Infrastructure | E&P | Marcellus | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Utica Shale

Cracking Appalachia’s Ethane Code Part 2: Shell’s Cracker Is ‘Tip Of The Iceberg’

The Appalachian Basin’s shale formations helped to birth the natural gas renaissance in North America, and the region now is poised to join the Gulf Coast as a major petrochemical hub, a group of experts said Monday.

(See Part One, Part Three)

A webinar hosted by NGI’s Shale Daily, “Cracking the Ethane Code in Appalachia,” delved into all sides of the petrochemical equation. Last spring a unit of Royal Dutch Shell plc made a final investment decision (FID) to build a multi-billion dollar cracker about 30 miles northwest of Pittsburgh, officially signaling that the region will be a major hub. Sited on 400 acres in Beaver County, adjacent to the Ohio River in Potter and Center townships, the project as designed would have capacity to produce 1.6 million metric tons/year (mmty) of polyethylene and 1.5 mmty of ethylene. Construction would require 6,000 people at its peak, while another 600 permanent employees would staff the facility when it becomes operational in the early 2020s.

Shell’s project will not only be huge, but transformational in all ways, said an all-star panel of experts during the one-hour webinar. Joining NGI Associate Editor Jamison Cocklin, who was the moderator, were Consol Energy Inc.’s Don Rush, vice president of marketing, and James Cooper, senior petrochemical adviser to the American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers trade group. Also joining in the conversation were Denise Brinley, special assistant to the secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development (DCED), and Danielle Sandusky, president of Denver-based Level 2 Energy, a risk management firm.

“Like anything, the more demand and takeaway capacity that exist for ethane, the more that is likely to be processed and sold in basin,” Rush said.

Pricing can be good on the supply side regardless, Rush said, but Consol attempts to take advantage “with some creative, fairly unique contracts that have allowed us to significantly catch some premiums. The Shell deal is another layer in the overall portfolio we have advantaged for our ethane, and there is incremental value in doing so.”

As more liquids are transported out of Appalachia, Consol has remained flexible, giving it different options and different price exposure.

“Anytime we have a chance to bring new demand to the region, we take a real hard look at how we can do that,” Rush said. Consol is “always looking for partners and different arrangements,” and the Shell project will “further everyone else’s understanding of the long-term benefit to the region and the United States of proper development of the Utica and Marcellus shales…It does give us further confidence that more things come after this.”

For example, Consol expects the cracker to result in more “downstream opportunities” that set up shop close to the facility. “We’re confident that those industries and many other demand centers will look to the cracker as a low-cost energy source. We can see it happening in a lot of other industries,” including the fertilizer and ammonia sectors. “A lot of these U.S.-based plants have a global competitive advantage now…It should lead to more business here, and we hope it can be a major positive for the region. We hope this is just the tip of the iceberg to come.”

The way Consol has set up its portfolio, “and likewise, the way that Shell is connected to multiple, different de-ethanization facilities and supplies they are putting, we are able to supply the Shell plant from West Virginia, Pennsylvania and Ohio,” Rush said. “When the plant is in service, there will be a lot of different components that will go into position at that time…”

Depending on the economics at the time will determine which Consol assets are used for the Shell contract versus other contracts in the portfolio, Rush said.

Backyard Feedstock Bonus

A “quirk” in the petrochemical boom followed the shale revolution out of Appalachia, Sandusky said. Once gas production was in full swing, cracker capacity expansions followed by greenfield facilities, were put on the drawing board. However, even though Appalachia became the nation’s No. 1 gas producer, nearly every single cracker expansion was for the Gulf Coast.

“Basically, what was set up were nationwide tiers of ethane recovery economics,” Sandusky said. “Historically the best netbacks were going to the Gulf Coast plants. All of the processors down there extracting and recovering ethylene from the stream have the best economics because of the proximity to all the offtake facilities…

“The further you got away from that area, the transport costs and the lack of mobile market networks, the worse recovery economics…In the earlier years of the shale boom, Appalachian producers pretty much had one good option and that was the gas stream.”

The addition in 2013 of the Mariner West 1 project to offtake ethane to Sarnia and Marcus Hook, as well as the Appalachia-to-Texas Express (Atex) pipeline to carry liquids to the Gulf Coast “didn’t really change the calculus that much just because they also brought on new supply with producers that signed up for long-term commitments,” Sandusky said. “So you still ended up with an oversupply of the market, with the Gulf Coast being the most advantaged and with these tiers of netbacks the further you got away from the Gulf Coast.”

Producers continue to ship on Mariner, Atex and various pipes because of the long-term commitments, “but in general, you are still talking about a solid 10-15 cent gap per gallon worse in the recovery economics for your Appalachian producer than somebody on the Gulf Coast,” she said.

Now Appalachia ethane is by some estimates at around 300,000 b/d at the peak, “and it’s projected to still grow,” Sandusky said. “The majority of that production is still going into the gas stream, but once you max that out and start shipping, you run into those transportation costs…that are a big disadvantage over somebody say, in the Eagle Ford Shale or somewhere on the Gulf.

“Depending on whether you are going to Sarnia or Marcus Hook or the Gulf, you are paying until the new cracker comes on, anywhere from 14-20 cents per gallon to ship a commodity that’s worth 25 cents before you pay for the recovery itself and any storage fees. That can still leave you with a net negative, so at that point, once you’ve maxed out the gas stream and are looking at paying those transportation fees, having a local cracker, somebody in your backyard that’s willing to pay you a market price for your ethane without having to pay for those fees, is going to be huge.”

Shell’s facility should have an impact on Appalachian ethane prices, depending on when the facility comes online and relative to the ethane supply growth in the region, Sandusky said.

“There are some robust growth projections out there that suggest quite a bit of new supply. So by the time the cracker comes on, we could be in a situation in the early 2020s where we’re sitting back at a point that where we have ethane for pennies on the dollar per gallon because we’re sitting at a point where we’ve maxed out the gas stream and potentially at that point maxed out the takeaway pipeline capacity. So, the local prices could be really depressed.

“If at that point you added 100,000 b/d to local demand, which could be a quarter or more of the local supply, that would probably have a pretty dramatic impact on prices.”

However, drilling investments overall have been more conservative, with the dry Utica attracting dollars that otherwise may have gone to wet gas drilling, Sandusky said. “That’s the balance you are looking at and it could have a really dramatic impact.”

Big Picture Economics

Looking at the bigger picture, the national demand for ethane is dramatic, Sandusky said. “We’ve got somewhere around 1.2-1.3 million b/d of ethane demand in the country. The economics overall have been pretty stellar, which has justified a lot of the investments in more crackers, expanding and upgrading capacity…with a vast majority of those in the Gulf…”

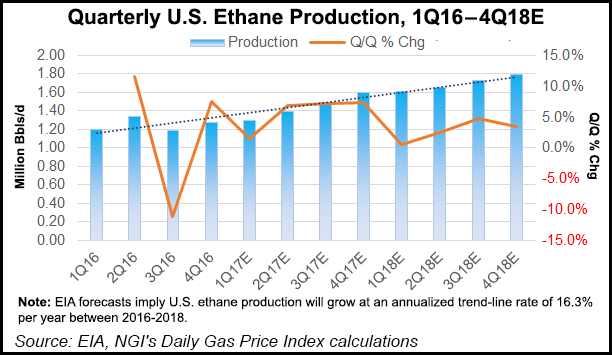

The Energy Information Administration in January estimated that ethane production could rise to 1.7 million b/d in 2018 from 1.25 million b/d in 2016. Expansions at existing ethylene plants contributed to a 170,000 b/d increase in ethane consumption between 2013 and 2016, the agency said.

By mid-2018, construction is expected to be completed on six ethane crackers and one is to restart on the Gulf Coast, which together collectively would be capable of using 450,000 b/d of feedstock. Ethane consumption is forecast to increase by 310,000 b/d between 1Q2013 and 4Q2018 as the plants ramp-up operations.

Depending on what projection is used for production, it could mean “pretty much the entire U.S. ethane market leaving none to go in the gas stream,” Sandusky said. “You are looking at potentially being short overall. That in general is how the free market tends to swing…That does mean that Appalachian prices could get a bump in the near-term, especially if you are looking at those price lines taking recovery products away with producers looking at that as a sunk cost.

“Those volumes are going to flow without regard to transport costs to get there. You’ve got 10 years’ worth of commitment for at least Atex going south to the Gulf…To draw additional barrels that would have otherwise been in the gas stream, the prices will need to get to the level where the producers will have to recover and put ethane on those pipelines to get to market.”

The price needs to be equivalent to the gas price plus the cost to recovering it, Sandusky said. “You could grow Appalachian production past all the capacity of the pipelines…then you could start to see pressure back on local prices…But the other issue is that if the cracker economics start to fall apart, and you’ve got 2 million b/d of ethane being processed, the Appalachian market is going to be vastly oversupplied…You could see the pushback and the lid put back on prices.”

One Word: Plastics

How will Shell’s cracker stack up against the burgeoning opportunity still at play along the Gulf Coast and in Canada?

“Basically we think that most of that demand will come from the surrounding area,” Cooper said. Pennsylvania alone has more than 50 different plastics processing facilities, while Ohio has 75 to 80. There’s also plenty of business in nearby New Jersey, Illinois and Michigan. “You’ve got all these different facilities right in that local area, within a short distance where it is feasible to ship…especially resins, since we are talking about nonhazardous materials, then you are talking short-haul over the roads…If you can move some things by barge, some things by rail, that’s icing on the cake…

“The big gamechanger is having it so close,” he said of the Shell facility. Having co-located products “makes Shell very competitive. It’s why it was willing to entertain a multi-billion dollar investment.”

The plastics industry continues to be a job creator across the Midwest and Great Lakes region into the Northeast market, Cooper said.

“Finished goods manufacturing has been taking place in that area for decades and decades, back when steel and iron ruled. You had all this raw material coming from the Great Lakes, and it made sense for finished goods to start up there. Some finished goods obviously did leave the country, unfortunately, but many stayed and retained their business here in the United States.

“So what happened was, there was this dislocation between the raw materials because of the production started coming out of the Gulf Coast…You still have all those finished goods up there that are robust businesses and they are having to ship their raw materials from long distances. Now it’s all going to be co-located again.”

Shell’s cracker would only have so much capacity, Cooper said. “And there’s so much demand out there. Shell’s going to do just fine. And the Gulf Coast producers are going to continue to do just fine as well. They are going to continue shipping resin up because Shell is not going to be able to fulfill all of the capacity by itself.

“What’s great is the United States is in a position right now, especially for ethylene, where we’re very advantageous producer from an energy standpoint because we are energy intensive as an industry and also from the resin standpoint…”

Before the shale explosion, about 50% of U.S. ethylene was supplied using naphtha sourced from overseas facilities. “Over the course of the last few years, because of shale development, now 80% of ethylene comes from ethane,” Cooper said. “That’s why we’ve got this tremendous advantage.”

Check back Friday for part three of the three-part Cracking Appalachia’s Ethane Code series.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |