NGI Mexico GPI | Infrastructure | NGI All News Access

Dos Bocas Refinery Approved in Latest AMLO Referendum

Mexico’s incoming government plans to build an oil refinery in the city of Dos Bocas, Tabasco state, following a public vote on the project last weekend.

Fewer than one million of Mexico’s 129.2 million people voted in the referendum, which included a total of 10 ballot initiatives proposed by President-Elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador. Each proposal passed overwhelmingly, the president-elect’s team said Monday.

The referendum included the Tren Maya railway project, which is expected to cost an estimated $6-8 billion, a separate train project on the Tehuantepec isthmus to connect the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, as well as a proposal to double senior citizen pensions.

The investment amount for the Dos Bocas refinery varies, with figures as high as $8 billion reported. During campaigning, the incoming president was unequivocal about his plans to develop the refinery, though it remains unclear if it will be carried out entirely by the national oil company, Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), or with partners. What is certain is that refinery projects by national oil companies are notorious for running over-budget and behind schedule.

Analysts and credit rating agencies have warned repeatedly that the refinery project itself and governing by referendum in general, bode poorly for investor confidence in the country and Pemex.

The vote comes just a few weeks after López Obrador said he would cancel a $13 billion international airport already under construction outside Mexico City, a decision that also was reached by referendum. The announcement to cancel the airport sent the values of Mexico’s currency and sovereign bonds tumbling.

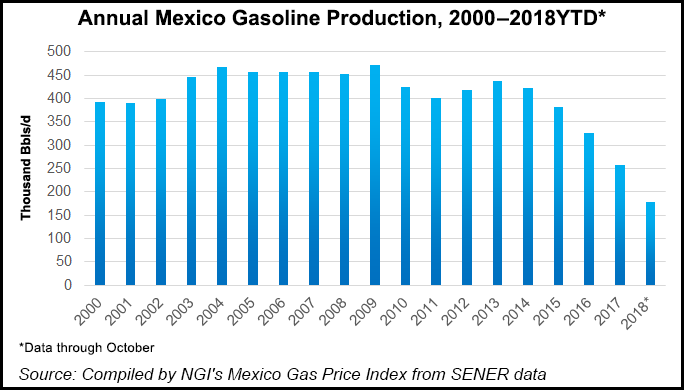

In addition to its negative impact on the local investment climate, the incoming López Obrador administration’s focus on revamping the refining industry is likely to exacerbate the country’s growing dependence on natural gas imports. Experts cite two main reasons: it will require billions in investments that otherwise could be directed to domestic exploration and production (E&P); and second, because the refining segment itself is a large consumer of gas.

Speaking earlier this month at LDC’s US-Mexico Natural Gas Forum in San Antonio, TX, the head of Mexico’s national pipeline grid operator Cenagas, Eduardo Prud’homme, said part of the reason why Pemex’s current utilization rates at the country’s six refineries average around 40% is because the company has had to ration declining associated gas output. Gas priority is given to industrial consumers.

“Pemex itself has scaled back its refining activity because there’s not enough gas for the whole country,” Prud’homme said.

Pemex accounts for about 22% of Mexico gas demand, according to Genscape Inc. senior natural gas analyst Rick Margolin. The E&P segment accounts for 60% of gas consumption, followed by petrochemicals (17%), refining (15%) and self-supplied power generation (8%).

Rising nationwide gas demand driven by the power sector and declining output from Pemex are trends that are expected to increase over the coming years.

As a result, piped gas imports from the United States, which surpassed 5 Bcf/d for the first time this year, are expected to grow by another 1.6 Bcf/d between 2018 and 2023, according to OPIS PointLogic analyst Warren Waite.

What’s less clear is the extent to which Cenagas, the National Hydrocarbons Commission (CNH) and the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE) will maintain their autonomy under the next administration.

“What is worrisome about Mr. López Obrador is that he does have a very complex relationship with institutions,” Tony Payan of Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy in Houston. He also spoke at the LDC event in San Antonio event.

“He thinks that the country ought to be run more like a pyramid, with the president on top,” Payan said. “He has this idea that the president is still at the center and that all the other institutions have to bend forward and backward according to the president.”

In a positive sign for the independence of the regulators, a bill to fold the CNH and CRE into the purview of the energy ministry Sener was shot down in Mexico’s lower house earlier this month. Still, there is concern that a meddlesome approach to governing could delay the maturation of the fledgling natural gas market, in which Pemex and state power utility Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE) are still the dominant players.

Beyond the question of financing, the Dos Bocas refinery also faces environmental opposition. Centro Mexicano de Derecho Ambiental (CEMDA), or Mexican Center of Environmental Law, earlier this month filed a complaint with oil and gas environmental watchdog Agencia de Seguridad, EnergÃa y Ambiente against Pemex. CEMDA said the Dos Bocas refinery does not have an environmental impact study and the project would negatively impact vegetation in the area.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |