1 and the inauguration of a new government due in December, Jesus Reyes Heroles, one of the biggest political guns in the currently ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) has called for a Pemex IPO.

The absence of a Pemex IPO, was a “flaw” in the energy reform, he told a recent symposium in Houston at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy.

“The end of this administration, in my view, would imply the end of the commitment not to sell assets of Pemex, and that would open up the door for an IPO of Pemex,” Reyes Heroles told the symposium.

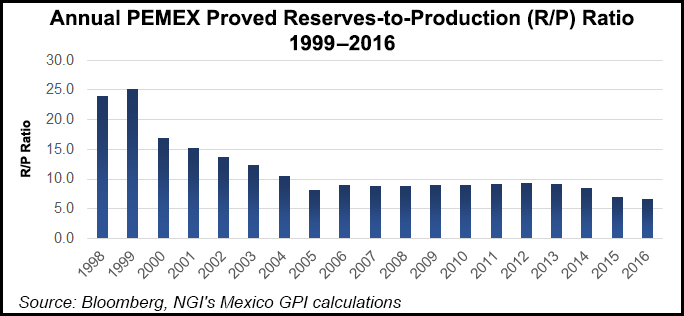

Without a Petrobras-style “Big Bang,” Pemex has been left to shoulder the burden of lower crude oil prices, sharply lower natural gas production and the near collapse of the nation’s refineries before the promised fruits of the promised investment in the reform can be harvested.

The Mexican Constitution allows a six-year term for each president and no re-election. Therefore, said Reyes Heroles, Pena Nieto’s “no privatization” commitment will have expired on Dec. 1.

Chief energy counsel Miriam Grunstein of the Mexico-based Brilliant Energy Consulting, shared the presidium with Reyes Heroles at the forum at the Baker Institute, where she is a nonresident scholar.

While agreeing with Reyes Heroles on the plight of Pemex, Grunstein believes that an IPO would be a nonstarter, she told NGI’s Mexico GPI.

“These are very sensitive political times in Mexico, and an IPO for Pemex would just be too hot to handle,” Grunstein said.

A consultant to one of the Big Oil companies actively working in Mexico agreed, though he was not willing to be identified.

“The murder rate has hit an all-time high, including some killings that have had political implications,” he said. “On top of that, there are serious corruption scandals of a type that used to be quietly hidden away in the old days. Widespread poverty continues and the economy remains near-stagnant. These are very difficult times indeed.”

The early polls of the electoral campaigns show that Jose Antonio Meade, Mexico’s former finance minister, is lagging badly in third place as candidate off the PRI, the party of Reyes Heroles and Pena Nieto. Indeed, Meade was not chosen as the PRI candidate but hand-picked by Pena Nieto.

The front-runner is Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, regarded as the most unlikely of all to favor a Pemex IPO. Some pundits think he aims to overthrow the energy reform, but most believe that if he were to win the presidency, he would be in no position to reject investment.

As a third-time candidate for the presidency, Lopez Obrador is well known to all Mexican voters and followers of the nation’s politics. Usually described as a leftist, Lopez Obrador is more than an old-style nationalist member of the PRI, to which he once belonged, rather than a European-style social democrat. His party is known as the Movement for National Regeneration (Morena).

These days, the PRI is controlled by technocrats, such as Reyes Heroles and Meade, educated in the United States and at the elite Mexican university, ITAM, i.e., the Autonomous Technological Institute of Mexico. Meade is not a member of the PRI, though he could be considered a fellow traveler.

While Meade, 48, and Lopez Obrador, 64, are predictable, the opposite is true of the third candidate, the 38-year-old Ricardo Anaya of the National Action Party, aka PAN. Followers of the PAN, routinely described as the pro-business party, are generally regarded as conservative and family-oriented.

Anaya, an eloquent public speaker became the “wonder boy” leader of the PAN two years ago and now he leads it in what many PAN members regard as an unholy electoral alliance with the moderate leftist Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD).

However, Anaya, considered slightly nerdish, has become, at least in his television commercials, a guitar-strumming friend of the nation’s young and dispossessed. His policies appear to be more radical than those of Lopez Obrador. And what about his family values? His family lives in Atlanta, GA.

Anaya supports doubling Mexico’s $5/day minimum wage, though in itself that is probably not important. The “informal” Mexico economy covers about 40% of the nation’s workforce, and most earn more than the minimum wage. People who work at the pumps in many gasoline service stations that pay no wages say that they earn about $20/day in tips, at least in the cities.

However, Anaya has another card up his sleeve, a guaranteed universal minimum income, a proposal that goes beyond the welfare systems so popular in Europe.

What is more remarkable for people not living in Mexico, rather than the metamorphosis of Anaya, is that, of the three candidates, only Lopez Obrador, has made policy statements of any substance on such a key issue as energy.

Lopez Obrador’s pledges are of investments in new refineries, which analysts have opposed as a huge expense when the crude can be processed at much lower cost in U.S. Gulf Coast facilities.

The energy reform has been described by Pena Nieto supporters as being the “jewel in the crown” of his reform program, but scarcely a word has been said on the campaign trail, much less mention of an IPO for Pemex.

That is quite normal in Mexico, where the outgoing president’s slate is traditionally wiped clean by would-be successors.

Reyes Heroles is well aware of that, steeped in the political traditions of Mexico. His late father, of the same name, was the ideologue of the modern PRI, unable to bid for the presidency only because of his Spanish parentage. At the time, the law stipulated that a president and parents had to be Mexican-born.

Reyes Heroles junior has been director-general of Pemex, energy secretary and ambassador to the United States. As Pemex chief, at the beginning of the 2006-2012 administration of Felipe Calderon, he was asked at his first press conference about the future of the pet project of Calderon’s predecessor, Vicente Fox, regarding a $10 billion refinery to process Mexican crude in Central America, which had already been invited for tender.

Reyes Heroles said then that the refinery project was not a priority for Pemex. No announcement was made, but the tender was cancelled. The slate was wiped clean.

Of course, the energy reform, unlike the Fox refinery, is enshrined in the Constitution. Beyond that, however, an IPO for Pemex appears to be a bridge too far for even one of the staunchest supporters of Pena Nieto.

Peña Nieto is rated in opinion polls — including one promoted by the prestigious Grupo de Economistas (GEA) consultancy — as the most unpopular Mexican president since polls were first published in Mexico at the end of last century.

For those keeping track, Reyes Heroles was a co-founder and is executive president of GEA.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |