Regulatory | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Column: Mexico’s Pipeline Battle Signals Politics Trumping Economics

Editor’s Note: NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index, a leader tracking Mexico natural gas market reform, is offering the following column as part of a regular series on understanding this process, written by Eduardo Prud’homme.

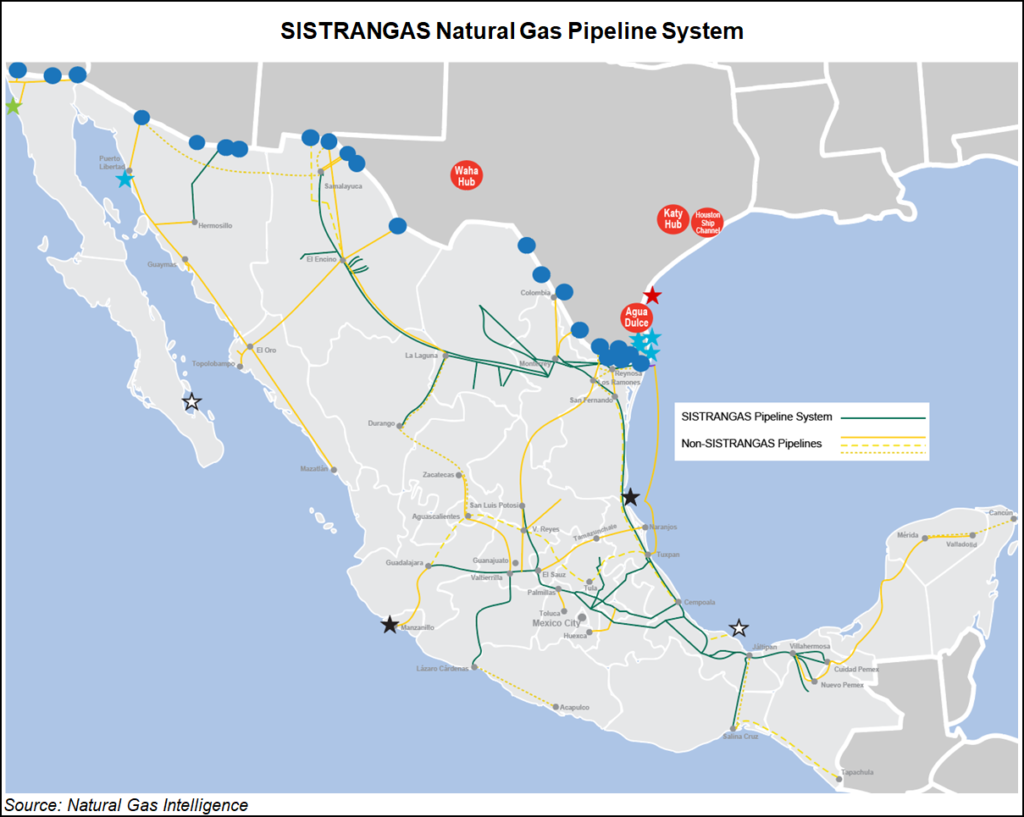

Prud’homme was central to the development of Cenagas, the nation’s natural gas pipeline operator, an entity formed in 2015 as part of the energy reform process. He began his career at national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), worked for 14 years at the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE), rising to be chief economist, and from July 2015 through February served as the ISO chief officer for Cenagas, where he oversaw the technical, commercial and economic management of the nascent Natural Gas Integrated System (Sistrangas).

The opinions and positions expressed by Prud’homme do not necessarily reflect the views of NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index.

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has repeatedly said his government seeks to separate economic power from political power. The narrative goes that corrupt “neoliberal” governments of the past slavishly handed over national resources to global capitalism without citizens receiving any benefit. To reverse this, the state must take on a leading role in the economy, so private investment cannot find space to influence politicians.

This vision is the framework of analysis to understand both the conflict and recent resolution to the contract dispute between various private pipeline companies and anchor customer Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE). Essentially, the government demonstrated through the spat that it will subject private enterprise to the guidelines that it establishes, and in doing so will distance itself from the way in which the private sector has interacted with the government since the 1990s.

The pipeline conflict was strange and damaging to Mexico, especially given the highly probable outcome of an unfavorable arbitration process for the CFE. The collateral costs of leaving thousands of kilometers of pipelines idle would have damaged the state utility’s balance sheet, not to mention Mexico’s growing demand for natural gas and falling domestic production.

But the conflict was never about economics.

Rigorous, competitive international public bidding processes were undertaken for the pipelines in question. Participants competed on an equal playing field. The winner won based on the rates it offered, with criteria clearly defined by energy regulator CRE. The participation of the companies in the processes was voluntary and transparent, and the proposed fees were accepted by the CFE.

Transport fees in natural gas transportation projects, whether negotiated, calculated for a tender or established by a regulator, are based on a projection of cash flow for the time period under evaluation. Said cash flow must be sufficient to cover the costs of construction, operation and maintenance of the service, along with taxes, depreciation of gas pipelines, compressors and other equipment, in addition to a reasonable return on investment.

The competitiveness of a bid depends on multiple considerations and expectations and implies significant efforts to simultaneously achieve operational and investment efficiency. Each participant has risks to face and has no way of guaranteeing ex ante that the projected costs will pan out as planned. One possible scenario is that the proposed cash flow is not sufficient to obtain the profitability that a board of directors requires for a project.

Today, the fact is that little can be done to change the nature of the seven contested natural gas pipeline projects. As of this year, construction was mostly finished, and few contractual and regulatory milestones were pending for the start of operations. The scale, configuration and capital intensity of the pipelines made it impossible to modify their actual costs. That is to say, from the perspective of the companies, to open a discussion on rates would change cash flow projections when many of the elements that explain costs had already occurred.

From the point of view of the private companies, CFE is an anchor client that makes an infrastructure project financially viable. CFE takes on market risk and absorbs certain risks in developing the project. The operational risks that remain throughout the life of the project and a large part of the costs derived from the occurrence of unforeseen events are risks to the developers.

Both parties take on risk, but do so under defined contract terms. When the contracts were drawn up, both parties sought to maximize their economic interest. Given this, calling the contracts “abusive” is a reckless act. With bidding rules that were public, it would be very difficult for the current CFE management to prove that the contract costs or clauses were not in line with the general practice of the industry.

The projects were awarded through a bidding process sanctioned by the CRE. The competitive nature provides the incentive for participants to do their best to win the process. To think that the companies competed and at the same time imposed convenient conditions is equivalent to imagining a case of collusion. In that case, CFE would have to prove that the different participants followed an anti-competitive strategic behavior, which would amount to a cartelization of the gas transportation sector.

If such were the case, there would need to be a formal investigation before the Federal Competition Commission. CFE management never suggested an investigation of this type.

The conflict is part of a broader change in Mexico in favor of parastatal companies. At CFE, the managers responsible for designing and executing tenders and signing the resulting contracts are no longer part of the company. Although there are legal mechanisms to ensure for continuity between governments, the dispute was a way of overriding this.

What the new government wants is that participants in projects accept the new rules and nuances in their relationships with the CFE. It seeks to show voters that the conditions achieved by the “market” were advantageous only to private companies. An exemplary and courageous act was necessary to prevent a national company from being affected by “abusive” contracts.

It’s no coincidence that the resolution of the conflict occurred weeks after Carlos Urzúa resigned as Finance minister. In his resignation, he openly stated that the director of the CFE was unaware of the concept of net present value, that the risks of interruptions in electricity supply in the Yucatán Peninsula were real and showed the weakness in the gas system, and that the complaints in the industrial sector because of the lack of gas supply were constant. He also said that this year the Mexican economy has simply not grown. A talented politician such as President López Obrador realized that perhaps he had stretched the rope too much and that it was time to build a bridge with natural gas transport companies.

On Aug. 27, the day an end to the standoff was announced, there seemed to be a turning point in the energy policy of the current government of Mexico. A turning point does not mean a change of direction, but a truce with a view to starting a new chapter in the relationship with investors in the energy sector. Although the new deal is heralded as including transparent rates in natural gas transportation, which reflect real costs and fixed over time, and balanced agreements on force majeure cases along with an end to any legal action, in the end the profit for the government is not economic but political. The message is that the negotiation was the result of the government’s determined and honest will to defend the interests of the people.

What’s important now is that the rules for a competitive market remain in place, such as open access, the optimization of capacity use, and the implementation of an explicit energy security policy based on the entry into operation of the new pipelines. This is not yet part of any public or media discussion.

If the main intention of this episode was to make clear the weight of policy in economic decisions, the government won. Private and foreign investors in Mexico will now add additional factors to the opportunity cost of capital. Politics in Mexico now dictates economics.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |