Regulatory | Infrastructure | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

NY Part 1: NatGas Hits Political Wall in New York, As Industry Fights Losing Battle

*Part one of four. This series examines the effects New York state’s energy policies are having on Appalachian natural gas producers, consumers and the Northeast. It explores the political, operational and economic issues related to the state government’s position on natural gas. Part one explores Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s role in fermenting that position and what it’s meant for infrastructure projects trying to pass through the state.

The natural gas industry is losing in New York state, where a political wall has been erected to stop fossil fuel, which is not only costing producers opportunities to grow, but blocking nearby states from receiving vital supplies. The situation appears unlikely to change anytime soon.

Nevertheless, the industry has a renewed hope in President Trump’s pro-energy agenda, believing his administration will intervene in some way to jump-start stalled pipeline projects or open tribal lands in the state to unconventional natural gas development.

Like it or not, it’s become increasingly clear that more shale gas is not welcome in New York. Ask most in the industry and they’ll tell you why: “It’s a Cuomo thing. It’s political.” Many would rather not be quoted when discussing Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who has doggedly pursued a vision for the state’s energy future and inserted himself squarely into the party’s efforts to combat climate change and promote renewable energy.

“Everybody is hurting nationwide because of commodity prices,” said Brad Gill, executive director of the Independent Oil and Gas Association of New York (IOGANY). “Every state has the price battering; every state has the public opposition to fossil fuels — even though New York is Ground Zero, but all the other states can hydraulically fracture (frack) gas if they want to. So we have the third leg of the triple whammy here, and that is this governor. All the other states are battling the same things, but in New York, we’ve had the door slammed shut.”

That closed door has had an impact on neighboring states.

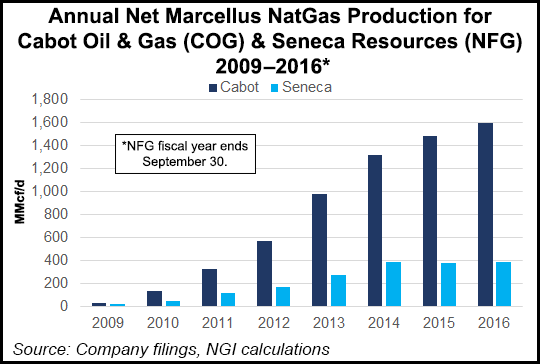

Pennsylvania shale drillers produced 5.1 Tcf across the border in New York’s backyard last year. Producers in northern Pennsylvania, however, have hit a wall when it comes to reaching lucrative markets in New England.

Subjected to a robust regulatory review process, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) denied both National Fuel Gas Co.’s (NFG) Northern Access expansion project and the Constitution Pipeline key water quality certifications (WQC) for stream or wetlands crossings under Section 401 of the federal Clean Water Act (CWA). More than 1 Bcf/d of takeaway capacity is stuck in regulatory limbo and mired in litigation.

”Lousy Regulatory Treatment’

NFG CEO Ronald Tanski curtly told financial analysts in May that the Buffalo-based company is receiving “lousy regulatory treatment in New York state,” suggesting at one point that a move out of state was not out of the question and saying the company would increasingly invest elsewhere.

“Let’s be clear, we’d still love to achieve some sort of negotiated solution for that project,” Tanski said the same day when asked about Northern Access. “But when the governor won’t take 10 minutes to respond to repeated requests of the CEO of a New York headquartered company with 1,200 employees in the state and the commissioner of the DEC won’t return my calls, I mean who are we going to negotiate with?”

Each project has challenged the DEC’s decisions in federal court. The pipelines are now threatened altogether.

“These projects were really developed to help New England serve their demand,” said BTU Analytics LLC analyst Matt Hoza. “And now that’s not going to happen. Atlantic Bridge, is due on at the end of this year, after that project we don’t foresee any other projects really connecting that supply in Northeast Pennsylvania to that demand market in New England.”

What’s more, after nearly seven years of regulatory review that began with an executive directive before Cuomo took office, the state officially banned high-volume hydraulic fracking in 2015, denying opportunities for the state’s smaller producers, which long ago saw demand outpace the supplies pulled from conventional reservoirs. Additional resources were swept off the table for larger independents, too.

Yet Cuomo is popular across much of the state.He garnered more than 50% of the statewide vote in 2010 and 2014. Wide swaths of New York, both Upstate and Downstate, are pockmarked with local fracking bans, as well.

The governor has acknowledged that gas is a necessary bridge fuel, but nothing more. New York obtained 24% of its electricity from renewable sources in 2016, according to the Energy Information Administration. Under Cuomo’s Reforming the Energy Vision (REV), renewable contributions would increase to 50% by 2030. The program is underpinned by significant state investments and plans for “green” job creation.

“Now that New York has built a foundation for the renewable energy system of the future, the state must double down by investing in the fight against dirty fossil fuels and fracked gas from neighboring states,” Cuomo said in his 2017 state-of-the-state address. The Cuomo administration did not respond to questions from NGI’s Shale Daily regarding the state’s energy policies.

The Marcellus Shale Coalition and the American Exploration & Production Council labeled New York as “rogue” in a court brief supporting NFG. The Constitution and Northern Access pipelines, along with the state’s fracking ban, have become powerful symbols of anti-fossil fuel sentiment.

“The state level is where the environmentalists should be waging their war,” said attorney Richard Drom, who practices before FERC at Washington, DC-based Eckert Seamans Cherin & Mellott. “I don’t think they’re going to be successful at all at the federal level.”

Constitution and Northern Access long ago were approved by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. The natural gas industry argues that New York’s denial of the pipelines, and its fight with others, threatens interstate commerce and emboldens an environmental agenda that could find more activists targeting state-issued WQCs to upend pipeline construction.

Unusually Long Pipeline Reviews

Just before midnight on Friday, April 7, the DEC emailed NFG a 13-page letter denying Northern Access a WQC, noting the project’s plan to construct 71 miles of pipeline in the state failed to meet its water quality standards and would negatively impact the environment. The letter, NFG has argued in the the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, was “superficial, conclusory and repeatedly contradicted by record evidence.”

About a year before that, on Earth Day 2016, the DEC denied Constitution Pipeline Co. LLC a WQC, claiming the permit application was incomplete. Both denials came after unusually long reviews, roughly three years each.

The companies have argued in court and before FERC that the DEC’s denials were “arbitrary and capricious,” far exceeded the scope of the state’s authority under the CWA, were politically motivated and eclipsed the statutory timeframe in which a decision should have been made. The Second Circuit has been asked to review and vacate the DEC’s decisions. NFG also has asked FERC to allow it to proceed without state permits, arguing the Natural Gas Act (NGA) preempts the state’s authority.

The Circuit Court recently denied Constitution’s challenge, ruling DEC is entitled to its review under relevant federal laws.The court, however, said it lacked jurisdiction over how long it took DEC to issue a denial letter, and said it was a matter for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.

Both sides welcomed the court’s opinion as a victory, and Constitution’s backers still see a “path to final approval,” according to spokesman Keith Isbell. It’s unclear what’s next for Constitution. Isbell said after the ruling that “we are weighing all options.”

DEC has pushed back in court, insisting it has broad authority under the CWA for review. FERC’s certificates are predicated on the companies obtaining state approval, and DEC argues that its “thorough and transparent” reviews gave the companies ample opportunity to comply with state standards or submit additional material.

“Under Gov. Cuomo, New York has nation-leading climate change policies from ramping-up renewable energy production through strategic investments and setting stringent safeguards to ensure public health and the environment are protected from the potential impacts of proposed pipelines and fossil fuel infrastructure,” said DEC spokeswoman Erica Ringewald, when asked about the state’s energy policies and the agency’s regulatory processes.

“DEC subjects all applications for environmental permits to a transparent and exhaustive review process that encourages public input at every step of the process.”

DEC, Constitution and NFG representatives declined to comment specifically about the ongoing litigation. NFG spokeswoman Karen Merkel said the company is unfazed by the outcome for Constitution in the Second Circuit.

“We continue to review the decision,” she said. “But our circumstances are different than the DEC’s decision in Constitution, which was based on an alleged failure to provide sufficient information. We remain confident in our appeal.”

Constitution initially submitted its WQC application in August 2013. The company subsequently withdrew and re-submitted it in 2014 and in 2015, a move DEC argued extended the review period each time by up to a year.

NFG and Constitution submitted thousands of documents, conducted weekly conference calls, had regular meetings and sent countless emails to the agency, they said. Both also claim DEC repeatedly indicated its satisfaction with the applications long before they were denied.

In a sworn declaration in 2015, submitted by Constitution’s Environmental Project Manager Lynda Schubring, which was later struck from the Second Circuit case record over DEC’s objections, DEC permitting chief Christopher Hogan said the agency “was ready to issue the permits, but the governor’s office was not.”

Schubring said she continued to contact Hogan until Constitution received its denial letter, saying that “at no time did he inform me that DEC was waiting for additional information from Constitution.” DEC claimed in subsequent court documents that the declaration and others submitted misrepresented conversations between the agency and company officials, adding that it couldn’t adequately respond without creating a “trial by affidavit.”

For its part, NFG has asked the Second Circuit to order discovery into New York’s decision-making process to determine “whether the governor or any political appointees exerted or may continue to exert improper influence” on its regulatory approvals. The company has charged that DEC’s denial was “pretextual,” pointing to comments Cuomo made in an editorial board meeting with The Buffalo News days after the denial was issued. He suggested that the economic impacts of the project were outweighed by the environmental impacts.

DEC has dismissed that as conjecture, saying in court that the agency’s “determination, on its face, is based solely on water quality considerations. It contains no mention of economic issues.” The agency added that pointing to a newspaper article fails to meet the exacting standard for vacating its decision and argued that NFG put words in the governor’s mouth by selectively plucking from his statements.

Struggling With DEC

NFG also argued in court that the DEC has approved similar natural gas projects in recent years, such as Algonquin Gas Transmission LLC’s 132,700 Dth/d Atlantic Bridge expansion, which received water quality permits from New York in May 2017. But DEC indicated in court documents that those projects are not at all similar, saying in most cases that they were smaller, in already disturbed rights-of-way and involved replacing or installing less than 20 miles of pipeline.

DEC officials told NGI’s Shale Daily that the agency has approved at least seven WQC under the CWA for interstate natural gas pipeline projects since 2012. When asked if those projects were related to shale gas development, officials said the agency does not “categorize pipeline projects under review by extraction method or the type of gas that may be transported through them.”

The time it takes DEC to review and make a decision for such permits, according to the officials, is dependent on the specific circumstances of the proposed project, including its scope, potential environmental impacts and the cooperation of sponsors in providing necessary information.

The bulk of both pipelines would be built in New York. Those operations would not be without environmental risks. Combined, the projects would cross more than 442 waterbodies and 153-plus acres of wetlands. Several environmental groups have intervened in court on behalf of the DEC, arguing that construction would have consequences for critical habitats and impact water quality in a way that FERC failed to acknowledge when it approved the pipelines.

Problems of this kind are not unusual for long-haul pipelines. FERC’s pipeline reviews are voluminous and include specific mitigation conditions in detail.

The steps NFG and Constitution have taken to detail their struggles with the DEC and any extraordinary executive involvement, which included a separate lawsuit by NFG to obtain related documents under the state’s Freedom of Information Law, could be fruitless.

Generally, a court reviewing an agency decision is restricted to the administrative record compiled by that agency when it made the decision. The Second Circuit found that there was ample administrative evidence to support DEC’s decision to reject Constitution’s WQC application. NFG has suggested, depending on different scenarios, that its case could drag on until 2020. Even if the court were to rule in its’ favor, the applications would likely be remanded back to DEC for resolution.

Consider the ill-fated Islander East pipeline. In 2006, Connecticut’s environmental regulatory agency, at the time headed by former U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Gina McCarthy, denied the project’s WQC. The denial was remanded to the agency, which again denied the application.

Turning to White House For Support

Williams, which would construct and operate Constitution, doesn’t want an Islander East repeat. CEO Alan Armstrong anticipated the second circuit outcome on the company’s 2Q2017 earnings call when he said, “it’s a little bit unusual for a court to overrule an agency like that.”

Millennium Pipeline Co. LLC has also been battling New York since 2015 over what it claims are unnecessary permitting delays for an eight-mile lateral to feed a gas-fired power plant in the state. The DC Circuit Court in June declined Millennium’s request to force state regulators to expedite its WQC review, suggesting the pipeline could bypass the agency and go directly to FERC, which already approved the project.

Armstrong said that ruling was encouraging, but the company has turned to the White House “to move things along,” as others have.

IOGANY’S Gill views President Trump’s policies as one of the last glimmers of light for the state’s beleaguered natural gas industry. “Absolutely, there’s beginning to be some loosening of the reins,” he said, when asked if he thinks Trump might intervene. “We’ve seen it with Dakota Access, we’ve seen it with Keystone,” he added of those previously stalled projects.

The Trump administration did not respond to requests for comments about the situation in New York or whether the president has considered his options to help the industry there.

“We’re seeing early indications of a muscular energy policy under Donald Trump,” said Mike Caputo, a political operative who worked as Trump’s campaign communications adviser. “President Trump — I can tell you with great confidence — he’s told me more than once that he’s really bothered by Cuomo’s hydraulic fracturing ban, very bothered by it.”

Caputo recently delivered his remarks before the IOGANY’s summer meeting in Clymer, NY. Caputo managed Republican gubernatorial candidate Carl Paladino’s unsuccessful campaign against Cuomo in 2010 and was later part of efforts to recruit Trump to run against the governor in 2014.

“He’s going to take an early look at the interests of the Seneca’s and other tribes here in New York and maybe help with Cuomo’s energy policy on Indian lands,” Caputo told the crowd. “Not sure it’s going to happen, but I know they’re talking about it right now and they think that New York is the first place they go.”

Caputo’s claim could not be independently verified. Many of the state’s Native American tribes have opposed fracking. Caputo said that if the administration can put political controversies behind it, however, the energy sector could be among some of the first to see significant changes.

Trump has already signed an executive order hailed by industry trade groups that calls for the federal government to expedite its review and permitting of major infrastructure projects, such as oil and gas pipelines.

Sources said they hope the Trump administration can influence FERC to intervene in New York and get Constitution and Northern Access going again. It’s a wait and see situation. Two of Trump’s nominees have been confirmed and two more are expected to be confirmed and join the Commission in September, giving the agency a Republican chairman and a majority of three Republicans.

The various interest groups are attempting to gage the firepower in the new Commission. Laws and rules have been re-interpreted, bent and stretched before by aggressive Commissions, most notably the one in the early days of deregulation that turned interstate natural gas pipelines into common carriers.

No ”Rubber Stamp Factory’

Drom, of Eckert Seamans Cherin & Mellott, said the Commission is hamstrung in a way by the NGA, which he said clearly stipulates that FERC must almost always approve a certificate as long as a company has customers and it meets the law’s criteria.

It’s not a “rubber stamp factory, there’s a definite process to go through,” Drom said, reacting to environmentalists’ claims. “I think FERC is entirely correct in staying out of these battles. Congress gave them limited authority. If the pipeline is not following state laws, then the certificate is invalid. It’s up to the state to go to FERC and demonstrate that the state laws aren’t being followed.” Conversely, Drom said FERC only approves projects if they meet state standards.

That juxtaposition is one reason why the Delaware Riverkeeper Network (DRN) and other environmental groups are pushing to reform the NGA. DRN’s leader, Maya van Rossum, said FERC “misinterprets” its mission and always applies the NGA in a way that is “supportive of a pipeline project and against the people.” She said her organization is pushing for Congressional hearings into the Commission’s “abuse of power” to identify the reforms that need to be introduced and implemented.

Given the political landscape, she acknowledged what an uphill battle that is. She said Cuomo has not catered to a certain voting base in New York, adding that DRN and its allies opposed to fossil fuel development have had to push harder than they wanted to for victories there.

Even still, she said New York’s stance is encouraging and could help other states take bolder positions against the industry. “We’re looking for a champion. Someone who will call for the right kinds of actions.”

Cuomo The Pragmatist

Could Cuomo be that champion? He entered office in 2011 in the middle, aligning with the liberal voting base on social issues and governing as a moderate centrist on economic issues. Since his first term, Cuomo has successfully tackled gun control, marriage equality, a $15 minimum wage, paid family leave and free tuition at state colleges and universities — all important national policy priorities for the Democratic party — leading the news media and many interviewed for this series to wonder if he’s considering a run for president.

“He came into office wanting to take a more centrist position, wanting to be more open-minded, open for business, including wanting to open things up for natural gas development,” said Robert Shum, a political science professor at the College at Brockport in Upstate New York. Shum said Cuomo is a pragmatist, like most politicians.

“People talk about Cuomo changing and it’s like, ”well yes,’ he saw where the votes are. He saw that the environmentalists could deliver votes,” Shum said. “It’s probably not unfair to say he’s moved in that direction. Look elsewhere in energy. He’s always balancing, always hedging.

“In nuclear, he’s announced that he’s decided to shut down the Indian Point plant on Long Island because that’s a way to appeal to environmentalists,” he said. “But he’s also hedging and allowing for subsidies to be put in place for two other plants. That’s his modus operandi; to be pragmatic and to do whatever is necessary.”

The same day Trump announced his intent to withdraw the United States from the Paris Agreement, Cuomo, California Gov. Jerry Brown and Washington Gov. Jay Inslee announced the creation of a climate alliance so that states may advance the global agreement’s goals to reduce climate change impacts.

“As the federal government abdicates its responsibility on climate change, New York is a driving force for protecting our natural resources for future generations and ensuring New York’s environmental review process is the strongest in the nation,” DEC’s Ringewald said in response to a question about how environmentalists view the agency’s efforts to regulate the oil and gas industry.

Regardless of a presidential run, Cuomo is viewed by many as a shoo-in for a third term as governor. Sources said that while there’s frustration among some in the legislature about state energy policy, the focus has waned since New York banned fracking, which one executive called a “defining moment.”

“With the pipeline issues, I think it’s sort of a hangover from the fracking ban,” Shum said. “It sort of generates a momentum of its own, where Cuomo now has this brand where he sees that he can get votes from the cities and the environmental groups.He can brand himself as a progressive and that gives him an advantage over other candidates.

“I don’t know now whether the industry could do something else in terms of rallying support. It’s harder with pipelines.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |