E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

NC State Senator: Shale Bill Has Good Chance at Becoming Law

A bill that would lift North Carolina’s moratorium on hydraulic fracturing (fracking) and open the Tar Heel State to shale development has passed the state Senate and stands a good chance of being signed into law by Gov. Pat McCrory, according to one of the bill’s primary sponsors.

Meanwhile, Terry Engelder, a geosciences professor at Pennsylvania State University, said estimates by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) of how much gas and natural gas liquids (NGL) are locked in North Carolina’s shale basins are probably more accurate than previous estimates USGS made for the Marcellus Shale.

SB 786 passed a third and final reading in the Senate by a 35-12 vote on Thursday and now heads to the House of Representatives. Sen. Buck Newton (R-Wilson) told NGI’s Shale Daily that the bill, also known as the Energy Modernization Act, passed with bipartisan support in the Senate (see Shale Daily, May 21; May 16).

“I figure that the House will put its fingerprints on it, but the bulk of this bill, the vast majority of it, was worked up in the interim through our joint energy commission committee,” Newton said Thursday. “A lot of the leaders in the House that would handle this kind of legislation were involved in that process, and [there was] a lot of agreement before the bill was ever drafted. I’m hopeful that it will remain pretty largely intact and on to the governor.”

SB 786 would lift the moratorium on horizontal drilling and fracking on July 1, 2015 (see Shale Daily, March 4, 2013). It would also extend the deadline for the state to develop its own regulatory program; create a new Oil and Gas Commission and reconstitute the state’s Mining and Energy Commission (MEC).

“The MEC was the body created to put together the regulatory system, and they have put out for public comment the body of basic regulations that we charged them to come up with in order to get ready for this,” Newton said. “So they’re out there for public comment.

“The way we’ve set our timeline for rulemaking, all of those rules essentially should be in place and completed and in effect by July 1, 2015. We wanted to go ahead and get that signal cleared up to industry that we will lift it, and that they’ll be ready to start requesting permits, hopefully as early as July or August of 2015, if they’ve found a reason to.”

The bill would also invalidate local bans on oil and gas activities, ban wastewater injection wells and establish a severance tax.

“Our geology is not appropriate for injection wells,” Newton said of the ban. “That was something we looked at in the past, and as we learned more we decided that that’s just not the way we need to be handling it here.”

On local bans on oil and gas activities, Newton said, “we’re trying to make sure there’s not a patchwork of local regulations and local obstacles and difficulties for the industry. We want to make sure that they have basically as much as possible a kind of a one-stop shop, and they can very easily see what the landscape is, what they’re required to do and who they need to answer to. We thought that was important, to have a statewide approach to that.”

Newtown added that MEC would require industry participation in FracFocus, the frack chemicals registry launched in 2011 by the Groundwater Protection Council and the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission (see Shale Daily, April 6, 2011).

“We also require companies that claim that their recipe is a trade secret to disclose that to our state geologist,” Newton said. “[The geologist] would certify that there’s no banned substance in there, but they would hold it. In the event there was any kind of public health emergency, then it would be available to be disclosed to responders and healthcare providers.

“I know that’s been an issue around the country, but that’s how we’ve decided to deal with it. The trade secret side of it is always touchy. How do you give comfort to the public to know that there’s not something out there that nobody knows about, but at the same we’re protecting the industry’s concerns for being competitive?

“I think all the stakeholders from industry and most of the serious health folks are satisfied. We’ll see. Some folks will never be satisfied.”

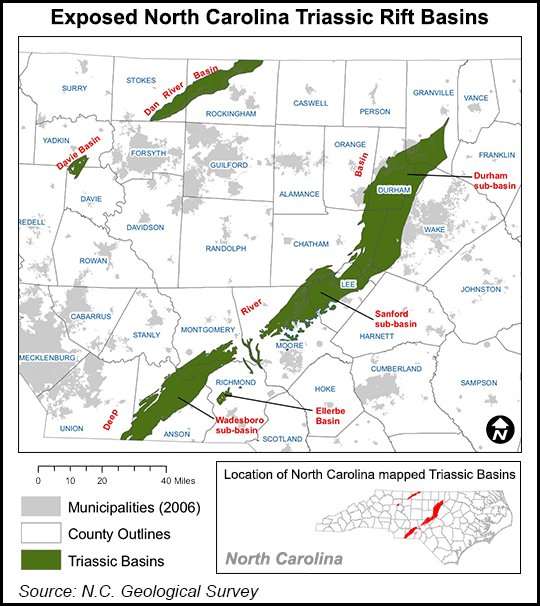

According to the North Carolina Geological Survey (NCGS), the Deep River Basin is a 150-mile half-graben that traverses most of the central part of the state in a southwest-to-northeast direction. The basin is divided into three sub-basins — from north to south, the Durham, Sanford and Wadesboro sub-basins — each of which include about 7,000 feet of Triassic strata.

The strata found in the Deep River Basin, according to NCGS, are divided into three formations. In descending stratigraphic order, these are the:

NCGS added that the Cumnock Formation includes an interval of Upper Triassic (Carnian) organic-rich black shale, measuring about 800 feet in thickness. The shale covers about 25,000 acres at depths of less than 3,000 feet in the Sanford sub-basin, in Lee and Chatham counties.

In 2012, the USGS estimated that there was a 95% chance the Deep River Basin held 779 Bcf of natural gas and 35 million bbl of NGLs, both of which were classified as undiscovered resources (see Shale Daily, June 21, 2012). USGS added there was a 50% chance the basin held 1.53 Tcf of gas and 75 million bbl of NGLs, and a 5% chance for 2.99 Tcf of gas and 158 million bbl of NGLs.

The mean averages of the USGS estimates are 1.66 Tcf of gas and 83 million bbl of NGLs.

In 2002, USGS estimated the Marcellus held about 2 Tcf of gas and 10 million bbl of NGLs. Nine years later, those numbers were updated to 84 Tcf of gas and 3.4 billion bbl of NGLs (see Shale Daily, Aug. 29, 2011; Aug 24, 2011). But Engelder cautioned that USGS may not have made the same mistake in North Carolina.

“There is a very large difference, on a number of levels, between the geology of the Marcellus and that of the North Carolina basins,” Engelder told NGI’s Shale Daily on Friday. “Probably the most important is that those basins tend to be sourced with lacustrine source rocks. The Marcellus, on the other hand, is marine.

“The two types of deposits have been tested in enough places globally right now that it appears that lacustrine deposits have not had quite the magnificent results that marine deposits have had. And so with that, the USGS estimate is probably closer to the real deal.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |