Markets | LNG | LNG Insight | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Traditional LNG Contracting Tossed Overboard as Diverse Buyers, Sellers Take Helm

The traditional point-to-point model that has served the global liquefied natural gas (LNG) market for decades is quickly evolving as a diverse set of suppliers offer cargoes and more buyers are able to shop on their own terms.

The sellers market also is quickly evolving, upended in large part as Big Oil turns into Big Energy, building huge portfolios offering gas buyers equity or third-party contracted gas, experts said last month at Gastech 2019 in Houston.

Along with their differentiated portfolios, Big Energy suppliers have the trading chops to optimize prices and volumes, as well as the deep pockets to finance shipping and regasification terminals.

“The conditions required for traditional business models to succeed are disappearing fast,” said McKinsey & Co.’s Peter Lambert, senior expert in the oil and gas practice. The traditional, bilateral models are under fire, as the newer models put a bigger focus on commercial and trading capabilities.

Lifted in large part by growing U.S. LNG export dominance, a “persistent” global oversupply is giving buyers more bargaining chips and the well financed suppliers more clout.

Competition is expanding between LNG producers, portfolio players, traders and utilities, and the traditional LNG market model is becoming unsustainable, according to Lambert. Low-cost producers are competing with flexible portfolio optimizers, market developers and the focused incumbents.

Long-term contract-pricing mechanisms also are evolving in indexation and slope as the natural gas and oil markets diverge, putting pressure on buyers to reshape their contract portfolios.

Contracts now in place in Asia range between 13-14.5% slopes, but a move to current market rates of 11.5% would save roughly $15 billion a year, Lambert said. Slopes are the extent to which the LNG price changes in response to changes in the oil price. Buyers and sellers are protected from big price swings when long-term contracts have been indexed to oil under what is known as an s-curve.

When oil prices rise quickly, the s-curve allows buyers a slope when oil prices have reached a predefined level, at which time the price for LNG rises more slowly and with a time-lag. Buyers prefer a flat slope at high oil prices, while gas producers and sellers prefer flat slopes at low oil prices.

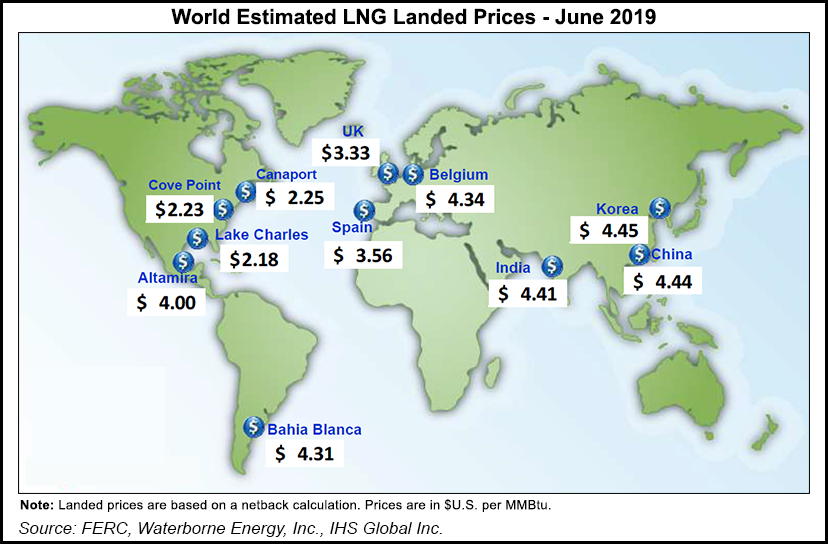

The market clearing price for LNG is pegged at around $7/MMBtu, which reflects the full cost of supply from U.S. projects, according to Lambert. A substantial amount of gas projects not yet sanctioned is below $7/MMBtu, using gas pricing shipped to the named port of destination (destination ex-ship) in Asia, as well as Qatar, Iran and Russia.

Market-based pricing is attempting to find its place, Lambert said. It typically takes more than eight years for full liquidity to emerge in any one market, as pricing tends to replace reference prices within two to five years, Lambert said.

For example, U.S. gas trading began in 1990. By 1994, there was a spot pricing de facto benchmark, and by 1998, gas hub liquidity had been established. The UK gas market, which began in 1996, established spot pricing by 1998, but it was 2006 before hub liquidity was established.

How long it takes for LNG to establish a global market remains uncertain. What is certain, however, is that the world needs substantially more investments in import/export infrastructure as demand is pegged to increase at a rate of around 3.6%/year from 2018 to 2035.

Determining how much investment is needed and where it is needed will be key for buyers and sellers, according to Lambert. Around 50 billion cubic meters of low-cost LNG projects still face major roadblocks, which means sanctioning for many projects still looking for contracts could be unlikely.

Still, unsanctioned LNG project sponsors are actively marketing their volumes, seeking larger and longer term deals, according to Wood Mackenzie’s Giles Farrer, director of LNG research. He also spoke at Gastech 2019.

“Until 2013, it was a long-term focused market,” Farrer said. “Over the course of the last three to five years, we’ve seen more medium-term and spot trade coming into the market,” with increasing market mobilization.

The size of deals has changed from “very large deals to certainly a lot of smaller deals,” which is a symptom of new buyers and importers emerging in the market. Some buyers are not taking the same sort of volumes as before on a shorter-term basis and are moving away from project-specific deals to more portfolio supply.

Oil-indexed contract prices recovered in 2018 driven by some “big deals” from Mozambique and Qatar to move gas into Asian markets, according to Farrer.

“The availability of Henry Hub-indexed LNG has created competition with oil-indexed contracts,” he said. “This sets a soft ceiling for oil slopes. But there also is a question around how much appetite there is for additional Henry Hub-indexed LNG among buyers.”

China is the largest potential market for additional Henry Hub-priced gas after it received its first direct sale and purchase agreement, or SPA, last year from U.S. LNG. Previously China had purchased Henry Hub-indexed deals from portfolio players.

One caveat in the dealmaking could be the U.S.-China trade war, as U.S. tariffs have created some uncertainty in the near-term, Farrer said.

There’s still quite a bit of the market shaking out, he explained. For example, India was an early mover into Henry Hub priced deals, but it has had to re-sell volumes to third-parties. India also is the most active country for tendering to buy spot/short-term cargoes.

Meanwhile, Japanese utilities are buying large LNG volumes from the initial LNG export projects, like Cheniere Energy Inc.’s Sabine Pass project in Louisiana.

“Declining LNG demand will limit additional contracts, but liberalization could create opportunities longer term,” Farrer noted.

Some buyers, including Tokyo Gas, are still signing Henry Hub-indexed deals. In Japan, the strategy has mostly been dependent on Korea Gas Corp., according to Farrer.

Some tentative sales agreements suggest there’s “some U.S. LNG appetite still there.” In South Korea, there’s been “strong interest in Henry Hub recently,” and China is believed to have “further appetite” for Henry Hub deals

“Consequently U.S. LNG sellers are looking to innovate in commercial structures and sales models to support additional projects,” Farrer said, echoing Lambert’s comments. “These new commercial models allow some buyers, producers, developers and investors to take different risks.”

A record number of LNG projects have been sanctioned this year, increasing supply post-2024. Final investment decisions (FID) this year include the ExxonMobil-Qatar Petroleum Golden Pass project underway on the Texas coast, along with Cheniere’s sixth train at Sabine Pass. Also reaching positive FID this year were Mozambique LNG, Russia’s Arctic LNG-2 and Venture Global LNG Inc.’s Calcasieu Pass project in Cameron Parish, LA.

Wood Mackenzie expects at least two more project sanctionings this year, Rovuma LNG in Mozambique by partners ExxonMobil and Eni SpA, as well as Woodfibre LNG, which would be built in British Columbia by Singapore-based Pacific Oil and Gas Ltd.

Oversupply is likely to increase before the market tightens again in the early 2020s, according to Wood Mackenzie. Another “weak cycle” begins in the mid-2020s before rebalancing by the latter part of the decade, Farrer said.

That aligns with general market expectations, according to NGI’s Patrick Rau, director of strategy and research. “The conventional wisdom had been that the global LNG supply/demand picture would come into balance somewhere in the 2023-24 timeframe, but now the consensus seems to be more like 2028-30. That’s a major shift,” he said.

The new liquefaction projects are going to increase the flexible supply within the oil and gas majors’ portfolios, Farrer said. “We expect the majors to target uncontracted LNG demand in the Pacific.”

At this year’s Japan Gas Forum, Wood Mackenzie asked conference attendees what their top priority in LNG contract negotiations was. “Volume flexibility,” the answer for 60% of the respondents, was far and away the No. 1 answer, followed by “lower oil slope” at around 25%. Inclusion of a gas index garnered about 10% of the answers.

Respondents, Farrer said, are also “looking to understand what’s happening with contract prices…” He predicted more pressure going forward to conduct price reviews, with buyers looking for more relief. Expect some contracts to go to arbitration, he said.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |