E&P | NGI All News Access | Permian Basin

Permian E&Ps Prospering on Technology, But Geological Constraints May Pose Roadblock

The Permian Basin long may reign as North America’s premier oil and natural gas basin, but as a poet said a few hundred years ago, uneasy lies the head that wears a crown.

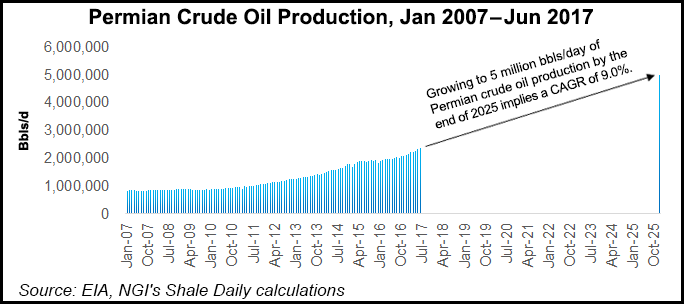

According to a base case in a new modeling scenario by consultant Wood Mackenzie, the Permian’s peak output could increase by 500,000 b/d as new technology adoption accelerates. In the reference case analysis, Permian production is forecast to increase to more than 5 million b/d in 2025.

However, there are risks as exploration and production (E&P) companies adapt to the speedy growth and attempt to pull more oil and natural gas from the massive resource base.

Geological constraints could arise as the play is aggressively developed, which could lead to production shortfalls, and potentially to higher prices early next decade.

“Fully modeling the potential impact of the latest breakthrough technologies reveals measurable upside to Permian peak production,” said consultants. “However, downside risks related to tighter well spacing and well-on-well interference, could bring peak Permian production forward by four years compared to the upside case, putting more than 1.5 million b/d of future production in question.”

Wood Mackenzie’s Robert Clarke, research director for Lower 48 who co-authored a new report about the Permian, said technology gains made in the past few years “have propelled Permian well performance to new levels. However, industry is set up to develop the Permian region’s shale zones at an unparalleled level, testing the geological limits of the play. It is very likely that the upcoming level of activity will introduce a new set of issues, particularly reservoir deliverability.”

Other unconventional plays developed across the U.S. onshore have shown that the “first few years of growth are typically the easiest. Beyond that, producers require more breakthroughs to keep their barrels at the bottom of the cost curve.”

For example, the Marcellus Shale has faced regulatory and midstream bottlenecks, while the Bakken Shale has contended with huge differentials, the Haynesville Shale dealt with a massive cyclical downturn, and the Eagle Ford Shale’s sweet spots were smaller than originally modeled.

“In the Permian, the growth challenge could relate to the industry ultimately finding hard subsurface limits for tight oil recovery,” according to Wood Mackenzie.

Researchers assessed and quantified the “unintended consequences” of high-intensity, long-lateral, close-proximity drilling and fracturing (fracking) on reservoir deliverability. The analysis found that well interference during fracking events could reduce future estimated ultimate recovery (EUR) value by 30% compared with today.

“These reservoir issues could begin to manifest as sweet spots become exhausted,” Clarke said. “Taking into account some bearish assumptions, if future wells tap more difficult rocks, and are not offset by continued technology evolution, the Permian may peak in 2021.”

Wood Mackenzie looked in detail at one of the most prevalent reservoir risks, parent-child wells. Infill wells located next to older producers are routinely called “child” wells, in reference to the older offset “parent” producers. Only a small percentage of wells drilled today in the Permian are child wells but this is expected to change in the coming years.

“When child wells are drilled, they are exposed to different reservoir conditions than the parent,” said Wood Mackenzie’s Alex Beeker, senior research analyst who co-authored the new report with Clarke. “Leaning on history again, we believe future child wells, because they’re effectively drilled into pressure sinks, could have EURs 20-40% smaller than their parent producers. This would massively impact production growth and also limit the amount of cash flow available for reinvestment.”

Matching Technology to Geology

A lot is at stake for Permian operators to ensure they match the technology with the geology. Under the conditions outlined by Wood Mackenzie’s team, the maximum range between the upside technology and downside reservoir risk cases is more than 1.5 million b/d in 2025. That’s more production than the Bakken Shale has ever delivered on an annual basis.

“The ultimate outcome will be some combination of all the factors we modeled,” Beeker said. “Other risk factors will also come into play such as evolving gas to oil ratios and water-injection issues in adjacent zones that will impact pressure regimes and completion designs.

What Wood Mackenzie’s sensitivity analysis made clear is that Permian production is going to grow aggressively for the next few years. Technology also will advance, and EURs for many parent wells will rise. If technologies don’t evolve to meet the geological challenges of the future, there could be downside reservoir risks.

“The technology versus geology tug-of-war has the ability to profoundly alter the future production profile of the region, and ultimately oil price,” Clarke said. “Less Permian supply from 2021 onwards would exacerbate the global supply gap and effectively mean the U.S. cannot deliver what the market believes it can. Other sources of higher cost, conventional production would be needed.”

Still, the Permian is where E&Ps want to be, and it’s proving to also be a lift to credit quality, according to Moody’s Investors Service. Higher recoveries from improved engineering and lower costs have increased return rates and helped compensate from the sharp decline in commodity prices.

While fracking intensity and drilling lengths have increased overall across the most active basin in North America, well costs and drilling times have declined, the credit ratings agency said.

As expected, E&P companies working primarily in the core, today within the Delaware and Midland sub-basins, are better positioned to improve their credit profiles.

Producers spent almost $27 billion in the Permian, which stretches from West Texas into southeastern New Mexico from April 2016 until July. Most of the capital was earmarked for purchases in the West Texas counties of Martin, Glasscock, Howard and Reagan in the Midland sub-basin, and Reeves, Pecos and Ward counties in the Delaware.

“Rig counts also help demonstrate which counties are core to the Permian, with most rigs situated in the westward Delaware and eastward Midland basins. At mid-2017, oil production in those basins had risen to about 2.5 million boe/d, with another 500,000 boe/d of growth expected by 2018.”

The Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas in a note Friday said Permian production rose in August by 62,300 b/d to 2.52 million, with operating rigs numbering 377 at the end of August.

The Players

Operators working in the Permian are among the cream of the crop, according to Moody’s.

ExxonMobil Corp. in January made the largest acquisition in the Permian by price and acreage, a $6.6 billion deal that more than doubled its basin resource and added about 275,000 acres total, mostly in New Mexico. QEP Resources Inc. in the past year paid the highest price per acre, according to Moody’s.

Pioneer Natural Resources Co., Diamondback Energy Inc., Energen Corp., RSP Permian Inc. and Parsley Energy “all have high acreage concentrations in core counties with outsized Permian exposure, leaving them well positioned to prosper,” said Moody’s Assistant Vice President Paresh Chari.

Operators with “mixed” acreage also could see their credit quality improve, if they first focus on developing core acreage, Chari said.

For example, Concho Resources Inc. “holds mixed acreage and has high production concentration in the Permian, while Encana Corp. has a high core percentage and medium concentration to the Permian, and EOG Resources Inc. has mixed acreage and medium Permian exposure.”

Several diversified operators with significant operations in the Permian, including Anadarko Petroleum Corp., Chevron Corp. and Occidental Petroleum Corp., “would likely not see their credit quality improve solely because of their development there.”

Fringe area operators, meanwhile, are left vulnerable to “weak well performance or unexpected declines in production.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |