NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Coronavirus | LNG | LNG Insight | Markets | NGI All News Access

More Lower 48 LNG Landing in China, but Pandemic Clouds Trade as Tensions Rise

U.S. liquefied natural gas (LNG) deliveries to China are steadily increasing following a preliminary agreement earlier this year to ease trade tensions, but the deal is now seen in jeopardy given the economic impacts of Covid-19 and the pandemic’s role in souring diplomatic relations between the countries.

In a phase one trade deal signed in January, China committed to a lofty target of buying $200 billion of American goods over the next two years, including $52.4 billion of energy products including LNG, crude oil, refined products and coal. Since April 20, when a U.S. cargo discharged in China for the first time in 13 months, another six vessels have delivered Lower 48 gas to the country, the world’s second largest gas importer, according to ClipperData.

The deliveries come at a time when Asian spot prices are at a premium to U.S. and European gas benchmarks; the Japan Korea Marker has increased by more than 30% since last month. While the rally is on shaky ground given the current economic uncertainty, China has ramped its LNG buying recently as European gas inventories are nearing capacity and global energy consumption has declined.

“It’s generally a good thing given that demand has collapsed,” said Rice University’s Anna Mikulska, a nonresident fellow in energy studies at the Baker Institute, who spoke about the Chinese market slowly reopening to American LNG exports.

However, there was never any significant impact on U.S. output when China imposed steep tariffs on American imports, as cargoes that were purchased by Chinese buyers were rerouted to places such as Japan or South Korea in exchange for Australian or Qatari cargoes. The phase one trade deal left all tariffs in place, but in March China began accepting applications from buyers for waivers of the 25% tariff on LNG imports, paving the way for the recent American arrivals.

“The real payday for U.S. projects would be if tariffs are lifted and then the Chinese might sign some long-term contracts and that might backstop some project development,” said Poten & Partners’ Jason Feer, global head of business intelligence. “It’s just sort of a two-year truce right now, and that’s not long enough to be willing to sign long-term contracts under the assumption that we’ll fix all of this.”

There is the possibility that tariffs could be lifted in a second phase agreement, but relations have deteriorated since January.

President Trump has threatened to end the agreement if Beijing doesn’t begin adhering to the terms. Tensions also have increased as the United States and other countries have raised questions about how China handled the Covid-19 outbreak, threatening to reignite the trade war only a few months after the detente. China has defended its response and pointed to mismanagement outside its borders.

“Questions around the viability of the agreement appear bleak as ever,” data intelligence firm Kpler said in a note last week. “…In the months ahead, the storyline will center less on deal compliance and more on a willingness of U.S. and Chinese companies to transact with one another at all.”

While China’s recovery has so far been uneven, domestic gas demand has remained resilient. ClipperData said Tuesday 23 LNG tankers discharged in the country over the prior seven days, from 21 at the same time last year.

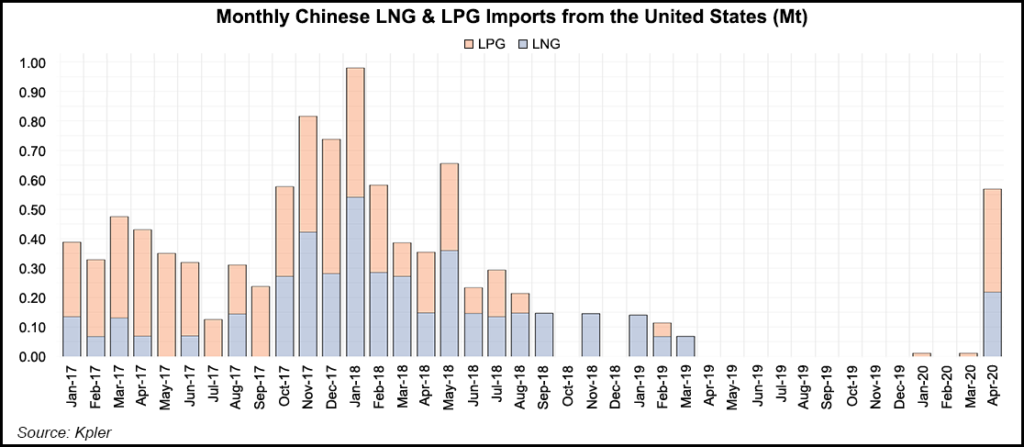

Arrivals of U.S. LNG in the country last month alone finished in positive territory for the first time since last year at 0.22 million tons (Mt), Kpler said. Liquefied petroleum gas from the United States also hit a two-year high in April. Crude purchases are the outlier for now, Kpler noted, as Chinese refiners appear more willing to take oil from the Middle East.

The question of whether U.S. gas imports hold up is murkier than it was earlier in the year, when the unprecedented targets set in the phase one deal were greeted with skepticism.

“The targets were never realistic,” said senior adviser Scott Kennedy of the Center for Strategic and International Studies in a recent analysis he wrote. “They were gaudy numbers meant to impress.” Kennedy noted that U.S. exports to China during 1Q2020 were down 10% from the same time last year, while the phase one deal had forecast an increase of 36.6% in 2020.

“When the phase one deal came out, nobody could figure out how you’d actually make that work,” Feer told NGI. “Their promises to buy vast quantities of U.S. produced energy and other commodities” were difficult to believe.

Feer said the deal was predicated on dollar amounts and not volumes. Since the agreement was signed, oil and natural gas prices have plunged, meaning China would have to import even more fuel to meet the values set forth in the initial agreement.

The trade groups LNG Allies and the American Exploration and Production Council on Wednesday sent a letter to Trump urging the administration to find a way forward with the Chinese government to secure more long-term supply agreements. U.S. exporters face stiff competition from other suppliers such as Qatar and Australia, while new liquefaction projects face the daunting task of clinching commercial arrangements in a market flooded with cheap spot volumes.

“In addition to stepping up short-term gas and oil purchases, we encourage you to allow China to meet a portion of its phase one commitments by entering into new long-term sales and purchase agreements with U.S. LNG export companies that are building new or expanding existing LNG export facilities,” the groups wrote.

The letter echoed other calls in recent weeks to reshape the agreement given the economic and energy market conditions that have been caused by the pandemic.

“Even if China were to buy huge amounts of LNG cargoes within the next year or two, it won’t necessarily help U.S. LNG development and would mostly be bought on spot,” Mikulska told NGI. She said there’s a better chance China could hit the kinds of targets laid out in the two-year deal if it instead commits to buy LNG in the future.

Trump at a White House press briefing this week said he wasn’t interested in revisiting the terms of the phase one deal.

“This is the best option right now, and they have a good excuse for doing so,” Mikulska said. “Covid-19 is the best excuse you can have for giving up some of these positions that require China to buy vast amounts of energy or other products” in the near-term.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |