What’s Shaking In Colorado? Professor Wants to Know

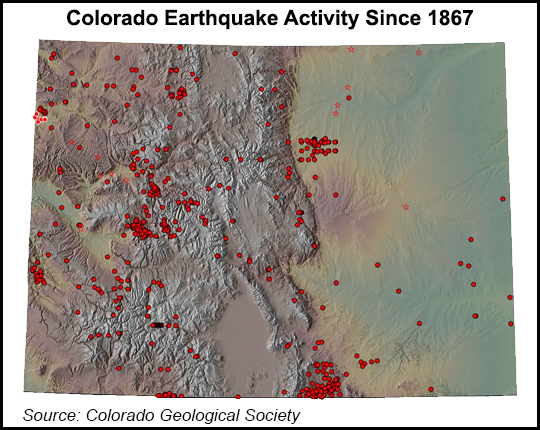

A state that helped pioneer research in induced earthquakes a half century ago, Colorado this month joined several other states with robust oil and natural gas exploration and production activity in trying to determine if the advent of small quakes is directly related to drilling.

Following a 3.4-magnitude quake that struck May 31 near Greeley, CO, in Weld County in the northeastern part of the Denver Julesburg (DJ) Basin, University of Colorado geophysics professor Anne Sheehan and a group of her graduate students have deployed five seismic measuring devices around the epicenter.

The stations will stay in place for up to two months, said Sheehan, who said there were some aftershocks within a few hours of the 3.4 quake before the measuring devices were put in place.

“So far, all we have seen are some small quakes of less than magnitude-1,” Sheehan said. “Hopefully, this was just a one-time event and was just a natural earthquake, but if it was induced, we certainly don’t want to have more of those.”

Sheehan said the work follows on the experience in tracking the role of E&P wastewater injection at well sites as part of an uptick of small quakes in Oklahoma, Ohio and Texas (see Shale Daily, May 6). Her impromptu monitoring project is focused on water (class 2) injection wells, which have also been the focus in other states.

“There have been cases in which fracking [hydraulic fracturing] has caused earthquakes, but it is very rare and it is only recently been documented in a couple of cases in Canada,” Sheehan told NGI‘s Shale Daily on Tuesday. “In Oklahoma, they think it might be fracking-related earthquakes, but usually it is tied to injection wells.”

The first work on induced quakes was done in the 1960s in Colorado related to deep water injection by the U.S. military at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal, Sheehan said. More recently, in the Paradox Valley in Colorado, there were some deep water injection-related quakes tied to a water reclamation project in the 1990s.

Sheehan said her intent is to obtain “good data that we can make available to everyone — the U.S. Geological Survey, drillers, the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission, etc.”

“If this does turn out to be related to injection wells in oil and gas, which we don’t know yet, then hopefully this data will help establish the guidelines and practices that can help reduce this sort of thing.”

Sheehan, who is part of a U.S. study group looking at induced earthquakes, said the ongoing work involves peers in Oklahoma and other places. “The USGS also has a number of scientists now that specialize in this issue,” she said.

In Oklahoma, the rate of earthquakes “has increased remarkably since October 2013 — by about 50% — significantly increasing the chance for a damaging 5.5-magnitude or greater quake in central Oklahoma,” the USGS and OGS said earlier this year.

Oklahoma’s previous annual record was set last year with 109 quakes, while the long-term annual average between 1978 and 2008 was two. All of that has been eclipsed in four months so far this year.

Sheehan also referred to a National Research Council study of “Induced Seismicity Potential for Energy Technologies” that came out two years ago. She attended a recent scientific meeting on the subject that the NRC sponsored in Golden, CO, recently (study).

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |