Regulatory | NGI All News Access

In AMLO’s Mexico, Pemex Undergoing Yet Another Facelift

Barely eight months into the new government of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, Mexico’s national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) is facing an identity crisis, according to Mexican energy experts.

Is Pemex a competitive energy company, as was the mission of the energy reform of 2013, or should it now be regarded as a government department, like Public Health, Education and the armed forces? The response has led to a verbal wrestling match among rival bands of politicians, analysts and the nation’s “twitterati.”

What most recently sparked the dispute was a column by Pablo Zárate in the business daily El Economista. Zárate, who heads the Pulso Energético think-tank, argued that Pemex has given Mexico over the years billions of dollars and hundreds of thousands of jobs. However, now that the enormous abundance of the Cantarell complex in Campeche has all but vanished, the government’s social spending is no longer being supported by Pemex.

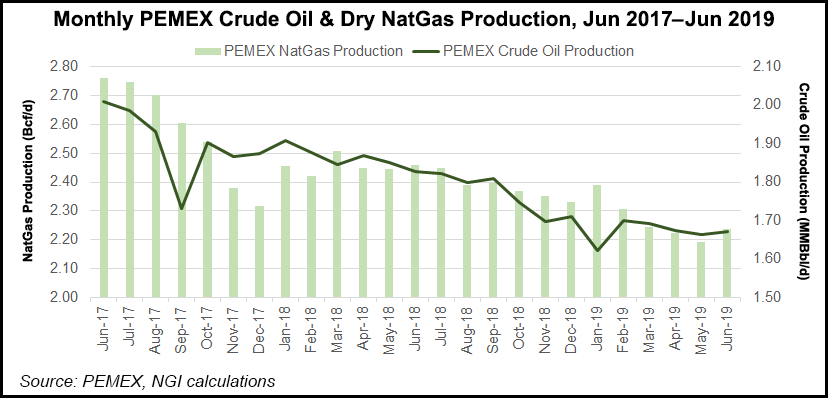

In fact, the very opposite appears to have occurred. Pemex, burdened by a $106 billion debt and declining oil and gas production, needs government support in order to fund its investment plans. Other state-owned companies, such as Colombia’s Ecopetrol and Brazil’s Petrobras, can raise capital in their local stock markets, but not Pemex.

And so the administration of López Obrador has decided to lavish Pemex with government funds and tax cuts in order to “sow oil,” the idea being that the government will be repaid by booming production in the final three years of the current government. To such an extent, Zárate wrote, “One way or another, Pemex now owns Mexico rather than the other way round.”

Miriam Grunstein, non-resident scholar at Rice University’s Baker Institute, told Mexico’s Televisa network that the government’s largesse with Pemex far exceeds the dimensions of the potential resource base on which it is being pledged. “These stratospheric reserves are a product of fertile imagination,” she said.

The government’s aim is that Pemex can reap its own riches without farmouts. “But Mexico is huge in energy terms and Pemex simply can’t go it alone,” Grunstein said. And, she added, the recently published Pemex business plan “includes very little about business,” and is “more like a plan for social spending with a large dose of ideology.”

Grunstein’s description of Pemex not as a company but an agency of the Mexican state, ironically matches the definition ruled by a U.S. court in the case of the 1979 Ixtoc blow-out in the Bay of Campeche. The blowout resulted in an oil spill still regarded by many as the world’s biggest ever, causing havoc to tourism and the environment on both the Mexican and U.S. coasts along the Gulf of Mexico.

Pemex was clearly to blame but, under the terms of the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, could not be held responsible because it was not a Mexican company but rather a Mexican government agency.

That judgement came as a huge relief to the Mexican government, and soon the state monopoly’s fortunes improved, reaching a crude production peak of 3.4 million b/d in 2004, more than twice its current production.

By then, with incentive-based service contracts — now being reintroduced according to the Pemex business plan — the monopoly had another name, the paraestatal. In Spanish that means a body that works in conjunction with the state but does not form part of the public administration, although Pemex most certainly was, with the nation’s president in effect the chairman of the board.

The 2013 energy reform, which opened the oil industry in Mexico to the private sector since its nationalization in 1939, led to another name. In all official documents, Pemex was described as a “productive state enterprise,” a moniker that caused many a quip in view of Pemex’s notorious inability to turn a profit.

From 2013 onwards, after decades of being a law unto itself, Pemex was subjected to regulation by the upstream Comisión Nacional de Hidrocarburos (CNH) and the downstream Comisión Reguladora de EnergÃa (CRE). But both regulators have been considerably weakened under the current Mexican administration as Pemex undergoes yet another facelift.

While state oil companies in the wake of the reform swarmed across Mexico in search of opportunities in the upstream auctions launched by the CNH, Pemex has never operated outside of Mexico, even when it ranked as the fourth largest oil company in the world. Not even has it cast an eye on the very small industry of neighboring Guatemala’s El Peten province, within eyesight of the onshore Chiapas and Tabasco oilfields in southeastern Mexico, nor has it ventured slightly north into U.S. shale fields, as Ecopetrol did recently.

Upstream auctions have now been cancelled, and Pemex once again is being depended on to rescue the nation’s energy sector. It remains to be seen what Pemex will look like at the end of the six years of this current administration, but if it is unable to stem the decline in hydrocarbons production and reserves, the government’s current bet of trying to ”make Pemex great again’ will come under sharp criticism, and another identity will be called for.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |