NGI Archives | NGI All News Access

Northwest NatGas Players Keep Eye on Methanol Projects

Amid flat near-term natural gas demand forecasts, the hydropower-dominated Pacific Northwest region and its principal gas stakeholders are keeping a sharp eye on two proposed billion-dollar gas-fueled methanol projects along the Columbia River in the state of Washington that surfaced this month.

Converting large quantities of natural gas into methanol for export to the Asian markets has far-flung economic and energy planning implications in a region that has been uncertain about future gas demand (see Daily GPI, July 25, 2013), and its major gas-related projects have been centered on two proposed liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects in Oregon (see Daily GPI, May 20, 2013).

Plans for twin gas-fueled methanol plants in the lower Columbia River region were unveiled with the hope of exporting production to China by 2018 (see Daily GPI, Jan. 23). One would be sited at Port Westward in Clatskanie and the other at the Port of Kalama in Kalama.

Northwest Innovation Works, which unveiled the proposals, is a venture created by China-based Clean Energy Commercialization Co., in turn a partnership of BP and the Chinese Academy of Sciences, along with private equity investors in H&Q Asia Pacific.

Those backers differentiate themselves from a number of other mega-sized energy export projects in the region, including the two LNG projects and major oil and coal export facilities in the southern and northern parts of Washington (Shale Daily, July 26, 2013).

Portland, OR-based NW Natural, the leading gas distribution utility in Oregon and the Vancouver, WA, suburban area of Portland, is in current discussions both with the methanol project backers and with Portland General Electric (PGE) regarding expansion of PGE’s Port Westward gas-fired electric generation plant, which is also close to the proposed Clatskanie methanol site.

“We’ve met with the Clean Energy Commercialization Co. from China,” a NW Natural spokesperson told NGI on Friday. “We have been meeting to discuss the possibility of providing gas transportation to them.”

NW Natural’s involvement would be limited to the Port Westward methanol plant, not the Kalama site, she said. “At Port Westward, we would transport gas to them off an existing pipeline we have there — the Kelso-Beaver pipeline — and that is just for the first phase of the project.”

The local gas utility would add compression to the K-B line and provide interruptible service to the methanol plant in its first phase. “We don’t have capacity to serve further phases, except we are still talking to PGE about building a new 15-mile pipeline from our Mist Storage to PGE’s Port Westward Unit #2 proposed generation addition.”

The new pipeline could potentially serve the methanol plant also, the spokesperson said. The added gas-fired power plant is still in the “planning/approval” phase. And the methanol projects are “very preliminary” at this point as far as NW Natural is concerned. The power plant proposal should be decided “very soon,” she said.

Local officials are saying the proposed methanol facilities could become the biggest single industrial investment by far in the lower Columbia River region in decades.

For at least one of the proposed LNG export projects — Jordan Cove along the south-central Oregon coast — the proposed methanol plants nearly 200 miles to the north don’t represent a direct threat or impact. “It is difficult for me to envision that they would have any impact on our permitting process,” said Bob Braddock, Jordan Cove project manager.

Regarding the proposed plants’ collective gas demand, Braddock said he would estimate it at 200 MMcf/d if each plant produced 2,500-3,000 metric tons/d of methanol. Those supplies would come through Williams’ Northwest Pipeline interstate line from Sumas, WA.

“Our supply comes from Kingsgate [WA, out of British Columbia] or Opal, WY, so I don’t see any impact on our gas supply as we draw from a totally different pool of supply sources.”

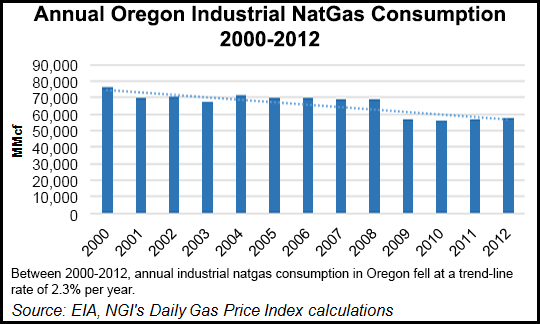

Between 2000 and 2012, annual industrial natural gas consumption in Oregon fell at a trend-line rate of 2.3% per year.

The other LNG project slated for a site along the Columbia River in Oregon proposes to link up with Williams’ interstate pipeline system in south-central Washington through an 87-mile connecting transmission pipeline. NGI contacted Oregon LNG CEO Peter Hansen for a reaction to the methanol plants, but he did not immediately respond to the queries.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |