E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Southwestern Earning Higher Prices for ‘Responsibly’ Produced Natural Gas

A relative newcomer to the oil and natural gas industry may have found a way to monetize the upstream sector’s costly attempts to manage emissions and produce natural gas in a more responsible way using an asset rating system that could be applied to basins across the country.

Southwestern Energy Co. this month struck a deal with a New Jersey utility to sell gas at a premium to local Appalachian index prices. The contract was reached with New Jersey Natural Gas (NJNG) for volumes produced from a group of wells in West Virginia that were certified by Texas-based Independent Energy Standards Corp.’s (IES) TrustWell Responsible Gas Program. Terms of the agreement were not disclosed.

The novel ratings system relies on the company’s background in analytics to combine engineering expertise and a history of best practices with proprietary data and software.

“The way I got to this concept is I took the approach of where is the most growth and challenges to solve relative to the number of business models, entrepreneurship,” said IES CEO Jory Caulkins, who founded the company in 2014 as a graduate student at Stanford University. “What was the greatest opportunity to build something big, transformative and impactful? And the oil and gas space, in particular the upstream, it’s big; there’s a lot of challenges.”

Caulkins, who has established and sold other businesses, had little experience in the energy space. The company was born of the industry’s thirst for what differentiates a “good” operation from a “bad” one.

IES had its start in assessing industry risk for operators, insurance underwriters and investors. However, over the last year, TrustWell has been the primary focus. The program provides independent, third-party ratings for gas wells, or entire asset bases on a scale of 0-150 in an attempt to show buyers that the commodity is produced in the most responsible way possible.

However, the deal between Southwestern and NJNG may be more indicative of the shift underway in the energy space, where consumers are becoming aware of how their energy is generated and consumed with regard to high-volume hydraulic fracturing, climate change and what exactly constitutes “clean” energy. Consumers have more choices, and as renewables become more efficient, the market is taking notice. In a sign of that shift, the entire oil and gas supply chain has increasingly promoted corporate responsibility and sustainability initiatives.

NJNG, a subsidiary of New Jersey Resources (NJR), serves more than 525,000 customers across five counties in a state where environmental groups are growing more vociferous and echoing their counterparts in New York, where fossil fuels have faced staunch opposition. Under Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy, New Jersey has rejoined the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, resisted gas infrastructure and is aiming to use 100% renewables by 2050.

Reducing Carbon Footprints

NJR spokesman Michael Kinney pointed to efforts to reduce the company’s carbon footprint as a reason for striking the deal with Southwestern for IES-certified gas, saying the move takes the sustainability efforts to the “next level.” The utility already buys 100% of its electricity from the New Jersey Clean Power Choice Program, has energy-efficiency programs in place to help customers save and conserve, and has made emissions reduction a strategic priority.

“I think it is part of a general trend toward focusing on sustainability and demonstrating the sustainability of our product, natural gas,” said the American Gas Association’s Pam Lacey, chief regulatory counsel. The trade group represents more than 200 gas utilities across the country.

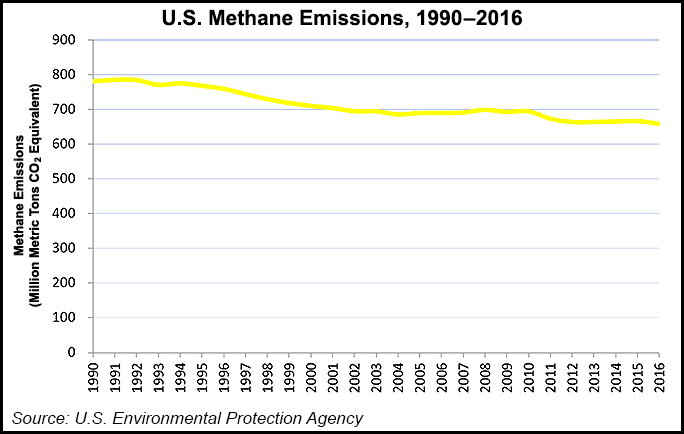

Emissions from distribution systems nationwide have dropped precipitously since the 1990s, Lacey said, when the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) rolled out the Natural Gas Star Program, which encourages industry players to voluntarily improve efficiency and cut pollution.

“In that way, it’s not new, but now we’re talking about it with new words,” Lacey said. She acknowledged that a shifting energy marketplace has created a “growing sense of corporate responsibility” across the industry.

NJNG plans to now source 14% of its gas supply from Southwestern’s rated wells in West Virginia, Kinney said. In addition to quantifying the amount, Caulkins said the ratings system was something akin to renewable energy credits that certify energy is generated in a credible way.

Southwestern spokesperson Jennifer Stewart said the company was intrigued by the IES model not only because the ratings system aligns with “what we consider important,” but because the concept allows it to “pursue tangible, monetary value from Southwestern Energy’s approach to environmental stewardship, including methane emissions management, well integrity, water management, and chemical management and disclosure.”

More Deals Expected

IES has so far worked with about 30 producers, Caulkins told NGI. It acts as an intermediary with producers and gas buyers to get assets rated and contracts off the ground. More deals are expected in the coming months. Ultimately, the goal is to establish a standard for third-party verifications in the upstream sector, expand the market and provide ratings services rather than facilitate deals, he said.

“The rate limiting factor here is not going to be the producer, it’s going to be how quickly the utilities sign-up and kind of pull through the demand for it,” he said of establishing a stronger standard and growing the business.

The TrustWell system evaluates a wide range of impacts and risks, with a focus on four main categories that include water, air, land and community. Within each category is a range of topics covering, among other things, emissions and methane, leaks and spills, well integrity, water sourcing and community and engagement.

Over a process that can take anywhere from weeks to months, ratings are reached in three steps and can be renewed annually. IES charges a flat fee for certifications.

First, a profile is created for the asset and its location that establishes what the risks might be for a high-tech unconventional well in a place like Pennsylvania or an older, vertical well nearing the end of its producing life somewhere in Texas. Next, IES assesses how the company is managing its risks, using a “control system rubric,” or a library of sorts that consists of hundreds of different practices that the company’s engineers have compiled over the years.

“Instead of telling them this is what we have to do, we ask them to tell us what they’re doing and we’ll map that into our library, and we can score it from there,” Caulkins said.

Data compiled in the first two stages is rolled into an overall score for the four categories of water, air, land and community.

NJNG’s purchase of Southwestern’s rated gas was not the first time a buyer has sought out volumes certified by a third party. In addition to the EPA’s Natural Gas Star program, and others initiated by the agency, there are various programs. Late last year, for example, the American Petroleum Institute launched the Environmental Partnership with 26 major oil and gas producers to develop three separate programs to enhance leak detection, replace equipment and curb emissions.

Some of the efforts have failed to gain traction. In 2014, the Center for Responsible Shale Development began taking applications for Appalachian operators to be certified against a robust set of standards during a costly audit that could take up to six months. After two years, however, the center has certified four operators. Its executive director stepped down earlier this year and a consultant now is developing a long-range plan.

Caulkins said the IES approach is scalable and capable of providing a comparison of responsible production from basin to basin. He also said IES has worked in every major producing-region of the country.

“If you come up with a checklist of ”here’s five things of what you must do to get a binary pass or don’t pass certification,’ that just doesn’t scale beyond a small piece of the market and therefore is really not that valuable, especially if consumers of that information are trying to compare one thing versus another in an apples-to-apples way,” Caulkins said, noting the disparities that exist between plays across the country.

Skepticism An Obstacle

Caulkins admits, however, that skepticism in TrustWell is an obstacle. Upstream executives have told him they don’t need a third-party verification as they already are putting time, money and effort into emissions controls and safety measures.

“This is not an additional cost; it’s actually a way to get a return on investment for a lot of those efforts through premium gas,” he said, adding that the way a producer views its operations might be different from how a buyer views them. If they’re spending all this time money and effort on having top-notch operations, historically they really haven’t had a way to get a return on investment in many ways. This is a very powerful and concrete way to get a return on that investment.”

Exactly how much of a premium Southwestern is receiving for the rated gas is unclear. Stewart said she couldn’t discuss the commercial details of the agreement. Kinney said the gas is coming at no significant difference in cost for NJNG’s customers.

Environmental Defense Fund’s (EDF) Mark Brownstein, senior vice president of energy, whose organization participates in the IES Cooperative Stakeholders Program, said “methane emissions and other environmental problems threaten the viability of natural gas in a competitive energy landscape, where consumers have choices and expect energy to be both cheap and clean.” Certification is not a substitute for regulation, he added, but EDF expects “more companies coming forward to differentiate themselves through third-party assessments.”

In another show of the resistance the IES model faces, EDF is not participating in any effort to market natural gas as “green” or “responsible,” even though it’s participating in the stakeholders program. That viewpoint is held by others in the environmental community that might resist accreditation efforts, regardless of their effectiveness. Instead, EDF views its role as helping to reduce the environmental impacts of oil and gas production while the market transitions to alternative sources of energy.

EDF has also made clear over the years that voluntary efforts throughout the oil and gas industry can play a complementary role in improving operational practices, but they are not a substitute for strong regulations or the renewable energy transition.

That’s where Caulkins sees the need for improved third-party verifications.

“Whether it’s good or bad, the industry is in the position of having to prove themselves just given the amount of public scrutiny that’s been placed on it, whether it’s merited or not,” he said, adding that the precedent Southwestern’s deal has set is in differentiating the commodity and earning more for it as a result. “That’s a very powerful symbol of where the market is going.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |