Duvernay Production, Costs Varying Widely

Four years after inspiring a Canadian mineral rights leasing rush, a Louisiana-sized Alberta drilling target — known as the Duvernay among geologists and dubbed “new millennium gold” by stock promoters — is turning out to be a mixed bag.

Well costs and production vary widely, according to rare disclosures of early exploration results Wednesday at a Calgary conference of the Canadian Society for Unconventional Resources and Society of Petroleum Engineers.

Rather than a sure bet, “it’s still an emerging play from our perspective,” said Shell Canada geoscience team leader Holger Mandler. “Profitability will still have to be proven. There’s still lots of uncertainty.”

The formation carpets a 140,00-square-kilometer (56,000-square-mile) region of northern and west-central Alberta with a gas- and liquid byproducts-bearing layer, 2,500-4,000 meters (8,250-13,200 feet) deep and 20-70 meters (66-231 feet) thick.

Geologists named the structure after a town near the site where it was discovered in 1950. It was left alone by pioneer drilling because the rock was too dense for the technology of the era to loosen.

The formation got its glowing stock exchange nickname because its liquids are dominated by condensate, also known as natural gasoline. The material fetches high premiums over the benchmark oil grade (WTI in the United States, Edmonton Par in Canada) because it is in high demand as diluent, or thinner, used to make Alberta oilsands bitumen flow in pipelines.

The resource appraisal arm of the Alberta Energy Regulator estimates that the Duvernay contains 62 billion bbl of liquids and 443 Tcf of gas. But the large-scale earth science maps do not have Xs marking sweet spots rich enough for commercial use.

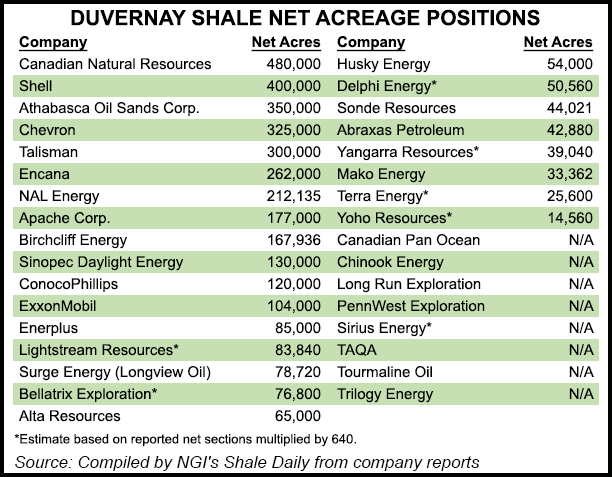

Industry spent C$2 billion (US$1.8 billion) to scoop up large spreads of Duvernay gas and oil rights in 2010 at provincial lease auctions and a record C$3.6 billion (US$3.2 billion) more in 2011 as advancing technology fueled visions of tapping into the vast, untouched natural wealth.

Well productivity and costs vary widely to date in early runs at adapting horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (fracking) to Canadian conditions, said Mandler.

Liquids output ranges from 50 to more than 400 bbl condensed per million cubic feet of well flows, he said. Costs per well cover a wide waterfront from C$4 million to $10 million (US$3.6-9 million).

The most comparable U.S. shale deposit, the Eagle Ford, achieves 50% higher peak liquids output. The Duvernay is a tighter structure of silica and carbonates, which shatters well when fracked but still resists free flows.

Industry is discovering that geological structure changes as the new generation of horizontal fracking wells spreads northwards, said Jill Haynie, a senior Enerplus Energy geoscientist who works in Denver on the North Dakota Bakken and spin-off drilling plays.

In the United States, shale targets occur as layer cake-like stacks of rock zones. As drilling goes north into Canada the targets turn into thick wads where the best gas and oil-bearing sections can be difficult to identify.

The Duvernay also poses multiple land-surface challenges to industry, Mandler said.

The Alberta region has numerous aboriginal communities. Unlike their American counterparts, Canadian natives have special status as First Nations in the national constitution, must be consulted and accommodated by industrial or government projects and are making ever-higher demands before regulatory agencies and in the law courts.

The Duvernay drilling target area is also studded with well-established farming, ranching, and country residential and recreational districts, Mandler pointed out. Starting this winter, the AER will use the region for trial runs of a new “play-based” regulatory regime requiring increased disclosures of development plans by industry and acceptance of projects by communities, as opposed to traditional approvals of wells and production facilities one at a time.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |