Regulatory | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

With or Without Kavanaugh, Supreme Court Has Full Plate Ahead, Some Energy Related

Regardless of whether U.S. Circuit Court Judge Brett Kavanaugh is ultimately confirmed to the U.S. Supreme Court, the other eight justices began their term Monday, during which they are going to be tasked with clarifying several legal disputes of interest to the oil and gas industry.

Energy industry-related cases will involve the Endangered Species Act (ESA), administrative agency authority, and the rights of property owners, states and Native American tribes.

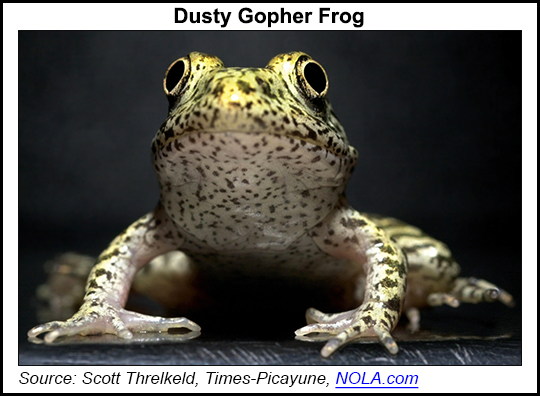

The first case on the high court’s agenda is Weyerhaeuser Co. v. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service [Docket No. 17-71]. At issue are ESA protections that the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) extended to the dusky gopher frog, an endangered amphibian that breeds in ephemeral ponds and was once native to forested wetlands throughout the southern coastal United States, but is now found in a single pond in Mississippi.

FWS declared the frog endangered under the ESA in 2001, and designated its habitat as “critical” in 2012. Weyerhaeuser, a private timberland company, sued after FWS designated land it owns in St. Tammany Parish, LA, as part of the frog’s habitat — despite the animal’s absence. Lower federal courts have ruled against the company, but the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case. Opening arguments were to begin Monday.

Attorney Kent Holsinger, with the Denver-based Holsinger Law LLC, said the Weyerhaeuser case “is indicative of the vast regulatory overreach in recent years. At issue is whether designated critical habitat must be just that. In other words, unoccupied land, or land that is unsuitable for a species, should not be burdened with a federal designation as critical habitat.

“Taken to the extreme, a subdivision could be designated as critical habitat for a species because at one point perhaps they may have been able to inhabit the area. This is not a good use of resources, and is certain to lead to endless litigation with no corresponding conservation benefits.”

Holsinger said state regulatory agencies “are best suited to manage species. Federal designations like critical habitat not only inhibit economic activity but often impede on-the-ground management of wildlife. The regulatory red tape with these designations is stifling.”

The high court also is going to be considering Gundy v. United States [No. 17-6086], with opening arguments scheduled to begin Tuesday. Although the case centers only on the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (SORNA), aka the Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act, which Congress enacted in 2006, it could have implications for all federal agencies.

SORNA requires convicted sex offenders to register with local jurisdictions, but it did not specify whether offenders who committed their crimes before the law was enacted also had to do so. The law, however, authorized the U.S. attorney general to prescribe interim rules for such offenders, many of whom subsequently sued, calling the rules and SORNA itself unconstitutional. When one such case, United States v. Reynolds, reached the Supreme Court in 2012, the high court ruled in favor of the defendant.

But the Reynolds case didn’t answer the question over whether SORNA violated the nondelegation doctrine. In this case, the Supreme Court must decide whether the Justice Department, an agency of the executive branch, violated the separation of powers by enacting rules and thereby encroaching on the legislative branch. The Gundy case could clarify the matter.

If the Supreme Court rules against the government, it could force lawmakers to write more detailed legislation and limit federal agencies, such as the Interior and Energy departments, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and the Environmental Protection Agency, from promulgating their own rules.

Property And Tribal Rights

Opening arguments in a third case, Knick v. Township of Scott, Pennsylvania [No. 17-674], are scheduled to begin Wednesday. The case centers on property rights.

The dispute began in 2012 when Scott Township in Lackawanna County, PA, enacted an ordinance regulating cemeteries. The ordinance compelled property owners to keep any private cemeteries on their land open and accessible to the public during daylight hours. A private landowner sued after being cited for violating the ordinance in 2013, arguing that stones found on her property were misidentified as grave markers.

At issue is a 1985 Supreme Court decision, Williamson County Regional Planning Commission v. Hamilton Bank, which requires a landowner claiming an unconstitutional taking of their property to first seek compensation in state court before filing in federal court. If the landowner prevails, it would make it easier for others to bring lawsuits claiming similar unconstitutional takings to federal court.

The Supreme Court will hear opening arguments on Oct. 30 in Washington State Department of Licensing v. Cougar Den Inc. [No. 16-1498]. In that case, Cougar Den, a corporation of the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, which transports fuel from Oregon to the tribe’s reservation in Washington state, argued that an 1855 treaty with the federal government gives it the right to sell the fuel without an importer’s license and without paying state fuel taxes.

An administrative law judge and the Washington State Supreme Court ruled in favor of Cougar Den, but the state appealed. Six states, including oil and gas producers North Dakota and Wyoming, filed briefs in support of Washington; the others were Idaho, Kansas, Nebraska and South Dakota.

Attorney Thomas Shipps, with the Durango, CO-based firm Maynes, Bradford, Shipps & Sheftel LLP, said the case “really turns upon precise treaty language involving the Yakama Nation. That treaty language is not necessarily shared in all jurisdictions. In fact, treaty language varies from different tribes or groups of tribes, depending on who the negotiators were and what the circumstances were. So in that respect, the case is fairly narrow.

“To the extent that states as a general matter are concerned that this case would provide an exemption to tribal retail companies…I really think is an overly broad concern on the part of those states.”

The Supreme Court is scheduled to hear arguments Nov. 5 in a case involving states’ rights, Virginia Uranium Inc. v. Warren [No. 16-1275]. The dispute involves the Coles Hill deposit, the largest known uranium deposit in the United States, which was discovered in Pittsylvania County, VA, in the early 1980s.

Virginia lawmakers enacted a moratorium on uranium mining in 1982, but the state’s Coal and Energy Commission reported to the governor and the General Assembly in 1985 that the moratorium could be lifted if the state followed specific recommendations to regulate the industry. Court records show no such program has been established to date. The uranium deposit’s owners sued in U.S. District Court for the Western District of Virginia and asked the court to declare the moratorium preempted by the Atomic Energy Act of 1954.

The Supreme Court agreed to take the case after the company appealed its defeat in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit in 2017.

Attorney John Jacus, of the Denver-based firm Davis Graham & Stubbs LLP, said the case is important because it involves the “principles of federalism and when the federal government completely preempts state, and therefore also local regulation. It’s a parallel to what we see in state versus local regulation of oil and gas. It’s a different animal because of the express statutory preemption, but it’s still of interest to the natural gas industry.”

Jacus said if federal law were to preempt state law anywhere on safety-related concerns, it would be in the Virginia Uranium case, “where things could not be more clear.” Court records from the appellate case showed state regulators were concerned with limiting public exposure to radiation, the handling of tailings from the mining process, and the regulation of hazardous waste.

“From that point of departure, you could say there are different types and levels of both express statutory preemption, which is what we’re talking about in this case, and less express, implied and operational preemption,” Jacus said. Under the latter, “states regulate oil and gas activity, and local governments can’t override or conflict with the comprehensive regulation of oil and gas activity by the regulatory body in each state.”

In contrast, Jacus said local governments regulate things such as road impacts, odor and noise. But local regulations will run into trouble, he said, if they impose “a de facto ban on an activity that the state otherwise wants to promote, has promoted in legislation and comprehensively regulates.”

The Supreme Court is currently divided between four liberal justices and four conservatives. In the event of a 4-4 tie, the lower court ruling is upheld and the high court may issue a per curiam decision.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |