NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Coronavirus | LNG | LNG Insight | Markets | NGI All News Access

Global LNG Production Shut-Ins Seen Imminent as Prices Continue Falling

The outlook for liquefied natural gas (LNG) is growing dimmer as prices across the world have fallen by double-digits this year and the Covid-19 pandemic continues to ravage demand in markets already awash in supplies, suggesting production shut-ins are practically guaranteed in multiple countries.

But the persistence of global trade flows and the additional elements of uncertainty that have arrived with the pandemic make it difficult to gauge precisely which producers will shut-in and to what extent they’ll curtail volumes.

U.S. cargoes have already been canceled and more are likely ahead as the price spread with key markets in Asia and Europe continues to narrow. Flexible contracts and a higher cost of supply in the United States leave its producers more vulnerable to shut-ins. Yet global gas prices have been falling since last year with no significant decrease in domestic LNG output.

“It’s hard to say if or when there will be significant LNG underutilizations as these are unprecedented times and there’s not any similar time in U.S. LNG history to reference for guidance,” said Schneider Electric analyst Christin Redmond.

Feed gas deliveries to U.S. facilities have slipped from highs earlier in the year. Most recently, Train 1 at Sabine Pass in Louisiana was offline for about 10 days, but there’s no way to say definitively whether that was an economic shut-in or planned maintenance, said Genscape Inc.’s Allison Hurley, team lead of LNG and Proprietary Natural Gas.

Others think the signs are clearer. “There has been a supply response, we’ve seen LNG production from the U.S. decreasing, particularly from Sabine Pass,” said Rystad Energy’s Carlos Torres-Diaz, head of gas and power markets. “Since demand is dropping in Europe and internationally in tandem, there will likely need to be further downward adjustments” from suppliers across the world.

The oil price war between Russia and Saudi Arabia has also sent crude prices tumbling by double digits, with Brent crude trading at or just above $30.00/bbl through the remainder of the year. The rout has had an even harsher effect on U.S. and Canadian crude prices.

IHS Markit said this month that the impact of low oil prices could result in a drop of up to 10 Bcf/d in North American associated gas volumes by the end of 2021 as oil-directed drilling slows. The massive supply in reduction could also help “offset or even overtake the drop of gas export demand as a result of Covid-19,” the firm said.

“One of the big complications about this big oil price drop…is if oil production in the U.S. begins to decline, that means that the volume of associated gas will also decline, and that should raise the U.S. gas price,” Western LNG CEO Davis Thames told NGI.

If Henry Hub prices increased that would further pressure the LNG exports tied to them and make it costlier to lift cargoes in the United States if prices overseas remained low, which isn’t a guarantee.

“There’s an interplay between all those prices,” said Poten & Partners’ Jason Feer, global head of business intelligence, referring to Henry Hub, the Japan Korea Marker (JKM) and the Dutch Title Transfer Facility (TTF).

“There’s been all these inversions, JKM dips below TTF, TTF dips below JKM,” he told NGI. “And that’s what you’re starting to see, this very volatile market, very unpredictable, very responsive to news, a lot of uncertainty. That’s the problem, nobody quite knows what to expect.”

Export margins are barely negative through the summer, with TTF and JKM forwards trading below $3.00/MMBtu. They would likely have to go far deeper to prompt the sort of shut-ins that would better balance the global market, said Thames, who formerly served as Cheniere Energy Inc.’s CFO.

In a note earlier this month, Goldman Sachs said the decision to cancel a U.S. cargo hinges on variable costs like fuel for ships or regasification fees at import terminals overseas. Take-or-pay fees at U.S. terminals and even most shipping expenses are sunk costs. But variable export costs are not publicly available, leading to estimates on the magnitude of shut-ins that vary widely.

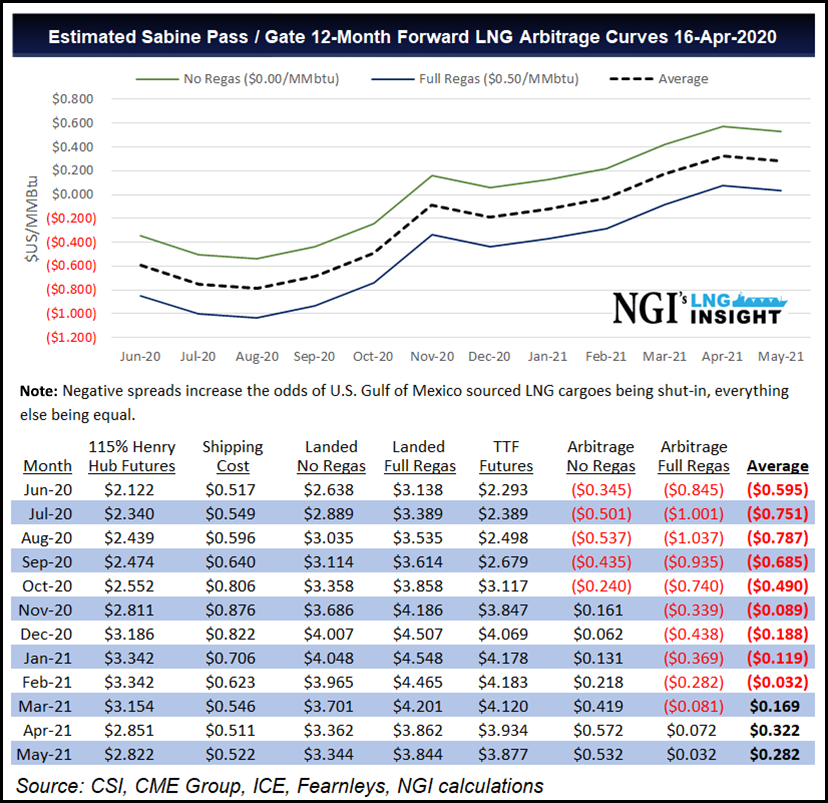

Goldman is still forecasting up to 1 Bcf/d of U.S. shut-ins this year. Poten & Partners recently said that it expects roughly 10 U.S. cargoes to be cancelled this summer. Assuming offtakers are paying 115% of Henry Hub prices and including variable costs such as those for shipping and regasification, even NGI calculations show U.S. LNG out of the money through the remainder of the year.

But in suggesting that shut-ins might not be all that severe, Thames noted that “a lot of people already have regas contracts, they’ve already paid that, and so it’s a sunk cost and it doesn’t matter on the margin.” Moreover, offtakers are likely to move cargoes from the United States even at a profit of just a few cents per MMBtu.

In other instances, Feer added that “people sign long-term contracts because they need the volumes, and so they’re just going to eat the price.”

As the pandemic has stretched on, however, prices continue to hit new lows. The JKM spot price hit a record low on Friday of $2.186, while reports surfaced that traders have made record-low deals for cargoes that will be delivered to both Asia and Europe at or below roughly $2.00/MMBtu in the weeks and months ahead.

Oil’s slide has also left LNG producers in other countries with more crude exposure vulnerable. Oil-indexed contracts accounted for about a quarter of gas purchases in Europe in 2018, according to the International Gas Union. While most of those were predominantly pipeline imports, oil is still linked to LNG purchasing in Europe, while the pricing formula is far more dominant in Asia, where oil-linked contracts accounted for about 67% of purchases in 2018.

With Brent at around $30/bbl or slightly above through the remainder of the year, and assuming 11-15% slopes, that could test the breakevens of some LNG producers with oil exposure and prompt shut-ins in other countries, especially if oil falls further. While steep oil production cuts have been announced by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, the United States, Canada and others, they’re likely not enough to immediately balance a market swimming in crude, analysts have warned.

Australia’s primary export market is in Asia. Billions of dollars in investment decisions on train expansions and fields to feed LNG production have already been delayed in the country since the oil price crash, from Woodside’s Burrup Hub Expansion and its Scarborough Gas Field to Santos’ decision to delay its Barossa gas field project, which was to replace gas supplies for Darwin LNG.

Exports have also been halted from Egypt’s only operational LNG plant at Idku near Alexandria due to the impact of low prices and the pandemic. The restart of the Damietta plant in the country has also been pushed back. Other projects in Africa, such as ExxonMobil’s Rovuma LNG have also been sidelined due to market dynamics.

While there’s still expected to be LNG demand growth and a surplus this year, Poten & Partners recently said that LNG export projects representing 227.5 million metric tons/year of supply could ultimately face delay due to the coronavirus.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |