NGI Archives | NGI All News Access

Max Out U.S. Refining Before Lifting Crude Export Ban, Says Goldman

Retaining a ban on domestic crude oil exports until U.S. refineries reach “saturation” would be the optimal way to go, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. analysts said Tuesday. And the government should eliminate uncertainty over the ban’s future to clear the way for investment in refining capacity expansions.

“Once saturation is reached, it would then be optimal to lift the ban as value added from higher production outperforms value added from the refining sectors,” wrote analyst Damien Courvalin and his colleagues. “Importantly, keeping the export ban before saturation would deliver the highest value added to the U.S. economy.”

The benefits of crude exports, if/once they are allowed, would not last forever, the analysts said. The payoff to domestic producers and the economy would erode over time as higher production and exports led to lower Brent prices and declining profitability for the exploration sector.

In the meantime, policymakers should clear the air on whether/when the export ban would be lifted to stimulate investment in the refining sector. Capital spending on refineries is waiting in the wings for clarity on the ban, the analysts said. Stifling investment in refining is causing less value to be captured from production now and it means that the saturation point of the nation’s refining capacity may be reached sooner.

“This is important as our analysis shows that the highest value added growth would be achieved with the export ban in place but prior to saturation,” said analysts. “Further, even after the point of saturation is reached, value added growth is maximized if refinery capacity is highest.”

Even without exports, U.S. crude output from shales has stabilized global oil prices by decreasing domestic imports and raising petroleum product exports, the analysts said. “Going forward, we expect continued growth in U.S. shale oil production, combined with normalization in non-OPEC production growth outside North America to allow for a gradual decline in crude oil prices, with our 2015 year-end Brent price forecast at $100/bbl.”

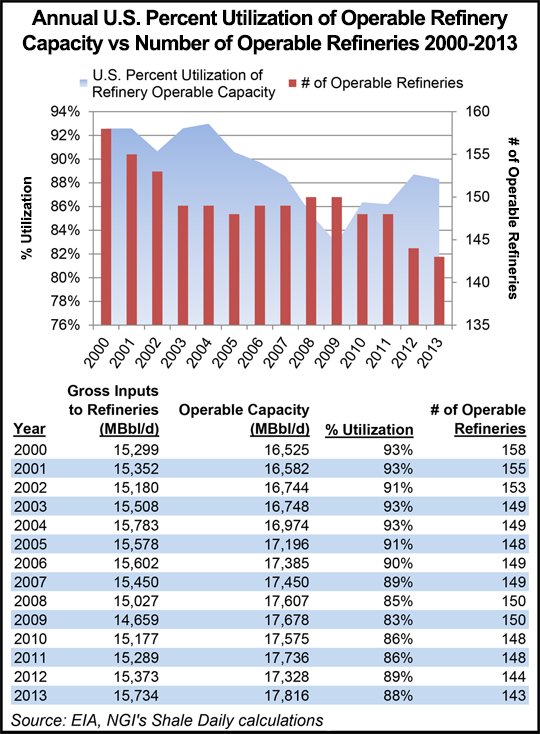

A medium-term risk to the outlook is the potential for the domestic crude market to reach saturation under the export ban as refining capacity could become insufficient to absorb production growth, or as discounted domestic crude prices slow production growth, the analysts said.

The export ban could weigh on U.S. production growth “in the next few years” at current extraction costs. “The uncertainty regarding when such saturation would be reached is significant as it is not simply a function of displacing imports but also depends on the pace at which domestic production will make its way to the East and West coasts, as well as to Canada, where refinery capacity is available and further import displacement can take place.”

Lifting or keeping the export ban generates tradeoffs in either case, the analysts said. Lifting the ban would stimulate domestic production to its highest levels, leading to lower prices for global crude oil and for U.S. transportation fuels. However, lifting the ban also “…would likely limit the incentive for U.S. refiners to expand capacity.”

On the other hand, retaining the ban would likely slow domestic production over the coming years and keep domestic crude trading “at a large discount” to global crude. In this scenario the upside would be “strong” refining capacity expansions that would support domestic crude production growth and export of products to the global market, the analysts said.

Last month, an analysis released by IHS Inc. said lifting the crude export ban would have far-reaching benefits economy-wide, including raising production, lowering domestic gasoline prices and creating nearly one million jobs (see Shale Daily, May 30).

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |