E&P | NGI All News Access | Permian Basin

Apache Partners to Monitor Water Quality in Permian’s Alpine High

Apache Corp. is partnering with chemists at the University of Texas at Arlington (UTA) to track groundwater and surface water quality as it begins to bear down on development within its ballyhooed Alpine High discovery in the Permian Basin of West Texas.

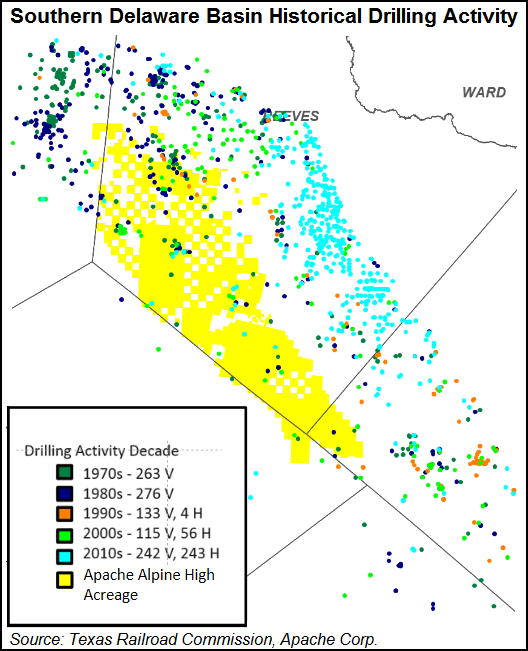

Last month Apache disclosed an “immense” find in southern Reeves County, which may hold more than 15 billion boe, including 3 billion bbl of oil and 75 Tcf of natural gas (see Shale Daily, Sept. 7). Alpine High lies in the southern corner of the Delaware sub-basin, a section of the Permian that of late has been stormed by producers seeking leaseholds.

The Alpine High, however, mostly has been bypassed because its rock layers were thought to be too fractured to support production and clay-filled. Apache geoscientists began looking into the formation in 2014 and found those assumptions were incorrect. To date the operator has drilled about 19 wells, with nine producing.

“This marks an exciting opportunity for our team to collaborate with an industry partner in an area with an extremely sensitive ecology,” said UTA professor Kevin Schug, who directs the Collaborative Laboratories for Environmental Analysis and Remediation (CLEAR) lab. “Through this partnership, we will be able to conduct a baseline analysis of both surface and groundwater quality in the area which will provide important data for future monitoring efforts.”

The Alpine High is in the parched Chihuahuan Desert on the outskirts of Balmorhea State Park, the world’s largest spring-fed swimming pool, sourced by the San Solomon Springs. The region’s restored desert wetlands, or cienegas, are home to endangered fish and other wildlife, and the springs provide an important source of water for area agriculture.

While some area stakeholders are fighting to prevent Apache from drilling, the company said it has no intention of drilling underneath the park. Apache said it “voluntarily decided to implement an exclusion zone and will not drill in or under Balmorhea State Park (an area where we have mineral leases) or in or under the city limits of Balmorhea.”

UTA already was looking for funding to study the region’s water quality when it was approached by Apache, Schug said. The university has not disclosed the amount of Apache’s donation, but Schug said it was enough to conduct a year-long review. The work is to begin in November and eventually would be published in peer-reviewed scientific journals. As to whether the research could be skewed by Apache, Schug said CLEAR had established itself “as neutral, independent and reliable.”

Working directly with Apache as the Alpine High is developed allows UTA researchers to track water quality and find ways to correct any issues, he said. The endeavor is an “unparalleled opportunity.” CLEAR isn’t working to “blow the whistle” on problems because that would not accomplish anything. Tracking water quality would be more holistic, and if an issue was found, UTA would work with Apache to fix it and show how it was fixed.

The Alpine High project is one of several by Apache to protect water resources in its onshore drilling operations. The company has in fact been recognized for its efforts in the annual reports, “Disclosing the Facts,” concerning hydraulic fracturing by As You Sow, Boston Common Asset Management and the Investor Environmental Health Network (see Daily GPI, Dec. 23, 2015; Nov. 8, 2013).

The Houston-based explorer developed a unique water-management system that uses brackish and recycled produced water to meet the water needs of its oil and gas activities in other areas of West Texas, and a similar program would be used at the Alpine High development.

Apache now works with Digital H2O and others to manage water recycling and reuse in the Permian (see Shale Daily, Oct. 28, 2015).

Digital H2O, whose initial focus has been on Texas plays, aggregates data about the onshore water of the energy sector and provides end-to-end water management in oil and gas production. Earlier this month it launched a second generation platform to provide proprietary data and predictive algorithms for exploration and production companies, oilfield service companies, and private equity firms.

“Our recent discovery represents a significant opportunity for Reeves County,” said Apache’s Cal Cooper, who directs special projects and emerging technology. “We are in the early stages of this project and want to take proactive steps to protect the sensitive ecology and water resources in the area. Our partnership with UTA’s CLEAR Lab will provide valuable baseline data as we work to monitor our operations and responsibly develop the abundant oil and natural gas resources at Alpine High.”

CLEAR has conducted many water studies in unconventional oil and gas plays. It recently found abnormalities in the drinking water in the Eagle Ford Shale in South Texas, (see Shale Daily, Sept. 26). Another study completed this year, which like the Eagle Ford research was published in the journal Science and the Total Environment, found that highly variable contamination events registered in and around unconventional oil and gas developments were the result of operational inefficiencies and not inherent to the extraction process itself.

Last year researchers at CLEAR confirmed that samples taken in 2013 from 100 drinking water wells within or near active natural gas wells in the Barnett Shale contained metals and chemical compounds at levels that exceeded federal limits (see Shale Daily, June 18, 2015; July 30, 2013).

CLEAR is “in a unique position to provide industry and the public with unbiased information about the potential effects of large-scale unconventional oil and gas development on the environment,” said UTA’s Frederick MacDonnell, who chairs the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry. “This is an example of where the university can support development of responsible energy extraction processes and the associated new technologies needed to improve large-scale industrial processes.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |