Regulatory | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Obrador Must Tackle Corruption, Declining Output in Mexico Oil and NatGas Sector

Mexico’s leftist president-elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador and his top energy adviser, RocÃo Nahle, have somewhat quelled investor concerns since the July 1 election by signaling that they will not reverse course on the country’s 2013-14 constitutional energy reform.

However, it remains to be seen whether López Obrador’s anti-corruption platform, which propelled him to a landslide victory, will be robust enough to change the corporate culture at national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) and reverse more than a decade of declining oil production.

Although the reform opened up the formerly state-dominated energy industry to private sector competition, Pemex still exerts an outsized influence over the local hydrocarbons segment.

López Obrador, commonly known by his initials AMLO, has stated his intention to review for irregularities all oil and gas contracts awarded through bid rounds held since the reform. The Comisión Nacional de Hidrocarburos (CNH), which oversees the rounds, has said it will happily comply with AMLO’s request.

However, when it comes to improving transparency, the focus should be on Pemex, not CNH, according to lawyer and academic Miriam Grunstein.

“The government has been so strange because they have been as transparent as the industry can be in the awarding of contracts, meaning CNH,” Grunstein, who serves as chief energy counsel at Brilliant Energy Consulting, told NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index.

Meanwhile, Grunstein said, “a common complaint” from energy companies is, “´how can contractual processes be transparent and Pemex be so opaque?´”

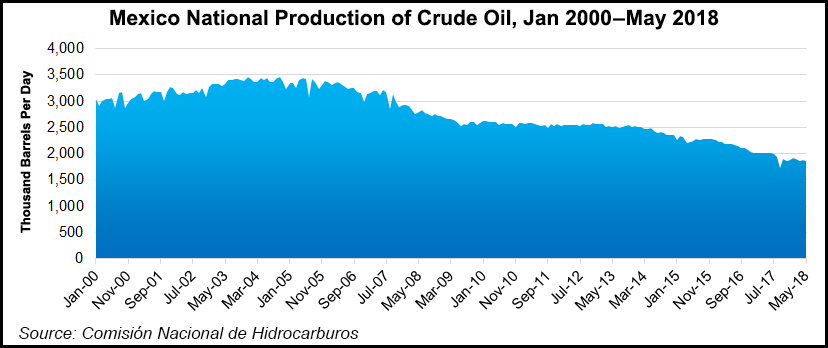

Grunstein, who also works as a professor and researcher at Mexico’s Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, highlighted that Pemex still supplies essentially all of Mexico’s oil production, which has plummeted to 1.9 million b/d from a peak of 3.4 million b/d in 2004.

“Pemex has not fully transitioned to a corporate culture,” Grunstein argued in a paper published last month for the Mexico Center at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. “It is therefore important to note that the reform has not caused the financial, organizational, and technological deterioration of Pemex. On the contrary…we maintain that Pemex is on the decline because the reform was not timely enough, nor was it thorough enough to transform the company.”

AMLO and Nahle have largely staked their energy platform on restoring Pemex to its former glory and reducing dependence on gasoline imports from the United States by adding refining capacity and modernizing the refineries currently in operation. In a radio interview this week, Nahle, a chemical engineer who served in various downstream roles at Pemex prior to her current post as a legislator in the lower congressional house, said works to modernize the existing refining fleet will be carried out over six to seven months after Lopez Obrador takes office Dec. 1, and that either one new refinery or two small refineries will be completed within three years.

Nahle acknowledged that Mexico must also ramp up its oil production to avoid simply substituting gasoline imports for imported crude once the refineries are complete. But experts generally agree that for Mexico to reverse the trend of declining output, the government must take additional steps to improve transparency and efficiency at Pemex.

Many, including Pemex CEO Carlos Treviño and CNH President Commissioner Juan Carlos Zepeda, have called for the government to float a minority stake in Pemex, following the example of Brazil’s national oil company Petróleo Brasileiro SA., i.e.,Petrobras, and Saudi Arabia’s Saudi Aramco. However, an initial public offering by Pemex under AMLO is seen as highly unlikely, as it would be anathema to the statist rhetoric of AMLO and Nahle.

“Through the constitutional change, Pemex could have become a publicly traded company, nourished with private capital and with a more adaptable, less bureaucratic management and structure,” Grunstein argued. “Now it may be too late, due to the scandals surrounding the organization.”

The most high-profile scandal surrounds former Pemex CEO Emilio Lozoya, who was reported by Brazilian newspaper O Globo to have received bribes from embattled Brazilian construction giant Odebrecht in exchange for awarding Odebrecht a US$115 million contract to upgrade Pemex’s Tula refinery.

The New York Times reported in June that Mexico’s ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) government was refusing to press charges against Lozoya out of a fear of damaging PRI’s already dismal reputation ahead of the July election. But with AMLO’s Morena party in control of congress, the new president is expected to make a show of pressing ahead with proceedings against Lozoya, said Verisk Maplecroft’s Karla Schiaffino, Americas politics analyst.

“This is a little bit of a tradition for Mexican presidents,” Schiaffino told NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index the day after the election. “When they come into office they try to use their political capital to make a big stand.

“However, if we don’t see a full implementation of a national anti-corruption system, it will be very hard to have an actual systemic reduction in corruption.”

Schiaffino also said AMLO has been “on the fence” about appointing a specialized anti-corruption prosecutor, and has not floated any possible names for the position.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |