Infrastructure | NGI All News Access | Regulatory

Long-Struggling Mackenzie Gas Project Gets Permit Extension

No construction promises and only a pledge to watch markets for signs of need were made when Canada’s frozen northern pipeline plan Thursday won a seven-year reprieve from dying due to weak natural gas and oil prices.

The National Energy Board (NEB) granted the Mackenzie Gas Project (MGP) a stay of execution until the end of 2022 (see Daily GPI, Aug. 28, 2015). The federal Liberal government’s cabinet in Ottawa has to co-sign the ruling to complete the permit time extension but shows no sign of balking.

The decision said, “The Board recognizes that the MGP is not economically feasible under current North American natural gas market conditions and is of the view that it will take many years for the market to recover. During this period circumstances may change.”

In a reply statement, senior MGP partner Imperial Oil added only, “This extension will allow time to assess whether changes in the North American natural gas market, including the potential impact of numerous proposed LNG [liquefied natural gas] projects, will result in improved economics for development of Mackenzie Delta gas reserves.”

The Northwest Territories government and a majority of commenters on the extension request, including Delta and Mackenzie Valley aboriginal communities, favored granting more time to the MGP consortium of Imperial, ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips and Shell.

Current thinking on the way to thaw the dormant project into action focuses on potential to incorporate arctic gas into a Pacific Coast LNG export terminal proposed by Imperial and ExxonMobil, with an added boost from byproduct liquids. The terminal is in regulatory stages, with no signs that the sponsors are in any hurry to start construction in the teeth of sagging overseas LNG prices.

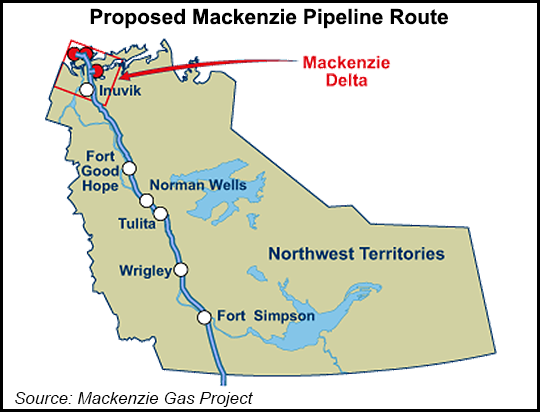

The C$16.2 billion (US$12.5 billion) MGP includes wells, field gathering pipelines and a processing plant on the Delta, a 1,200-kilometer (720-mile) gas mainline through the Mackenzie Valley, and a companion 600-kilometer (360-mile) conduit for liquid byproducts to the Norman Wells oilfield and the northern top of the Canadian oil delivery network.

Initial daily capacity of the system was pegged at about 1 Bcf of gas plus 35,000 bbl of liquids. The gas mainline was sized to increase shipments to 1.8 Bcf/d by adding compressors at a pace to be determined by demand for northern supplies. The secondary liquids line was designed to match capacity on Enbridge Energy’s Norman Wells Pipeline, to replace depleting production from wells drilled in the early 1980s.

The expiry date extension is the fourth life for an industrial mega-cat that has repeatedly stumbled over market and regulatory setbacks over the past 40 years.

The first life ended when a 1978 national inquiry recommended a 10-year construction moratorium to give northern native communities a chance to complete land claims agreements that would help define their rights to pipeline benefits. Deals were made and the MGP recognized them by including one-third ownership of its pipeline by an aboriginal partnership.

In the second life, a version of the MGP that was known as the Delta Project obtained a long-term export license for arctic gas in 1989 only to let it expire without filing a construction application due to a chronic Canadian surplus and price slump.

The third life began when the MGP group filed for a construction certificate in mid-2004. The application triggered a regulatory process that lasted until the end of 2010, long after new shale production glutted markets and gutted prices across North America.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |