E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

U.S. Onshore E&Ps Eye Smaller, Strategic Deals, While Big Oil Brethren Look Overseas

Big Oil is throwing down investments worldwide to expand long-term reserves, while producers focused on the U.S. onshore have smaller, strategic dealmaking underway in the heart of the country, mostly in the Permian Basin and Oklahoma’s myriad, stacked reservoirs.

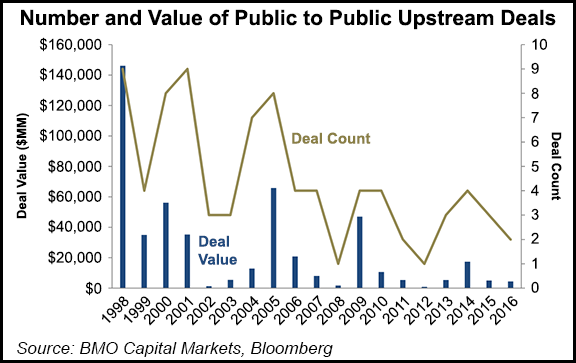

A spate of merger and acquisition (M&A) activity in the domestic onshore by the exploration and production (E&P) sector has been underway since the start of the year. However, a much anticipated wave of consolidation “has yet to play out” as producers have been more keen to recapitalize their beleaguered balance sheets than to add more leverage, said BMO Capital Markets analyst Phillip Jungwirth.

Valuation also has been another barrier to onshore M&A, “as core acreage was never devalued, while second tier properties were often burdened by elevated leverage, and we’ve yet to see a fairness opinion show an E&P trading at a discount to net asset value” on the New York Mercantile Exchange, Jungwirth said.

Overall, the market to sell assets by private and public E&Ps “remains relatively robust and valuations continue to surprise to the upside,” but many of the corporate deals appear to be motivated “by deleveraging and valuation multiple arbitrage, rather than the targets being long inventory and resource,” such as the Permian, which most had expected.

The recent stability in West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil and rising Henry Hub gas natural gas prices could prompt optimism for the second half of the year, with M&A likely to pick up in the Permian and Oklahoma’s stacked plays, according to S&P Global Ratings.

“The lack of confidence around the new floor for oil prices likely depressed the number of mergers and acquisitions in 2015, but there has been an upsurge in deal volume this year,” credit analysts said. M&A should accelerate during 2016, but don’t look for mega-deals. Recent transactions “suggest that small, strategic deals rather than corporate-wide M&A will dominate the market.”

New buyers mostly private-equity backed

The new buyers primarily are “private E&P companies, very often backed by private-equity funds,” and their “preferred targets” are the Permian and Oklahoma. M&A in the Eagle Ford Shale and the Williston Basin, still two of the three largest producers of unconventional oil in the United States, has been lackluster. “Operators there have been more focused on lowering costs and increasing efficiencies rather than expanding their asset base.”

Meanwhile, unlike independents and U.S. onshore-centric E&Ps, a big uptick in recent spend indicates that Big Oil is seeing sweet spots overseas and in the offshore.

In one of the biggest final investment decisions (FID) since oil prices crashed in late 2014, Chevron Corp. and its partners on Tuesday committed $36.8 billion to expand the Tengiz oil project in Kazakhstan, boosting production by 260,000 b/d.

The massive project “has undergone extensive engineering and construction planning reviews and is well-timed to take advantage of lower costs of oil industry goods and services,” Chevron’s upstream chief Jay Johnson said.

Tengiz would be the largest project launch in almost two years — and one of only nine major oilfield ventures to get an FID this year, according to Tudor, Pickering, Holt & Co. (TPH). Chevron owns a half-stake in the project while ExxonMobil Corp. owns 25%, and The field, in which Chevron owns a half-stake, has arguably been its “most profitable since it entered in 1993” and epitomizes “big fields getting bigger,” with proved reserves estimated at 2 billion boe unchanged from 15 years ago.

“Therefore it is no surprise that Chevron has opted to sanction a $36 billion project to maintain and grow production,” TPH analysts said. “We estimate that the future growth project will add 300 million bbl of proved reserves” based on a breakeven of around $50/bbl oil. At $75/bbl Tengiz is estimated to be worth more than $15 billion to Chevron.

The Tengiz announcement is an “inflection point” if only because it’s the first FID of $10 billion-plus in 2016, said Jefferies LLC.

The Big Oil money hopper is spinning for other operators too. BP plc with its partners pulled the trigger to add a third train at the Indonesian liquefied natural gas export project at Tangguh, which would bring total plant capacity to 11.5 million metric tons/year. ExxonMobil Corp. and Qatar Petroleum also are considering a partnership to buy stakes in Mozambique’s natural gas fields owned by Anadarko Petroleum Corp. and Eni SpA, Bloomberg reported Wednesday.

Since the price downturn, oilfield services costs have collapsed, sending prices for engineering and construction — and all of the parts involved — to lower levels. The FIDs and potential acquisitions couldn’t come at a better time.

In 2015, only four major FIDs were given the green light by oil companies, including in the Gulf of Mexico (GOM), Norway, Egypt and Ghana. And to date this year “just eight significant FIDs” have been announced, according to TPH. The decline in new projects suggests a “supply vacuum at the end of the decade.”

Global FIDs in 2016 primarily gas-focused

The FIDs this year mainly have been natural gas-focused, analysts noted. Projects include the Talos Energy LLC-operated Tornado facility in the GOM, Statoil ASA’s Oseberg Vestflanken field in Norway and Woodside Petroleum Ltd.’s Greater Enfield project in Australia.

“We estimate that combined, all the FIDs in the first half of 2016 will develop less than 500 million bbl of liquids,” TPH analysts said. In total, that’s “probably less than 5% of global oil output for the period,” but the FIDs would develop “almost 30 Tcf of gas.” Key FIDs still expected this year include BP’s Mad Dog in the GOM and Eni’s Coral floating LNG project in Mozambique.

Since the final quarter of 2014, global upstream development capital expenditures (capex) have been reduced from 2015 to 2020 by 22%, or $740 billion, according to Wood Mackenzie. Including reductions to conventional exploration investment, the figure rises to slightly above $1 trillion.

“The impact of falling oil prices on global upstream development spend has been enormous,” principal analyst Malcolm Dickson said. “Companies have responded to the fall by deferring or canceling projects, and costs have also fallen…In the nearer term, the impact is even more severe. Compared to pre-oil price fall expectations, capex will be down by around $370 billion, or 30%, in 2016 and 2017.”

More capex cuts are forecast throughout this year as companies struggle to get back on their feet.

“Virtually every oil producing country has seen some form of capex cuts,” Dickson said. “The deepest are in the U.S. Lower 48, where forecast capital investment has halved in 2016-2017, falling by $125 billion. This is mainly down to a big dropoff in drilling, with the onshore rig count dropping by 53% from 2015 to 2016.”

Upstream investment in Russia is expected to decline by 40% over the next two years, but most of the decline would be because of the rouble depreciating against the U.S. dollar. In the Middle East, less impact on spending cuts are expected as several countries spend to maintain market share. For instance, no decline is anticipated in Saudi Arabian investment in 2016/2017.

With the decline in investments, production will take a big hit. Wood Mackenzie is forecasting that 7 billion boe less will be produced between 2016 and 2020 than was expected before the end of 2014. In the near term, a decline of 3% in output, or 5 million boe/d less, is forecast in 2016, with 4%, or 6 million boe/d less in 2017. The U.S. onshore should take the brunt of the decline, accounting for 70% of the fall.

Deepwater spend suffering most

“In the main, discretionary projects have been hardest hit with conventional pre-FID greenfield investment alone down $80 billion from 2016 to 2020,” Dickson said. Deepwater fields have suffered the most, with spend on deep and ultra-deep projects reduced by nearly 40% in 2016-2017. Conventional exploration investment for 2015-2020 is $300 billion lower than forecast in 2014.

“Although exploration investment has more than halved since 2014, and the figure is expected to be around $42 billion per year for 2016 and the same in 2017, costs have not been cut as much and as quickly as we expected,” said Wood Mackenzie’s Andrew Latham, vice president of exploration research. “Some deepwater exploration spend has been protected by long rig contracts, but as these unwind we expect sharper cuts than in non-deepwater.”

Cost deflation has played a major role in driving down spend. For example, costs in the U.S. unconventional sector in 2015 fell by 25% on average from peak in 2014. Wood Mackenzie’s models show 2016 is likely to yield another 10% decline in costs.

“For now, the select few projects that are progressed will do so because costs have been cut substantially to hit economic hurdle rates,” Dickson said. “But kick-starting the next investment cycle will require more cost deflation and project scope optimization along with confidence in higher prices and arguably fiscal incentives.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |