Markets | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Raymond James Cuts Natural Gas Price Forecast, Suggests $2.50 Needed to Balance Market Long-Term

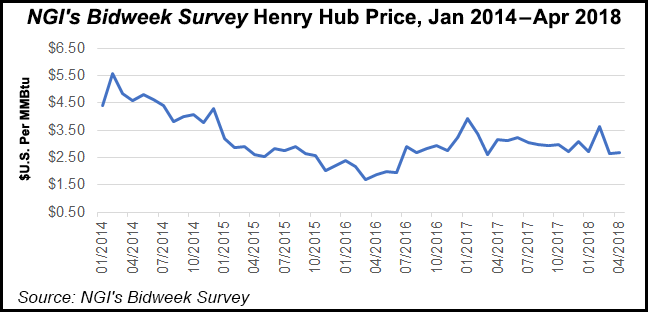

The overall picture for U.S. natural gas demand is healthy, but the onshore supply surge, particularly from associated gas, should more than cancel out strong demand growth, and a lower price is needed to balance the market over the long-term, according to Raymond James & Associates Inc.

“Given the high degree of associated gas production generated by some of the largest shale oil plays, U.S. natural gas prices have effectively become inversely related to oil prices,” said analysts J. Marshall Adkins and Pavel Molchanov in a note Monday.

“The bottom line is that we are maintaining our 2018 U.S. gas price forecast of $2.75/Mcf, but lowering 2019 from $2.75 to $2.25. Longer-term, we now think $2.50 is more reasonable than $2.75.”

The lower price is forecast in part because associated gas should remain strong in 2020 and beyond. To balance the markets, prices would need only “modest” supply growth from Appalachia, with declines possibly in other onshore gas plays.

Natural gas inventories have reached their lowest level since 2014, but it’s no time to be bullish on prices, the duo said.

“As higher oil prices spur growth in oil production, they also drive an increasing supply of associated gas. Put simply, the better things get for oil prices, the worse the read-through for gas prices.” Ironically, the lower forecast for future gas prices is coming despite “very strong” demand growth, analysts said.

U.S. demand remains stout because of coal-to-gas switching, petrochemical expansions, liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports and Mexico exports, according to Raymond James. However, demand appears “slightly weaker than originally modeled, mainly due to slower assumed expansion in LNG exports.”

In addition, the 2019 market now appears around “2.5 Bcf/d looser (i.e., more bearish) than originally predicted. Therefore, gas prices must fall sufficiently in 2019 to incentivize incremental fuel switching out of coal into gas, thereby balancing the market (i.e., ending the season with appropriate storage levels).

According to the analyst team, coal-to-gas switching demand needs to increase by 1.8 Bcf/d year/year, which would require prices to decline to $2.25/Mcf in 2019.

It may feel like a “war on coal” by the coal industry, “but government policy has nothing to do with it — this is pure Economics 101.”

Raymond James analysts are projecting a 3 Bcf/d year/year increase in associated gas supply growth this year and in 2019.

During the first three months of this year, U.S. drilling activity slightly outpaced the Raymond James model, with 966 actual rigs versus 955 forecast, with the biggest increase in the Permian basin with 46 more rigs.

“The Permian alone should provide as much as 5.3 Bcf/d of gas production growth by 2020,” according to Adkins and Molchanov. “Additionally, gas supply uplift from the Eagle Ford Shale — 1.8 Bcf/d from 2017 to 2019 — is also substantial.”

Enhanced completions, characterized by increased proppant loads, are driving improvement in gas well economics in many basins.

“All in, we now project a massive U.S. gas supply growth of 7 Bcf/d in 2018 and 6 Bcf/d in 2019 — for a whopping 13 Bcf/d in just two years!,” they said. “U.S. natural gas demand is looking mostly healthy in 2018/19, but slightly less-than-expected due to some LNG project delays.”

The top negative variable on the demand side continues to be wind and solar penetration, which is reducing the gains made by natural gas in the electricity mix.

Raymond James is forecasting U.S. LNG exports of 3.1 Bcf/d this year. However, analysts have reduced their 2019 LNG growth assumptions to reflect the delay in Freeport LNG’s startup until the second half of next year.

“So far, the ramp-up of various LNG projects are taking slightly longer than expected,” said Adkins and his colleagues. Startups next year should include Freeport, along with Sempra Energy’s Cameron LNG project in Louisiana and Cheniere Energy Inc.’s Corpus Christi terminal in South Texas.

However, the first “steady-state year” for all of the LNG export facilities with a total of 9-10 Bcf/d likely won’t be until 2021 and possibly 2022, according to Raymond James.

Per usual, weather remains the ever-present wildcard. Beyond the weather, however, other emerging uncertainties loom, said analysts, including whether Permian and Appalachian production outpaces pipeline takeaway and whether batteries could displace gas peakers.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |