Regulatory | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

BOEM Financial Assurance Rules Align With ‘Realities of Industry’ as Operators Move to Deeper Waters

U.S. offshore operators face more stringent financial assurance and risk management requirements to ensure that they can pay to decommission and remove oil and natural gas production facilities, but critics say the changes could upend the industry.

The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) updated notice to lessees and operators [NTL No. 2008-N07] issued last week details improved procedures to determine an operator’s ability to carry out lease obligations. The directive replaces official updating procedures for financial security for oil and natural gas, or sulfur leases.

The obligations primarily involve decommissioning Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) facilities and whether a lessee should pay additional financial assurance.

“BOEM’s goal is to modernize its approach to risk management in a way that better aligns with the realities of the industry and protects the U.S. government and taxpayers from risk in a manner that isn’t overly burdensome to the oil and gas industry,” said BOEM Director Abigail Ross Hopper. “By implementing these changes, we will create comprehensive procedures to decrease risks to taxpayers, while providing industry flexibility to negotiate adaptive solutions and use tailored financial plans to meet their financial assurance requirements.”

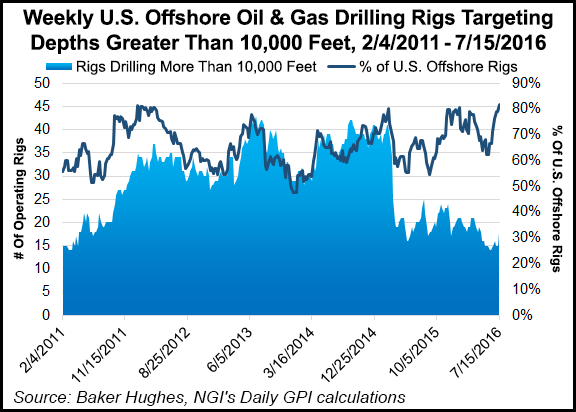

When an OCS lease is decommissioned, a company is required to remove all facilities and restore the site to its pre-lease state. Because industry has moved increasingly into the deepwater, “decommissioning costs have risen significantly. Moreover, as existing infrastructure ages, larger companies are transferring older facilities to smaller or less experienced companies.”

For routine decommissioning, current liabilities in the OCS are estimated at about $40 billion.

Updated criteria determine a lessee’s ability to self-insure OCS liabilities based on financial capacity and financial strength. Newly introduced are tailored plans, which would allow lessees some flexibility in securing financial assurance.

The guidance and clarification applies to all BOEM regions and planning areas. In addition to leaseholders, the NTL applies to right of use and easement holders.

“BOEM’s financial assurance regulations need to take into account current industry practices,” Hopper said. “We must ensure the U.S. taxpayer never pays to decommission an OCS facility and that the environment is protected. Managing risk in the early stages of a lease will provide lessees negotiated solutions that improve business certainty and leverage existing company strengths.”

BOEM said it would work with all lessees, both large and smaller individual lessees, to develop an approach that works best for the government and for each company, while focusing on the highest risk properties first, officials said.

“The intent is to examine each company individually, assess its total financial assurance needs and then work with the company to determine the best financial assurance instrument[s] for its individual needs.”

The NTL was published last Thursday (July 14), and BOEM is providing a 60-day grace period before implementation. The initial focus will be properties “that pose the highest risk to the government, namely, properties for which there is only one leaseholder responsible for decommissioning. Those leaseholders will have 60 days, from the date of an order requiring additional financial security, to comply.”

For all other holdings, lessees would have 120 days from the date they receive an order to provide additional security, if required. Alternatively, lessees may provide a tailored financial plan to comply with financial security rules other than through surety bonds and pledges of treasury securities.

“While BOEM has expressed a willingness to work with industry to ensure that the policy pronouncements of NTL 2016-N01 do not force any company off the OCS, the reality is that the reforms contemplated in BOEM’s new policy are very likely to change the profile of the U.S. offshore oil and gas industry,” said Van Ness Feldman LLP attorneys R. Scott Nuzman, Paul Korman and Jonathan Simon.

In a note, they said the reforms “ultimately could force some smaller operators to sell their assets to a larger company better positioned to meet the significant costs of supplemental bonding. This ultimately would lead to a consolidation of assets in the exploration and production (E&P) and pipeline sectors into the hands of a small number of large companies, signaling the end of the robust competitive market in the offshore oil and gas industry.”

In situations where a company is unable to find a willing buyer of its assets and unable to satisfy the requirements of a BOEM supplemental bonding order, federal officials also could issue civil penalties or request that Interior’s Bureau of Safety, Environment and Enforcement order the company to immediately decommission its assets, the attorneys said.

The financial assurance policy also could influence investment decisions by larger E&P companies, “ultimately leading those companies to conclude that the U.S. regulatory environment is far too burdensome to justify the billions of dollars in capital expenditure required to develop and produce resources in frontier areas such as the Arctic and ultra-deepwater Gulf of Mexico.”

Houston-based energy consulting firm Opportune said the updated rulemaking was an overreach that attempts to solve a “nonexistent problem.” A cost benefit analysis it conducted found the rules may financially harm many of the independent oil and gas operators working in the OCS.

“In a current period of depressed commodity prices and industry liquidity, BOEM could have used this opportunity to encourage future development of the OCS, while still protecting the U.S. taxpayer,” Opportune Partner Josh Sherman said. “The NTL has the potential to increase and accelerate risk to the U.S. taxpayer and Gulf Coast economy in a way unseen since the 2010 moratorium on offshore drilling.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |