Suspension of Mexico Oil & Natural Gas Bid Rounds Could Lead to ‘Missed Opportunities’

Suspension of oil and natural gas bid rounds by Mexico’s next government could lead to missed opportunities and cause drillers to look elsewhere to grow their portfolios, according to a local expert.

“I think we’re all struggling to [determine] what is a signal and what is noise,” Pablo Zarate of the Pulso Energético think tank told NGI’s Mexico GPI in reference to reports that President-Elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s government was considering postponing or suspending tenders scheduled for 2019 and beyond.

Zarate highlighted that López Obrador’s transition team has yet to publicly confirm the accounts. Nonetheless, the president-elect’s top energy advisors have been critical of the 2013-14 constitutional energy reform that made competitive bidding processes possible, and are currently reviewing the 105 contracts awarded through bid rounds to date for “anomalies.”

And while the outgoing and incoming governments share the objective of reversing a rapid decline in oil and gas output, they have starkly different visions of how this should be achieved.

Current President Enrique Peña Nieto has courted private capital through open bidding processes, overseen by national hydrocarbons commission CNH, for new acreage and for joint venture stakes with national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex).

López Obrador’s camp, meanwhile, has made clear that it intends to address the country’s production and energy security woes by increasing Pemex’s exploration and production (E&P) budget and giving the state-owned behemoth more leeway to select its own joint-venture partners.

But regardless of the size of Pemex’s budget or any additional autonomy it may gain, further delays to the scheduled bid rounds could nonetheless jeopardize production growth in the country, according to Zarate.

“I think that one way to look at it is that Mexico used to have one engine for its production, and that’s Pemex,” said Zarate, who is Pulso Energético’s director of information. “And what the reform did, is it started three engines: kind of a hybrid between Pemex and the industry, Pemex by itself, and the rounds, which are kind of a third engine that’s showing some good results. And I think that if what you want to show is rapid results in terms of stopping the decline in production and potentially overturning it, you should consider keeping all three of those engines going, and [keep them] going at capacity.”

Two bid rounds for oil and gas blocks and a tender for operating stakes in licenses held by Pemex remain on the calendar for February 2019, following their postponement from the originally scheduled date of September 2018.

However, Reuters reported Tuesday that López Obrador was considering the indefinite suspension of bid rounds, citing a policy document leaked by his transition team and corroborating earlier stories by other outlets.

In a livestreamed interview conducted Monday by Zarate and Manuel Molano of the Instituto Mexicano para la Competitividad, Fluvio RuÃz Alarcon, who is expected to lead Pemex’s E&P division under López Obrador, did not address the possible suspension of rounds.

He did say, however, that he supports modifying the reform’s secondary laws to strengthen Pemex and give it more autonomy to choose its partners.

“One of the most important instruments of the energy reform was the possibility that it gave to Pemex to establish alliances with other oil companies, particularly in the case of Pemex Exploración y Producción [PEP],” RuÃz said in reference to Pemex’s E&P unit.

However, he continued, “I consider that this tool will be much more powerful if it allows Pemex on its own to make the selection of its partners because then you can establish synergies of many types.”

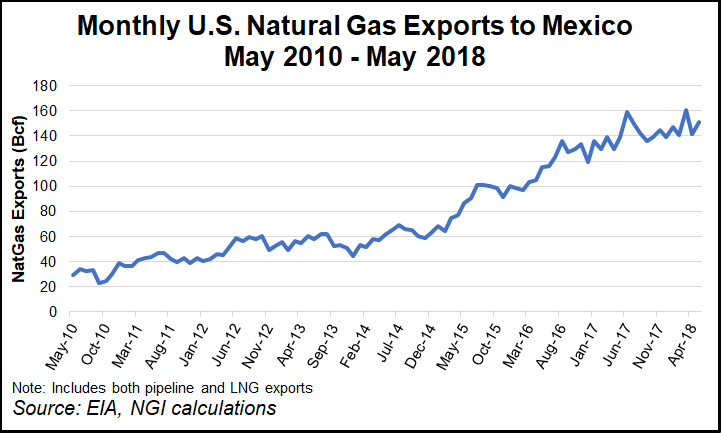

RuÃz, a close ally of López Obrador and former Pemex board member, also said he would like to see the law modified to allow PEP to seek upstream opportunities outside of Mexico, and that reducing dependence on natural gas imports from the US is critical, even more so than substituting imports of gasoline.

With regard to the suspension of bid rounds, Zarate said the potential consequences go beyond the simple arithmetic of delaying rounds by two, four or six years.

“It’s not the same thing to produce your oil resources right now as it is to produce them two years later,” said Zarate. “You lose money by waiting.”

What’s more, Zarate said, “The way the international oil and gas industry is set up, you need to be able to keep going at regular rhythms to attract investments from year to year. And if you don’t provide continuity … then opportunities can be missed. And if those investment opportunities are missed, that means that the resources will not be developed, or will not be developed in a timely manner.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |