Shale Daily | NGI All News Access

Oil Supply Doesn’t Hinge on Rigs, Decline Rates, Says Raymond James

The domestic oil rig count will continue dropping at a modest rate on pad drilling and technological advances, but there’s no doubt that U.S. oil supplies will surge regardless, said analysts at Raymond James & Co. Inc.

J. Marshall Adkins and John Freeman said in a note to clients on Monday there is a “growing misconception” that production might collapse in several plays because of the high decline rates, which in turn would snap the oil renaissance underway. The theory is, more drilling would be required to maintain the growth in oil supplies to offset declines from existing wells.

“This simply is not factually correct,” said the duo.

Yes, unconventional wells have high rates of initial declines but production flattens relatively quickly. As soon as there is a solid foundation of wells that are three to four years old, a stable base of production continues, they said.

While this is may not satisfy all critics, Adkins and Freeman conducted a case study to project Bakken Shale oil output using current industry-reported type curves under different rig count scenarios.

Fears of high shale decline curves halting or reversing output are “overblown,” they said. “Rather, we are somewhere in the middle…We do believe we will continue to see substantial U.S. oil supply growth even as rig counts continue to fall. We are already seeing it happen.”

In the Barnett, Eagle Ford and Bakken shales, production hasn’t rolled over. In the Eagle Ford and Bakken, it hasn’t slowed despite rig counts falling for the past two years. Not included in the analysis were issues that could impact expansion down the road, such as water disposal capacity and declining formation quality. Those variables would moderate growth “but we do not expect it to be the screeching halt before falling off a cliff as postulated by some.”

The Bakken was used as the test play because the analysts believe it is representative of others.

“From the start of 2007 through the end of 2013, Bakken oil production increased from 132,000 boe/d to just over 1 million boe/d,” a compound annual growth rate of 40%, based on Energy Information Administration (EIA) data. In two periods, the Bakken had falling rig counts: the first half of 2009 and all of 2012 and 2013. At no time was there a noticeable slowdown in production, said the analysts.

“On the contrary, just based on eyeballing the chart, production could even have accelerated over the latter timeframe.” Initial decline rates are huge — 70% in Year One, but by the third and fourth year, rates moderated to 15-20%. Using a 30-day initial production rate of 500 boe/d, Raymond James’ type curve results in an estimated ultimate recovery of just under 500,000 boe.

The latest rig count in the Bakken was 174 rigs, based on recent EIA data. That’s almost 20% below the all-time high of 218 rigs in June 2012. If the rig count were to stay flat, production would not roll over.

“Rather, our model shows that production would exceed 1.6 million boe/d by 2021 — and that is under the generous assumption that the existing production base will decline by 35% in the first year.”

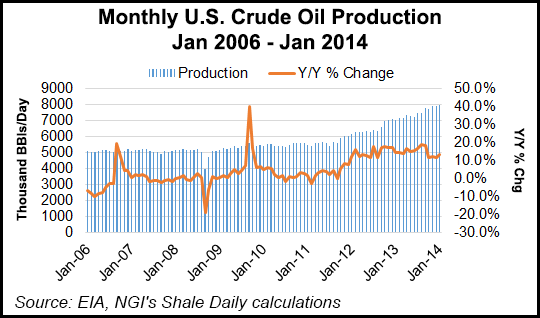

Total U.S. crude oil production, which had remained between 4.90 million b/d and 5.60 million b/d for several years, has been on the rise since late 2011, reaching 7.94 million b/d in December, according to Energy Information Administration data.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |