E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Permian Basin

Permian Best-in-Class at Today’s Oil Price, Says Raymond James

Many U.S. onshore areas may no longer be viable to exploit at today’s oil price, but there are a few select onshore areas, led by the Permian Basin, where it’s still possible to make money, Raymond James & Associates Inc. analysts said Monday.

The Permian’s two major sub-basins, the Delaware and Midland, have multiple horizons of producing wells and potential drilling locations that make the massive land play the premier place to drill, even at today’s prices, said analysts John Freeman, Pavel Molchanov and their researchers.

There are few onshore plays that can achieve a breakeven price today, analysts said in a review of U.S. and overseas areas.

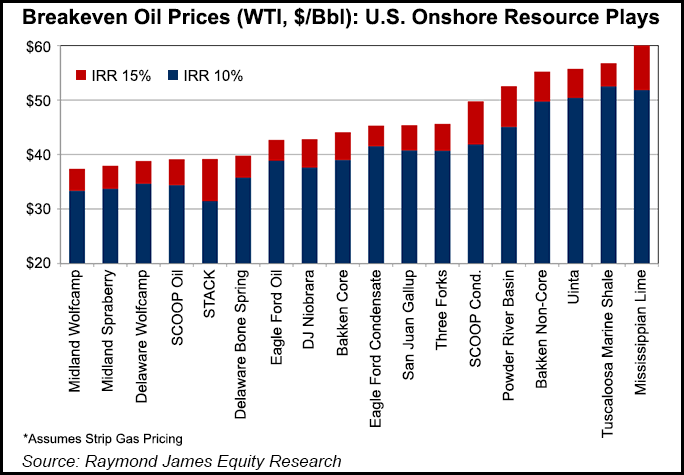

They reviewed 18 U.S. plays and found that 13, or more than 70%, can generate a pre-tax internal rate of return (IRR) of at least 15% at a West Texas Intermediate (WTI) price of $50/bbl. And while there are few in the United States, there are even fewer that work at low oil prices overseas: Only one in 10 of the international areas worked at less than $50 Brent.

In the Permian, the lowest breakeven pricing that works is $37-40/bbl — across both the Delaware and Midland sub-basins. Parts of Oklahoma’s SCOOP (South Central Oklahoma Oil Province) and STACK (Sooner Trend of the Anadarko basin mostly in Canadian and Kingfisher counties) remain economic, along with parts of the Eagle Ford Shale’s oil window, the Denver-Julesburg Basin’s Niobrara formation and the Eagle Ford condensate window, which “are still attractive below $40/bbl.”

At the other end of the spectrum, breakevens are in the $55-60/bbl range for the Bakken Shale’s noncore acreage, the Uinta Basin, the early-stage Tuscaloosa Marine Shale and the Mississippian Lime.

“Given that $30/bbl oil prices do not generate acceptable economics just about anywhere aside from select areas in the Permian Basin, SCOOP/STACK, and (with less clarity) onshore Russia and the Persian Gulf, the oil price environment will eventually have to recover to support a more sustainable level of industrywide investment,” analysts said.

Defining “breakeven” is tricky because producers use a variety of methods to determine where and what to drill. Breakevens can vary among a play, while some operators don’t use full-cycle costs to determine prices. For their review, Raymond James analysts defined “breakeven” as the price for the next well drilled, not full-cycle returns.

Analysts used data from Drillinginfo, corporate presentations, transcripts, press releases and “chats” with management from their coverage universe to focus on U.S. plays that have led overall domestic supply growth from 2010-2015.

“Of the 18 U.S. onshore plays we analyzed, six (or one-third) can provide an incremental well IRR of 15% at or below $40/bbl WTI,” analysts noted. “That number increases to nine (or half) at $45 and 13 (or three-quarters) at $50. That means the U.S. onshore industry’s ”threshold of pain’ increases meaningfully as prices fall from $50 to $35.”

The analysis assumed $3/MMBtu Henry Hub natural gas and used natural gas liquids prices as a percentage of WTI. To adjust for varying corporate tax rates among the companies, analysts calculated breakeven prices using pre-tax values. Generally U.S. E&Ps pay few cash taxes, reflecting (among other things) the favorable tax treatment of intangible drilling costs.

There are, of course, advantages to the low oil price, as oilfield service operators over the past two years have reduced their prices sharply, making some plays still viable. Many of the areas have seen overall costs drop by more than half since 2014, analysts noted.

“Longer term, we still believe the overall U.S. oilfield cost trend (and breakevens) will drift lower as process driven efficiency gains (particularly in the Permian) still have room to run,” said analysts. “Beyond the enviable single-well economics of the Delaware and Midland Basins, what should be clear…is the multi-interval potential of the basin is much greater than virtually every other U.S. ”shale’ play.”

The SCOOP and STACK “deliver adequate returns in a sub-$40/Bbl oil price environment,” analysts said. “In the STACK, which again is not by any means the oiliest of plays, rapidly increasing GORs (gas-oil-ratio) bring forward higher margin oil revenues, thus driving IRRs higher” than in U.S. onshore oil plays with similar estimated ultimate recovery/commodity mixes.

And although it once was the “darling of the shale boom,” the bloom is off the rose for the Eagle Ford because its returns are proving noncompetitive in today’s price environment.

“Additionally, well costs in the Eagle Ford tend to trend slightly higher than that of the Permian Basin, further diminishing returns,” analysts said. The Eagle Ford typically only “has one, at best two landing zones,” unlike the Permian with its multiple intervals and landing zones.

However, while the Eagle Ford today is “inferior” to the Permian, it still remains among the best of the major unconventional plays, analysts noted, “with multiple years of drilling inventory to exploit.”

According to NGI’s North American Shale and Resource Plays 2016 Factbook, even as crude oil prices declined in the last half of 2014 and through 2015, the Permian continued to be one of the only places in the United States where oil production kept rising (see Shale Daily, Nov. 9, 2015). Natural gas production also has risen steadily. Between 2008 and 2014, gas production in the Texas side of the Permian climbed from 3,529 MMcf/d to 4,201 MMcf/d. Between January and September 2015, the region was one of the few areas where gas production still was rising to an average of 4,636 MMcf/d.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |