Utica Shale | Infrastructure | Marcellus | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Permian Basin

Water Strategies Scrutinized as E&Ps, Midstreamers Look to Capitalize on Management

Appalachian producers trying to control costs in a low-price natural gas environment, along with their counterparts in the Permian Basin grappling with soaring production volumes, are more seriously thinking about water management in what could be a big opportunity for the midstream sector in the coming years.

Both produced and fresh water have historically been handled by exploration and production (E&P) companies as disposal or supplies are needed, with trucks handling the bulk of the work. And while pipelines have handled volumes to a varying degree in basins across the country, the midstream and upstream sectors are at work to expand that infrastructure and secure longer-term agreements for such services.

“Ultimately, the real win is to move as much water as possible in pipes, as opposed to trucking it, including impaired water,” said EQT Corp. CEO Rob McNally, who oversees the Lower 48’s largest natural gas producer. The company has been fending off a challenge from activist investors who want management and board changes. Part of management’s strategy to cut costs and maximize results is optimized water handling.

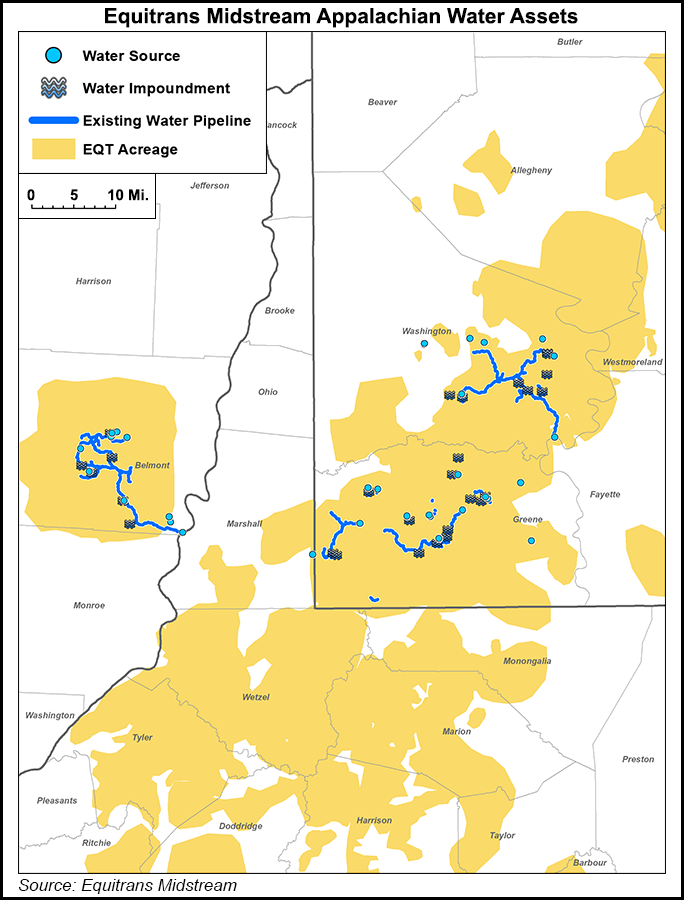

McNally said the Appalachian pure-play moves about 75,000 barrels of produced water each day, with about half of that volume being transported within a core area in southwest Pennsylvania. If EQT could pipe most of those volumes, he said, it could save about $5/barrel in water costs. The company has been in conversations about its water-hauling strategy with affiliate Equitrans Midstream Corp., which is crafting a plan that’s expected to provide growth opportunities as more Appalachian producers turn to pipelines for their water needs.

“We think a piped produced water business will be analogous in many ways to gas gathering, as there is a type curve of produced water that returns from the well,” Equitrans CEO Thomas Karam told financial analysts during a conference call earlier this year. “This creates a much more predictable cash flow stream that will facilitate long-term, fixed-fee contracts.”

Over time, wells steadily produce water. Volumes are higher initially and then decline. But they tend to remain higher than oil and gas production over the life of a well, opening the door for midstream companies to collect on a reliable source of output.

“The sense I get from these Northeast midstream companies is as gas prices are getting extreme pressure from things like associated gas in the Permian, they’re having to pull back on their growth expectations, so they’re looking for alternative ways to increase cash flow,” said Andy Ptacek, director of research at East Daley Capital Advisors Inc., when asked about growing interest in the water space. “I think that’s what’s driving a lot of it.”

While freshwater is a lumpier “one and done service” tied to the completion of wells, it could also provide additional opportunities, particularly for upstream operators, he added.

“Water is a sizable cost component of drilling and completion activity,” Ptacek told NGI’s Shale Daily. “Any time you can bring that in-house and capture that margin a third-party is charging you is a good thing.”

CNX Resources Corp., for example, is currently building a 24-mile water pipeline that would deliver 120 barrels per minute from the Ohio River in West Virginia to its Richhill area in southwest Pennsylvania that’s expected to be completed in 4Q2019. As CNX builds out those sorts of assets, they could also be dropped down to the company’s midstream master limited partnership.

“It is a great platform that reduces our lateral cost per foot, generates third-party cash flows and has significant growth opportunities,” said CFO Don Rush in April during a first quarter earnings call. “CNX is at the forefront of fresh and produced water services. Our infrastructure is already moving third-party produced water and will move more as water becomes a bigger issue and topic across the industry.”

According to CNX, the industry moves 4.5 million barrels of produced water each day in Pennsylvania alone. Recycling more of it would help cut costs for E&Ps. Appalachian pure-play Antero Resources Corp. in recent years opened one of the nation’s largest wastewater treatment facilities in West Virginia, estimating at the time the project was announced in 2015 that reusing the treated water in its operations could save up to $150,000/well.

More pipelines would have the added benefit of getting more trucks off the roads as well. Given the potential, Equitrans, the nation’s third largest gas gatherer, said it’s receiving interest from multiple producers as it hashes out a plan to expand water services in the Northeast that’s expected to be unveiled later this year.

“We don’t have to recreate the wheel, produced water is piped in other basins,” Karam said. “So what we’re going to try to do is introduce that to the Appalachian Basin with similar contractual characteristics.”

In drier areas, such as the Permian, where water infrastructure is more built-out than it is in resource-rich areas like the Northeast, the issue is still receiving an equal amount of attention. Sourcing and disposal in West Texas and southeast New Mexico is rapidly becoming one of the largest challenges to the Permian’s development.

Production is booming in the region. The Energy Information Administration expects oil and gas volumes to reach 4.2 million b/d and about 14.4 Bcf/d this month, respectively. The number of completed wells continues to increase. Wood Mackenzie expects water disposal volumes to double by 2022, stressing the current capacity and necessitating additional capital to expand water infrastructure.

As a result, water-related infrastructure deals in the Permian have been on the rise this year.

Private equity firm TPG Capital in March paid $930 million to take a majority stake in Goodnight Midstream, a produced water infrastructure company that works in the Permian, and the Eagle Ford and Bakken shales. Last month, NGL Energy Partners LP acquired Mesquite Disposals Unlimited LLC for $890 million. Mesquite has a fully interconnected produced water pipeline transportation and disposal system in New Mexico’s Eddy and Lea counties and in Loving County, TX, which would enable NGL Energy to expand its current system in the Delaware sub-basin of West Texas.

Also in May, private equity firm Five Point Energy LLC sold a minority stake in WaterBridge Resources LLC to affiliates of GIC, Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund, with both committing to fund the company’s growth opportunities.

More activity in the space driven by growing volumes is creating an opening for companies like WaterBridge.

“We are starting to see more signs of longer-term commitments from producers,” said East Daley’s Ryan Smith, senior director of commodity analysis, who tracks the Permian closely. “I still think a lot of these producers are not used to having to make commitments for water disposal, they’re willing to do that for oil pipelines because that’s their main product, but you kind of hesitate on making a long-term commitment on a waste product.”

WaterBridge recently acquired PDC Energy Inc.’s water assets in the Delaware for $125 million. That deal gives PDC long-term gathering and disposal rights on the assets.

Smith told NGI’s Shale Daily that the midstream industry is at a crossroads of sorts in the Permian as it tries to prove the multiples on water infrastructure that might be more attractive to bigger companies if the assets convincingly demonstrate profitability in the years ahead.

Ptacek added that the fact private equity is increasingly entering the water and disposal space shows that such firms are betting on large, diversified midstream companies stepping in once the model is proven.

“That’s their exit strategy,” he said. “They want to build that business up to get acquired.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |