Markets | Infrastructure | NGI All News Access

Mexico’s LNG Needs Seen Gradually Diminishing as Pipelines Come Online

The role of liquefied natural gas (LNG) in the Mexican supply balance is set to evolve after several pending pipelines come in-service later this year, experts say.

A handful of delayed projects that would connect gas consumers in northwest and central Mexico to U.S. producers in the Permian basin are due to wrap up by year’s end or early 2019. The 2.6 Bcf/d Sur de Texas-Tuxpan marine pipeline, running from South Texas to the Mexican port of Tuxpan, is also scheduled to come in-service later this year, as is the 600 MMcf/d Nueva Era pipeline in Nuevo Leon state.

“We expect that LNG dependency will decline at a more rapid pace once those pipelines can deliver more U.S. gas to the center of the country,” Wood Mackenzie research analyst Rodrigo Rosas told NGI’s Mexico GPI. “By 2023, we see LNG playing a relatively small role in the energy matrix.”

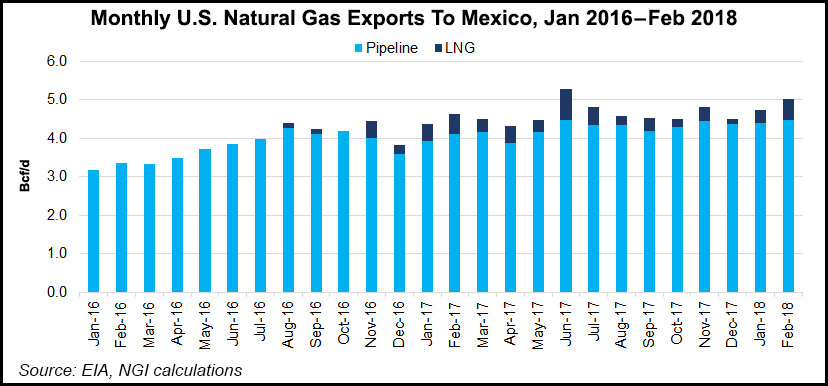

LNG supplied 713 MMcf/d or 9.1% of Mexico’s natural gas in February, according to the latest data from the Energy Ministry (Sener). The supply share was up both year/year and sequentially, although it was down from a recent peak of around 10.7% in August and September.

Mexican LNG supply averaged 700 MMcf/d in 2017, compared to 527 MMcf/d in 2016 and 721 MMcf/d in 2015, according to the Sener data. The average annual supply share was 8.8% in 2017, 6.7% in 2016 and 9.5% in 2015.

Social protests and legal challenges have held up several of the northwest Mexico pipelines located downstream from the U.S. border. These projects would mainly supply power plants operated by state electricity company Comision Federal de Electricidad (CFE) and its independent power producers.

Once those pipelines are completed, however, cheaper land imports are expected to further displace LNG in the Mexican gas market.

“With supply set to increase in the Permian basin and greater capacity to import natural gas via pipeline, it will be challenging for LNG facilities to compete with that reality,” Adrian Duhalt told NGI’s Mexico GPI. He is a postdoctoral fellow in Mexico energy studies at Rice University’s Baker Institute.

“Another factor to take into account is that many of the pipelines in northern Mexico have been promoted by the CFE, which sources its gas from CFEnergia,” a fuel marketing affiliate, Duhalt added. “Once these CFE-promoted pipelines become operational, it will make sense for CFEnergia to maximize their use and economic advantages.”

Mexico has built three regasification terminals to date, although only two are currently active. The first of these terminals — the Altamira facility, located on the Gulf Coast of northeast Mexico — came online in 2006.

“With population growth and economic development leading to strong growth in electricity demand, LNG emerged as a cost-competitive option,” Rosas said. “CFE started an important reconversion program, moving from fuel oil to gas-fired plants, requiring vast amounts of gas. With the shale revolution still not in the sight at that time, LNG played an important role.”

The subsequent unconventional boom in the United States, along with surging LNG demand in Asian markets, has caused demand to all but dry up at one of the Mexican terminals, Energia Costa Azul (ECA).

Located in Baja California state on the Pacific Coast, ECA has not supplied gas to Mexican consumers since around mid-2016. Its owner, a local subsidiary of Sempra Energy, is now evaluating a liquefaction project for exports to Asian markets.

The other Pacific Coast regas terminal, Manzanillo, located in Colima state, has operated at or near full capacity for most of 2017 and into this year, supplying 540 MMcf/d in February.

A consortium of Korea Gas Corp. (Kogas), Mitsui & Co. Ltd and Samsung owns the terminal, which started operating in 2012. It is indirectly connected to Mexico’s main transmission system, the integrated Sistrangas network, through the 860 MMcf/d Guadalajara pipeline.

Altamira supplied 173 MMcf/d in February, operating at around 25% capacity. The terminal, owned by Dutch company Royal Vopak NV and Spain’s Enagas SA, injects gas directly into Sistrangas pipelines running through the northeast state of Tamaulipas. Most of Mexico’s pipeline imports, from South Texas, flow through this region of the country.

CFE has supply contracts to receive LNG from the two active LNG terminals. In recent years, Mexico has sourced much of its LNG from Peru, along with several Asian and African countries, but this is changing with new market developments.

Mexico has been the largest destination for U.S. LNG exports since the Sabine Pass terminal in Louisiana began operating in February 2016, according to the EIA. Altamira is well positioned to receive cargos from Sabine Pass and other U.S. export facilities planned along the Gulf Coast.

Manzanillo, in turn, has historically received shipments from Peru, but “deliveries from Sabine Pass to Mexico’s two Pacific Coast terminals… were made far easier (and cheaper) by the recent expansion of locks along the Panama Canal, a project completed in June 2016,” RBN Energy LLC analyst Housley Carr noted in a recent blog post.

Although it is likely to diminish, LNG should still have a role to play in Mexico’s gas supply over the near to medium term.

CFE and state oil company Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex), for example, have announced plans to rent a floating storage and regasification (FSRU) unit off the coast of Veracruz, to help ease gas shortages in southeast Mexico. Bidding documents for rental and supply tenders have yet to be issued.

The existing LNG terminals can also act as a short-term palliative for demand fluctuations, until Mexico develops large-scale storage facilities. Altamira and Manzanillo can each store 300,000 cubic meters (10.6 MMcf) of natural gas.

“Occasional volumes should arrive until storage capacity is developed as Sistrangas uses it to keep optimal operating conditions,” Rosas said

In fact, the Energy Ministry recently released a public policy document to promote the development of underground gas storage that also included a requirement that the Sistrangas operator hold inventories at Altamira and Manzanillo for system balancing.

The inventory requirement may be lifted once Mexico builds 45 Bcf of strategic underground storage, which is supposed to occur by 2026 at the latest, according to the policy.

The system’s operator, the Centro de Control del Gas Natural (Cenagas), was already using LNG for balancing before the publication of the storage policy. LNG balancing costs were transferred to all Sistrangas users until around mid-2017, when Cenagas began passing on the costs only to those shippers that caused the system to become imbalanced.

Beyond these balancing costs, LNG can also impact gas prices in the regions adjacent to Mexico’s regas terminals. The Comision Reguladora de Energia (CRE), the energy regulator, has divided the country into six trading zones and started reporting regional prices earlier this year.

“A clear effect of a $1.57/MMBtu premium to Henry Hub in March is seen in CRE’s Region 4, where the Manzanillo LNG terminal is located,” Rosas said. “Those prices are a volume-weighted average, which reflects piped, domestic production and LNG transactions in each region.”

CRE reported an average price of 75.401 pesos/gigajoule (GJ), or $4.258/MMBtu, for Region 4 in March, compared a national average of 68.855 pesos/GJ ($3.888/MMBtu).

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |