Regulatory | NGI All News Access

Forget the Gorgonzola, Mexican Officials Launch International Offensive to Defend Energy Reform

Senior Mexican officials are battening down the hatches against any signs of political turbulence in the nation’s upcoming presidential election. Above all, they want to preserve the legacy of President Enrique Pena Nieto’s reform program, which spelled the end to the state energy monopolies and the generation of free markets in oil, gas and power.

The official but almost unspoken strategy has been to enshrine the principles of the energy reform within the nation’s leading free trade accords. With an eye on their domestic political calendar, Mexican officials, along with those of the United States and Canada, are pushing for a conclusion to the renewal of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) within days.

At the same time, Pena Nieto and his trade secretary, Ildefonso Guajardo, have been meeting top European officials with whom they have concluded an agreement in principle to renew the European Union’s (EU) trade pact with Mexico.

Mexico’s revived enthusiasm for international trade pacts was confirmed Tuesday when the Mexican Senate voted to sign the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Mexico is the first of 11 countries that are expected sign the CPTPP, the successor to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), from which the United States withdrew when President Trump took office. The new pact overall will account for about 13% of the world economy.

The Mexican election, which includes a major Congressional reshuffle as well as state and local contests up and down the country, takes place on July 1. The inauguration of the new president is due on December 1.

“It’s clear that our officials are trying to ensure that, if the next administration might want to deviate from the energy reform, it would have to rip up these trade pacts,” said foreign affairs columnist Gabriel Moyssen, who works on Mexico’s leading general news daily, El Universal. “And ripping up the trade pacts could spell disaster for the economy.”

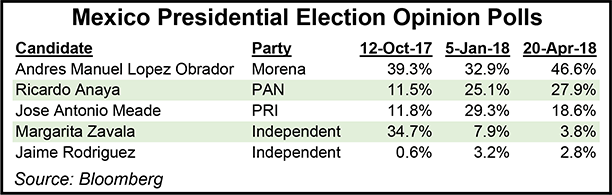

Many supporters of the energy reform fear that the main threat comes from Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, candidate of the leftwing nationalist Morena party. Lopez Obrador has a lead of as much as 20% or more in opinion polls in the presidential election.

Many — though not all — in the business community, and certainly almost all current government officials, view Lopez Obrador as a firebrand who threatens the nation’s hard-won economic stability. But now in his third bid for the presidency, he has considerably mellowed, according to Moyssen.

Other commentators regard Lopez Obrador’s more statesman-like approach to politics, however, is only a veneer.

Whatever the truth, the government appears to be taking no chances. When the renewal of NAFTA was first mooted, many seasoned observers, such as former Foreign Secretary Jorge G. Castaneda, imagined that the negotiations would be prolonged.

Trump’s protectionist views would make agreements difficult, it was reasoned, and it would be only fair to the next Mexican administration to give it a say in what would inevitably be by far its biggest economic relationship.

But these arguments have dwindled sharply as Lopez Obrador’s star has risen and that of Pena Nieto’s hand-picked successor, Jose Antonio Meade, has all but fallen out of the political firmament.

Diplomatic sources say business leaders who wanted to prolong the NAFTA talks were persuaded by the anti-Lopez Obrador lobby, including the nation’s most powerful tycoon, Carlos Slim.

Slim, who has companies involved in a $13 billion project for a new Mexico City airport, made a public statement to reject sharply Lopez Obrador’s criticism of what he regards what may become an immensely costly white elephant.

The principles of the energy reform were enshrined almost from the beginning of the NAFTA negotiations. But they were added later in the talks with Europe. Now the recently announced accord in principle makes clear that for EU investors “this helps ensure access to new liberalized Mexican hydrocarbons and clean energy markets worth up to $15 and $6 billion respectively a year.”

Curiously — or perhaps intentionally (who knows?) — information in bulletins for the media made no mention of the energy section of the pact. Instead, journalists in Europe and Mexico feasted on tidbits of information of new developments on denominations of origin of wines and cheeses.

Little, if any, information was provided on deposits of light crude and natural gas, but plenty about Gorgonzola and Camembert.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |