Infrastructure | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Reserving Natural Gas Capacity on Mexico’s Pipeline System Still Evolving

Editor’s Note: NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index, a leader tracking Mexico natural gas market reform, is offering the following column as part of a regular series on understanding this process, written by Eduardo Prud’homme. This is the fourth in the series.

Prud’homme was central to the development of Cenagas, the nation’s natural gas pipeline operator, an entity formed in 2015 as part of the energy reform process. He began his career at national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), worked for 14 years at the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE), rising to be chief economist, and from July 2015 through February served as the ISO Chief Officer for Cenagas, where he oversaw the technical, commercial and economic management of the nascent Natural Gas Integrated System (Sistrangas).

The opinions and positions expressed by Prud’homme do not necessarily reflect the views of NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index.

The ability to reserve transport capacity is relatively new in Mexico’s natural gas market. Up until June 2017, only state power company Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE) and a few users related to the electric sector were able to count on a guaranteed amount of daily space on the national pipeline system.

Firm reserve capacity has clear advantages both for users and owners of transport infrastructure. Users gain space on the pipeline, without the risk of capacity being usurped by others. This reliability gives certainty to any project that requires gas supply, while pipeline infrastructure companies are able to guarantee the recovery of their costs in a capital-intensive business. This service is thus a crucial piece to the development of new pipelines and the market.

The opening of the natural gas market in Mexico in 1995 was based on the notion that the ability to reserve capacity would be an option on the Sistema Nacional de Gasoductos (SNG) pipeline network, owned by a subsidiary of Pemex. The CRE was tasked with the process of opening capacity to third-parties in 1999, but given the complexity of the process, and the natural monopoly held by Pemex that could lead to discriminatory practices, the transition was put on hold until a level playing field existed for all players in the sector.

This transition ended up taking 18 years, all the way until pipeline operator Cenagas came into being.

At its inception Cenagas was tasked with managing the national pipeline system known as Sistrangas, which united all the many isolated pipeline systems into one. Cenagas as administrator of the capacity took on the task of coordinating flows so that natural gas could move from the border to the most remote corner of the pipeline system. This was only possible in the context of having an agent that didn’t market or consume gas, and whose sole interest was in coordinating flows, routes, and assigning capacity to users of the network.

Assigning capacity on a network with multiple injection and extraction points with flows in various directions across the country isn’t simple. It requires modeling that simulates adverse conditions, assuring reliable operation while responding to the mixed needs of users.

Given the growing importance of natural gas imports into Mexico, ownership and operation of cross-border pipelines is of utmost importance. The existence of nomination cycles north of the border, separate from those in Mexico, means that users with fixed capacity on cross-border pipelines don’t necessarily have capacity on Sistrangas. So, it becomes obvious that two differing systems need coordination so that gas gets to where it is needed, and this is also where Cenagas comes in.

Designing public policy to carry out open seasons or auctions for capacity on import pipelines was the first goal. Marketers and industrial users worried that they would be blocked at the point of entry into Mexico by the state companies given that they were the principal holders of cross-border capacity.

In February, 2017, Cenagas held an annual capacity auction for four routes along the pipeline leading to the Ramones project. Capacity on offer amounted to 753 Mmcf/d, and 30% of this was assigned to three companies. This was the precursor to the first open season on the Sistrangas.

For the first open season on the Sistrangas, prior to the process, and according to regulatory criteria defined by the CRE, Cenagas gave capacity priority assignments to Pemex and CFE for operations that were deemed strategic and of national interest. For example, Pemex refining and petrochemical operations were given reserved capacity, but Pemex marketing activities had to compete with other companies.

In the case of CFE, its power plants and those independent power producers (IPP) whose gas supply came from CFE were also given priority, but CFE’s gas trading activities were treated as capacity claimants like any other user.

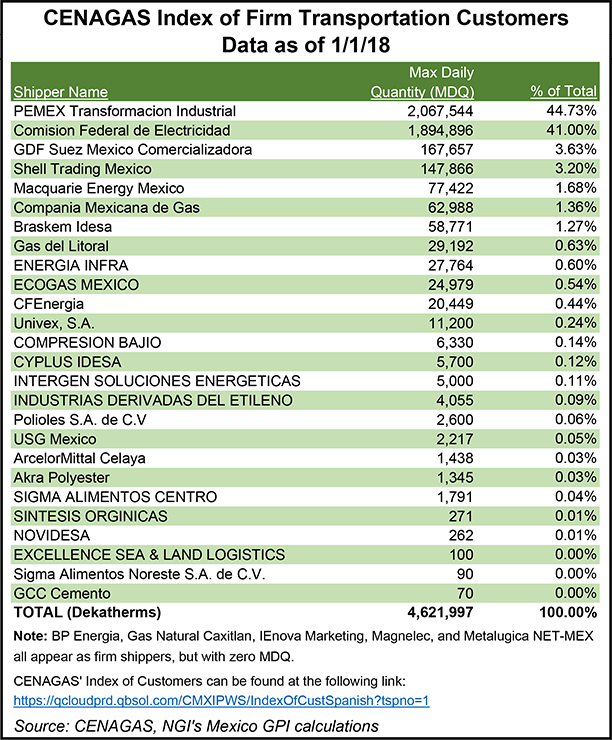

In the open season, Cenagas signed 37 one-year natural gas transport contracts on a firm basis ending on June 30, 2018. In addition, three contracts with state firms, three contracts with users that had investment agreements, four contracts with IPPs and four pre-existing contracts were honored, all of which were valid until June 30, 2018. In total, 6.3 Bcf of transportation capacity of natural gas on a firm basis was contracted out.

The aim of the one-year time frame was to give users the opportunity to get to know the new system, without having to commit to a longer-term agreement that would increase the transaction cost of reversing a contractual relationship. On July 1, 2017, the transitory phase — started in 1999 — was concluded to make way for a capacity reserve mechanism in Mexico’s natural gas market.

During that first year of reserve capacity, Cenagas launched an electronic bulletin board (EBB) in step with North American Energy Board practices. This made capacity and flows on the Sistrangas transparent. In the event of capacity being released, new availability would be announced by Cenagas and a replacement shipper could apply for it without going through the open season process.

In February 2018, Cenagas allowed users to renew or modify their natural gas transport contracts on a firm basis. Users were allowed to renew contracts on the Sistrangas without exceeding the maximum daily quantity originally contracted, with the only stipulation being a one year-minimum period. There was no maximum time table set. All shippers also were given the possibility of modifying primary reception points, if technically feasible.

Last month, Cenagas announced that companies with a firm contract valid as of June 30, 2019, would be again allowed to renew their capacity, as long as they gave notice to Cenagas at least three months before the expiration of the contract, in other words by March 30. Conditions were similar as those of the previous year, but with no mention of being able to modify reception points, nor details on minimum or maximum contract lengths. In the event a user wanted to release capacity, it was asked to notify Cenagas in writing.

Although the period to renew contracts was this year made shorter, the fact that it has taken place is a sign of continuity in the natural gas market, at least in terms of transport capacity already assigned. This fact alone should be well received by the industry. However, many questions remain regarding how capacity that has been released will be used.

According to the regulation in place, the released capacity should be auctioned in a future open season process. To date, there has been no notice of any call. An open season must be approved by the CRE. In the absence of an open season process, the available capacity must be advertised in the EBB and access to it made open as stipulated by law. This has yet to happen.

The issue is very important when considering maintaining system balance. It’s important to know for example if the newly available capacity can be used in new primary injection points, such as those connecting to pipelines that could increase flow in the Sistrangas, such as the connection in Montegrande with the Sur de Texas-Tuxpan pipeline, which would bring in gas from Waha in Texas.

It also has important implications for competition and tariffs, and the potential release of capacity assigned to the CFE on the different pipelines that have stalled and whose contracts have been much-talked about by the new administration.

In the event that CFE does release capacity, there is a new opportunity to improve competition in the marketing of natural gas and take advantage of bringing in gas from basins such as those in Texas that are now displaying negative prices. This capacity could even be used by Cenagas as a stop-gap measure to service all of its users including those suffering from shortages in the Southeast.

In sum, there are lots of questions, but there are also numerous opportunities available to achieve an ideal balance between natural gas market needs and the goals of strengthening Pemex operations. Let’s hope pragmatism prevails.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |