Shale Daily | E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Lower 48 Fracking Operations Reportedly to Hit Low Point in April, with Permian Taking Biggest Hit

The historic slump in oil drilling is likely to result in the largest monthly decline in completions activity ever recorded in the United States, according to an analysis by Rystad Energy.

Brought about by the coronavirus pandemic and low oil prices, the total number of operations where hydraulic fracturing (fracking) has already begun “will end up below 300 wells in April,” the firm said Wednesday.

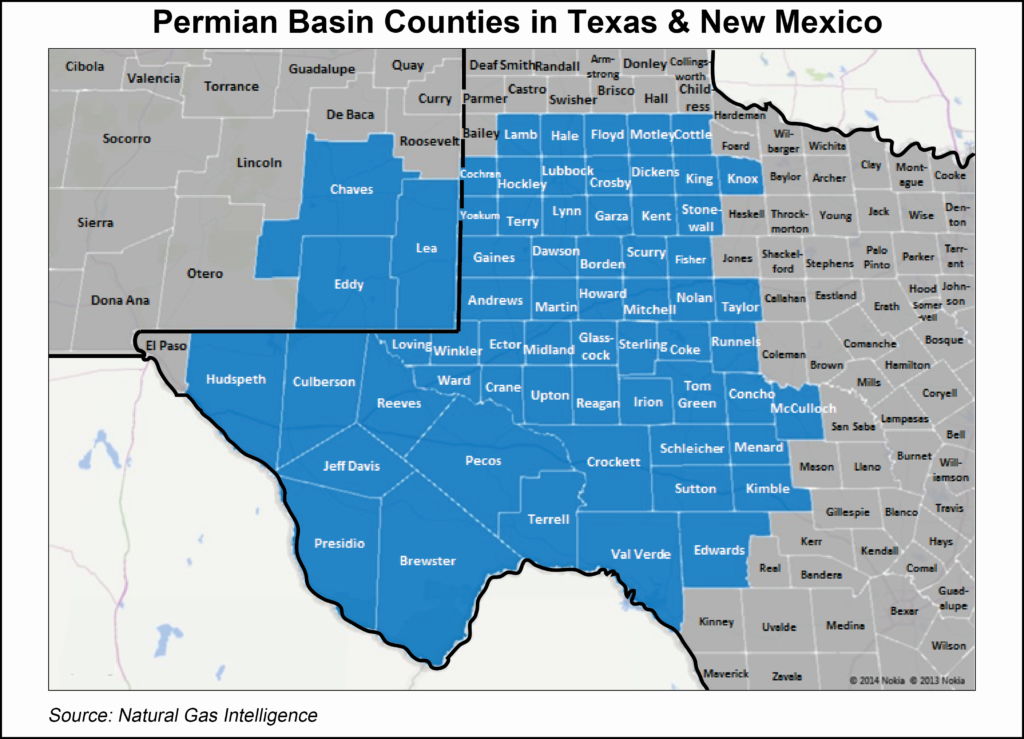

Analysts estimates close to 200 wells would be affected by the decline in the Permian Basin, along with less than 50 wells each in the Bakken and Eagle Ford shales.

The estimate, if accurate, would translate into a 60% decline in fracking operations from the peak seen in January to February. Many public and private exploration and production operators have begun implementing frack holidays, as they cut crews and rigs.

In March, Rystad reported an extreme 30% monthly decline in the number of frack jobs already begun in the three major oil basins, which was a decline from 807 in February to only 550. Also, nationwide fracking activity, on a completed jobs basis, may have declined by around 20% in March, according to the firm’s estimates.

“With such a rapid decline in fracking already visible, very little activity will be happening in the oil basins during the remainder of the second quarter of 2020,” said Rystad’s Artem Abramov, head of Shale Research.

“The natural base production decline, which we have seen as an absolute floor for production, therefore becomes an increasingly relevant production scenario.”

Assuming there are no new horizontal wells put online beginning in April, Rystad estimated total light oil (LTO) production would decline by 1 million b/d in May, 2 million b/d by July and by 3 million b/d from October to November. The Permian is seen accounting for more than half of nationwide base decline.

U.S. LTO operators, which have begun voluntary production curtailments, are expected to try and deliver on the reductions “as much as possible from the natural production decline, as opposed to shut-ins of producing wells,” but some of the marginal, least economic volumes are being shut-in too,” analysts said.

“The magnitude of the base decline for U.S. LTO sounds extreme in the context of what we see for other supply sources globally,” according to Rystad. “But ironically, the steep decline is actually too late to save prices; despite the oversupply issue, standard operation patterns prevent operators from simply turning the faucet off.

“These days, Permian wells require about two months from the moment frack operations start until they produce first oil, and require about three months before they reach peak output.”

That means the decline in started jobs which began in March should result in fewer wells turned to sales in May, which could lead to a drop in peak production in June — if normal operational patterns are maintained.

“On the demand and storage side, the market is already moving through its toughest challenge yet,” Abramov.

The West Texas Intermediate front month sell-off on Monday “emphasized how broken the physical market might be already,” he said. “We are therefore concerned that significant production shut-ins will be required in the next few weeks to bring the market into the balance in a brutal manner.”

In addition to Rystad’s standard analysis of frack activity, which is based on incomplete reporting in recent months and the empirical reporting delay adjustment factors, the firm has begun using satellite data to systematically monitor more than 40,000 permitted and drilled locations across the United States.

Rystad’s methodology is based on monitoring the equipment intensity on each pad or permitted location. The data then is analyzed over time to identify the main pre-production activities in each well life cycle, from pre-spud to main drilling and fracking.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |