Marcellus | E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Utica Shale

Consensus Clear For Appalachia: Expect Even More Dry Gas Production This Year

After nearly two years of contending with historically low commodity prices, a majority of the Appalachian Basin’s leading producers have retreated almost exclusively to their dry natural gas acreage, where low breakeven prices and prolific wells are being used to defend against the downturn.

In the nation’s leading gas basin, the move is no surprise. But it marks a shift away from touting natural gas liquids (NGL) growth and what was recently a balance for rigs that were spread more evenly across wet, condensate and dry gas fairways throughout Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia. The precipitous fall in oil prices that began in June 2014 and weighed heavily on the markets for ethane, butane and propane is not the only factor underlying the move.

Prolific wells, production beats, better economics and a desire to maintain momentum during the slump have all aligned to shape a trend that points to the likelihood of more natural gas production this year in a basin that’s saturated with it.

“What we’ve seen too in the third and fourth quarter, and I think what we’ll see in 2016 is these companies just continue to beat expectations. These wells are getting bigger, more prolific and the profiles are shallower in terms of declines than we had previously expected,” said Topeka Capital Markets analyst Gabriele Sorbara. “Gulfport, Rice, even Eclipse beat, there are a lot of companies that beat on the production profile. And they’ve shifted over the past year from the condensate, liquids and oily areas to the dry gas areas, because they’re getting better economics.

“That’s where activity is going to continue to focus,” Sorbara added. “We’re seeing 15-25 Bcf-type wells. As you move farther east, now even in Pennsylvania, you’re seeing these massive deep Utica wells. EQT, Consol, these wells could be 30-plus Bcf wells. Although they do cost a lot more, they’re deeper and require more equipment on site, I think you’ll see that trend continue, too.”

Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia have all reported either double- or triple-digit natural gas production growth in recent years (see Shale Daily, March 9a; March 9b; Feb. 22). Similar growth is expected this year with an elusive and high number of drilled but uncompleted (DUC) wells expected to come online before the numbers begin to flatten. But Sorbara said he expects operators to once again surpass expectations this year, especially given how the rig count has declined and capital budgets have been cut.

“You have a lot of companies spending a lot more than they should be,” he said. “Gulfport, Rice; they have the firm takeaway, they have hedges and the balance sheet to really continue to spend dollars and that’s what a lot of these guys are doing to maintain that organizational momentum, I would say, through 2016 to set them up better for 2017.”

A brief review of 2016 forecasts released by Gulfport Energy Corp., Rice Energy Inc., Consol Energy Inc., Range Resources Corp., Antero Resources Corp., EQT Corp. and Cabot Oil & Gas Corp. — which represents a sizable portion of Appalachian shale production — showed that all of the companies are guiding for anywhere from 2-34% production growth in 2016. Southwestern Energy Co. has forecast a 16% decline in its year-over-year gas output, which makes it an exception to the expectation for more natural gas production this year (see Shale Daily, Feb. 26a).

Antero, Range and Southwestern are all guiding for significant liquids production, as they have in the past, but they’re more established in the basin, with solid hedge books and firm transportation portfolios. Antero also has said that it’s currently limited on dry gas takeaway capacity in the Utica of Ohio and West Virginia (see Shale Daily, Feb. 26b). The other operators, however, remain firmly committed to dry gas.

“We too are focused on dry gas production this year,” said Consol Vice President of Gas Operations Craig Neal. “…We recently removed a wet pad that we felt in this price environment should be halted. We perform an economic analysis on each pad before we proceed, and in fact, are even performing an economic analysis on those that are close to a breakeven price that are in production. We do that on a monthly basis as well, just to make sure we’re maintaining free cash flows.”

To be sure, Appalachia’s wet and condensate windows are much narrower, compared to the areal extent of the dry gas patch. But only until recently, more operators were focused on balancing both dry and wet gas production. In 2014, for example, West Virginia’s natural gas liquids production skyrocketed, going from 626,246 bbl in 2013 to nearly 4.7 million bbl.

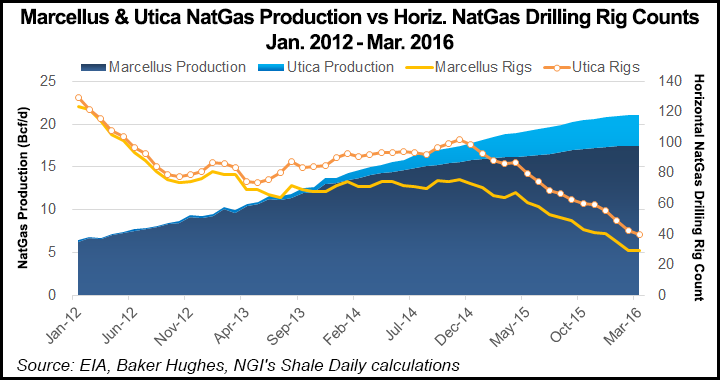

Speaking at an industry conference in Pittsburgh earlier this year, Seaport Global Securities’ Sunil Sibal, senior infrastructure analyst, said that despite the downturn, production from the Marcellus and Utica shales grew by about 5 Bcf/d between 2014 and 2015. Even as the market for gas continues to face strong headwinds, Sibal said the plays are both expected to add another 14 Bcf/d of production by 2020.

This past winter was one of the warmest on record, and it recently resulted in a collapse of New York Mercantile Exchange gas prices to their lowest levels since 1999. Bank of America Merrill Lynch said in a note to clients last week that storage was at its highest seasonal level ever. Declines “outside the Northeast,” the bank said, are now expected to drive down total U.S. production through the end of this year.

In the Marcellus and Utica, however, highly productive gas wells have flooded local markets and overwhelmed pipeline capacity, leaving trapped gas in the form of curtailments and DUCs. Nationwide, estimated natural gas well completions decreased 70% in 1Q2016, the American Petroleum Institute said this week. But the trend is particularly robust in Appalachia.

Incremental gas supply from the region, Raymond James said in December, will come from the trapped gas despite declining rigs and capital. The firm said it believes new pipelines set to come online in 2016 would unleash 2 Bcf/d of trapped gas. Various forecasts have said about 4 Bcf/d of new pipeline capacity is expected to become available this year in the basin.

“Unfortunately, the actual amount of trapped gas available to fill these pipes is a very nebulous and uncertain number,” Raymond James said. “Given the extremely large potential amount of DUCs and trapped gas in the region, the actual Northeast supply surge could easily be higher than we are currently modeling.”

Consol, for instance, has idled its drilling program indefinitely, but it’s still guiding for 15% production growth year-over-year. Neal said the company is being highly selective about which of its 102 DUCs to turn inline this year. While it has decided to turn 67 of them to sales, nearly all, or 57 will be dry gas wells. The other 10 wet wells are in the company’s Hess Corp.-operated area in Ohio.

Neal said dry gas production would account for a larger percentage of the company’s production profile this year, “just due to the fact that the turn-inlines will have less condensate production and less NGLs.” He added that if prices pick back up, the company would “promptly” return to work with a rig targeting dry gas.

“Right now, the first place we will likely put a rig to work will be in Monroe County, OH,” he said. “The market price there is slightly better, it’s a little shallower [compared to other Utica locations], so the drilling and completion costs are lower. And we do have that four well pad there that gives a lot of really good information,” he added of the company’s Switz pad, where it ran tests last year to learn more about the deep Utica.

EQT Corp. spokeswoman Linda Robertson also said “most of our wells will be drilled in dry gas areas this year.” The company has plans for 56 dry gas wells in Southwest Pennsylvania and West Virginia, along with another 21 wells in West Virginia that would be a mix of dry and wet.

Gulfport, Cabot, Consol and Antero have all said that they either have or plan to have a combined 243 DUCs this year. Gulfport is guiding for a production mix of up to 91% natural gas, Rice has said it will produce nothing but natural gas and Cabot has said the same, calling for 2-7% production growth this year, nearly all of which would be gas.

At the end of last week, there were 39 rigs running across Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia, down from 99 at the same time last year, according to Baker Hughes Inc. data. A majority of those were operating in known dry gas areas, such as Southeast Ohio, Northeast Pennsylvania and farther South in West Virginia, the company’s interactive map showed.

For a clearer picture of where operators in the basin have historically been focused, and where they’ve been operating more recently, see NGI’s new North American Shale & Resource Plays 2016 Factbook.

“I’m still surprised that we’ve seen the production growth that we have, that we’re still seeing,” said Ohio Oil and Gas Association Executive Vice President Shawn Bennett. “A lot of that is a testament to where everyone is focusing their attention with those rigs. It’s not the amount of wells that are continuing to keep production up, or the number of wells that are being drilled, it’s the quality of those wells and the efficiency and new techniques that we’ve learned from the reservoir here in the Utica.

“If the prices get better and ethane and propane markets improve, yes, you’ll see more activity start in the wet window,” he added. “In the meantime, even at these prices — these extremely low prices for natural gas — in some of these areas, where you get those monster wells, you can still turn a profit in the mid-$2 range.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |