Regulatory | Infrastructure | LNG Insight | NGI All News Access

As Railway Blockades Continue, BC Regulator Urges Diplomacy In Coastal GasLink Dispute

As disruption of Canadian freight and passenger trains by native rights and environmental protesters lengthens into a third week, TC Energy Corp. is embarking on a peace overture to foes of its Coastal GasLink (CGL) pipeline project across northern British Columbia.

The approval agency for CGL, the British Columbia (B.C.) Environmental Assessment Office (EAO), backs the diplomacy in a letter to the resistance faction leadership: avowed hereditary traditional chiefs of the Unist’ot’en or Dark House clan in the Wet’suwet’en tribe.

“The EAO strongly encourages Dark House to work with CGL,” says the agency’s letter to the dissenters from cooperation and benefits agreements that TC Energy has made with elected leaders of all tribes on the project route including the Wet’suwet’en.

“The EAO strongly encourages open and constructive dialogue between CGL and Dark House,” says the letter.

The diplomacy focuses on a camp lodge-like building that Dark House erected in the path of the project during about a decade of protest against all gas or oil projects in its claimed 22,000-square-kilometer (8,800-square-mile) territory.

The effort responds to a charge by the chiefs that the CGL approval is invalid because the firm and the EAO failed to consider effects on the structure as a native lifestyle revival temple that the clan calls its Healing Centre.

“The development of effective mitigation for protecting the objectives of the Healing Centre is best done with meaningful engagement between Dark House and CGL,” says the EAO letter to the tribal clansmen.

“It is important that Dark House engages with Coastal GasLink in discussing specific issues of concern and finds solutions to mitigate CGL’s impacts on Dark House’s economic benefits derived from the operations of the Healing Centre.”

The EAO letter to the natives and similar instructions to CGL grant both sides 30 days to file reports that can support a decision on potential amendments to the project approval.

CGL also is directed to file a thorough record of interactions with the clan chieftains. Any substantial engagement and communication would be a breakthrough for the pipeline project.

“Over the past month and over many years, we’ve reached out to the hereditary chiefs, over and over, but to no avail,” CGL president David Pfeiffer said Feb. 6 as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) enforced a Dec. 31 injunction against interference with construction. “It’s truly unfortunate.”

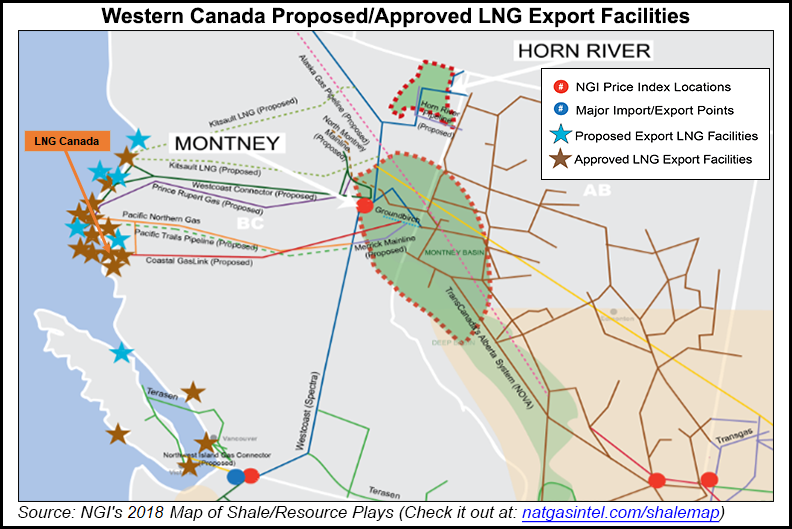

While work is on schedule on C$6.6 billion (US$5 billion) CGL as the supply line for the LNG Canada export terminal under construction on B.C.’s Pacific coast at Kitimat, the clan protest has escalated and moved east across the country.

Since Feb. 7 a Mohawk tribe within a half-day drive of Canada’s capital, Ottawa, has blocked a key Canadian National Railway (CN) mainline in eastern Ontario. Shorter-lived barricades have popped up in Quebec, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and B.C.

About 1,500 railway workers have been laid off due to halted freight and passenger train traffic. Industries from agriculture to manufacturing and retailing have appealed for the tracks to be cleared for recovery of national supply chains.

After discouraging police action to enforce court injunctions against the blockades by calling instead for “dialogue” for two weeks, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau responded to the appeals for action late Friday.

“The injunctions must be obeyed. The barricades must come down,” said Trudeau. “We cannot watch Canadians continue to suffer shortages and layoffs.”

But Trudeau announced no marching orders for the federal RCMP and said no military action is in the cards. He left injunction enforcement up to provincial police forces.

The northern B.C. protester clan leaders traveled to Ontario and Quebec to court Mohawk support, along the way rejecting truce overtures from Trudeau’s government. The train track barricades stayed up through the weekend.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |