Regulatory | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

As Mexico Preached Austerity, CFE Added 2,386 Workers in 2019

Mexico cut thousands of government energy jobs to reduce spending last year, but the state-run utility Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE) still added 2,386 employees, a sign experts say demonstrates the political sway of the electricity company’s CEO Manuel Bartlett, an ally of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

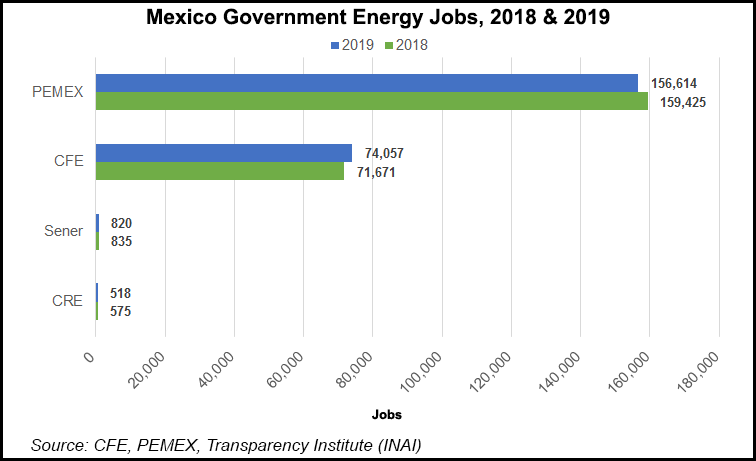

Since taking office in December 2018, López Obrador has repeated that government budget cuts and austerity measures will generate savings and stabilize the slowing Mexican economy. For the energy industry this has meant job reductions, as 2,988 total workers were laid off at six government entities last year. Layoffs were made at state oil producer Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex), the Mexican Energy Ministry (Sener), regulatory bodies Comisión Nacional de Hidrocarburos (CNH) and Comisión Reguladora de Energía (CRE), and energy agencies Cenace and Cenagas, according to data obtained by NGI’s Mexico GPI through public information requests.

The one government energy entity that grew, however, was the CFE, which added nearly 2,400 employees in 2019, expanding staff size to 74,057 from 71,671 in 2018, the company disclosed in response to an information request through the government transparency institute INAI. This anomaly, experts said, is indicative of both an inconsistent message from López Obrador and of the political clout of Bartlett.

“Remember that Octavio Romero Oropeza, Pemex CEO, and Manuel Bartlett, CFE’s CEO, are very close political allies of López Obrador, so the president has direct influence on how these state enterprises are run,” John B. McNeece III told NGI’s Mexico Daily. McNeese is senior fellow of Energy & Trade at the Center for US-Mexican Studies at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). “I view the increase at CFE as reflecting Bartlett’s plan to bring the electricity sector back under the full control of CFE with a substantially reduced role for private investors. With a larger role for CFE, they will need more people to carry that out.”

Pemex cut 2,811 jobs from the end of 2018 to the end of 2019, while CNH and CRE each reduced total staff by 10% last year, according to the information obtained by NGI’s Mexico GPI. These figures demonstrate López Obrador’s efforts to weaken energy regulators to give Pemex and CFE more autonomy, McNeece said.

“My view is that the administration wants to reduce the regulatory constraints on the state-owned enterprises Pemex and CFE and give them more scope to run their own show,” he said.

The energy industry has been rattled since López Obardor took office. His administration has vowed to rescue state energy producers Pemex and CFE while halting initiatives to attract foreign and private investment in the sector, which was the intent of the 2014 reform that ended government monopolies and opened the industry to new players. In just 16 months, the president has cancelled new upstream oil and natural gas auctions, renegotiated contract terms with private companies for natural gas pipeline projects signed during the previous administration and discontinued renewable energy tenders.

With less investment in the energy industry and more emphasis on government austerity, the increase in CFE job numbers conflict with López Obrador’s promise of reduced expenditures, experts say.

“The job cuts are indicative of the austerity that has taken place across the administration, with the one anomaly being the CFE,” IPD Latin America’s John Padilla, managing director, told NGI’s Mexico GPI. “It’s not because the CFE expanded its mandate. In many respects, you could argue that its mandate has actually shrunk. The platform was set up under the last administration to expand in natural gas. They are doing some of that, but certainly not at the size and scale they were looking at.”

Added Padilla, “These figures are indicative of the power Manuel Bartlett has as CEO.”

All four experts that reviewed the government energy job figures obtained by NGI’s Mexico GPI agreed that the increase in CFE staff could be explained by the weight Bartlett was given by the current administration. Bartlett has repeated that Mexico must reconsolidate power within the CFE, which he said was “butchered” by the previous administration as a result of the energy reform.

“If anyone could threaten the energy reform in a substantial way, it’s not López Obrador, it’s Bartlett,” Mexico energy expert Miriam Grunstein, chief energy counsel at Brilliant Energy Consulting, told NGI’s Mexico GPI. “If he wants more people, for example, he requests them and gets them. What we know is that Bartlett has a power of negotiation where he gets where he wants.”

She said under the López Obrador administration, the CFE has renewed authority in the industry. “You could say that CFE is the energy organization with the most political strength in the sector, given Bartlett’s relationship with the president.”

Talanza Energy Consulting’s Daniela Flores Ramírez, head of midstream and downstream in Mexico City, highlighted the incongruencies in the president’s message to the energy industry. From 2018-2020, CFE added a total of 1,902 jobs, while Pemex cut 3,286 workers.

“The numbers of CFE jobs gained and Pemex jobs lost have no consistency,” she told NGI’s Mexico GPI. “On one hand, you can talk about the austerity and the cuts that were made at the beginning of the administration, but that isn’t consistent with the increases at the CFE.”

Given the current global economic hardships as a result of the Covid-19 virus and plunging crude oil and natural gas prices, Mexico will likely need to employ more austerity measures in the energy industry this year. With Bartlett in charge of the CFE, however, that won’t necessarily mean a reduction in CFE employees, according to Grunstein.

“You can’t go looking for consistency or logic with López Obrador,” she said. “He goes on and on about austerity, while wasting money on things that aren’t needed.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |